As the Lion Bit Down, the Man Felt Sure He Was About to Die

A classic Drama in Real Life from the Reader's Digest archives, originally published in 1977.

The 18-month-old lion cub, already bigger than a Great Dane, leaped out of the thick underbrush, put his furry front paws up on Tony Fitzjohn’s broad shoulders and rubbed heads joyously with his friend. It was Thursday, June 12, 1975, and in lion fashion Freddie was welcoming Tony back to Kora Camp after a two-day supply trip.

Kora, an isolated huddle of tents protected by a high wire fence in northern Kenya, was where 70-year-old naturalist George Adamson rehabilitated lions in a unique conservation project. Orphaned cubs or young zoo lions—animals that would otherwise remain in captivity— grew up, reproduced and lived free in an area the Kenyan government had designated as a national game reserve.

Conditions at the camp were rugged: intense heat and biting tse-tse flies, no electricity or plumbing and a six-hour drive to the nearest settlement. But English-born Fitzjohn, 31, had read the Born Free books as a teenager and been captivated by the story of Joy and George Adamson raising the orphaned lioness, Elsa. Living in Africa and working with Adamson for the last three years had been a dream come true for Tony.

One of his regular jobs was a monthly trip by Land Rover to buy supplies at the tiny outpost of Garissa. This morning, before his return, he had stopped to see the district game warden and thank him for evicting a gang of armed poachers who had been leaving poison traps for rhinos inside the reserve.

The warden had asked about Freddie, the abandoned lion cub he had found in the bush some 17 months earlier and turned over to Tony. It was the first cub Tony had known. He’d taken the frail, fluffy animal in his arms, driven him home to Kora and named him Freddie.

Later, three more cubs were brought from zoos. But Freddie always held a special place with Tony. Freddie was not only good-natured, but also the bravest of the cubs, scrappier and more inclined to take liberties with the fully grown wild lions that prowled around the fence. He and Tony had slept in the same bed until Freddie outgrew it. Tony’s girlfriend, Lindsay Bell, who was living in Nairobi, had noticed that he was completely relaxed only when he was with his lions.

After two days of rough driving, Tony was exhausted and glad to be back at Kora. He was dressed only in shorts and sandals, his tan skin glistening with perspiration in the 36-degree heat. It was 5:10 p.m., time to gather the cubs—the other three had joined Freddie now in welcoming Tony—and take them inside the fence for the night. To settle the frisky Freddie, Tony sat down, his back to the underbrush a few metres away, and began talking quietly. Though a rule in the bush is never to sit on the ground outside camp—because of the possibility of unexpected contact with animals—Tony felt safe just 50 metres from camp.

Without warning, he felt a giant creature pounce on him from behind. He crashed forward to the ground and momentarily lost consciousness. When he came to, it was to the terrifying awareness that his head was locked in the jaws of an enormous lion.

The attacker clamped down hard, then released the headlock and began a barrage of biting and clawing—sharp bites to the neck and head, deep bites to both shoulders, slashing claws to back and legs.

To Tony this horror was a series of jerky slides punctuated by blackouts. His glasses were smashed and he saw ashes of the camp he had thought close; it seemed to be moving farther and farther away, getting smaller and smaller. Which lion was attacking him? One of George’s? He only knew that the beast was fully grown and powerful.

Tony covered his genitals and closed his eyes. More blows from mighty paws struck his head; more deep gashes from razor-sharp claws opened his face. Because of shock and concussion, he felt no pain and heard no sounds. Paralyzed by injuries and bewilderment, he was experiencing his own death as a silent movie.

Now the lion grabbed Tony’s neck and bit down. Tony remembered that lions often kill by strangulation, holding their vise-like grip until the prey stops breathing. It takes no more than a minute.

Then he realized that there were two lions in the battle. As he forced his bloody eyelids open, he saw Freddie charging toward him. Oh, no, not Freddie, too! he thought.

But Freddie wasn’t attacking Tony; he was after the mighty lion, four times as big as he. Proper juvenile behaviour is to submit to adult lions. To attack an enraged adult was suicide.

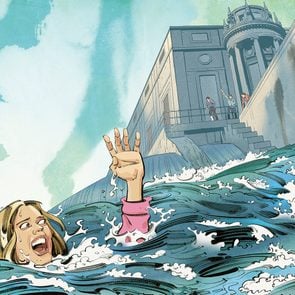

Freddie, however, snarled and bit at the flanks of the lion that stood astride Tony’s torso. For an instant it worked. The lion released his grip on Tony’s neck and charged after Freddie, who ran for his life.

Tony lay in a pool of blood, gasping for air. The attacker could have torn Freddie apart on the spot, but he stopped his pursuit and ran back to the victim. Again, he clamped down on Tony’s neck. God, I’m dying! I can feel it, Tony thought, then lost consciousness again.

But Freddie returned to the fray and bit the surprised beast’s rear, then circled while making snarls and yelps, bold charges and nips. Freddie withdrew only when the bigger animal swiped at him with his powerful paw. Throughout the attack, Tony was a silent victim and the lion a silent killer. The only sounds were Freddie’s unrelenting growls and piercing yelps that Tony could not hear.

Freddie’s shrill cries were heard by Erigumsa, the compound’s cook. At first, he thought two cubs were fighting, but Freddie’s distant voice sounded too desperate. The cook ran to the gate and saw Tony being mauled. Erigumsa raced to the dining tent, 25 metres away, where Adamson was having tea.

“Simba ame kamata Tony inje! Anataka kuua yeye!” he cried in Swahili. (“The lion has caught Tony outside! He’s trying to kill him!”)

George assumed the cubs’ playfulness had gotten too rough. So when he ran from the tent he took only a walking stick, bypassing a loaded rifle.

But outside the gate, George saw Tony’s neck locked between the jaws of a full-grown lion. There was no time to return for the rifle. Without a second thought, he charged the lion, yelling and waving the walking stick.

Now George was vulnerable to attack. The beast released Tony and retreated, staring at George. The lion prepared to spring, but George kept moving forward, shouting and brandishing the stick. It worked! The lion hesitated, then slunk off into the bush, splotched with Tony’s blood.

The next thing Tony knew, he was stumbling back to camp, supported by George. “George, I think I’m dying. Whatever you do,” he pleaded, “don’t shoot the lion. My fault … Caught unaware … Shouldn’t have happened.”

The minute he got Tony into his tent, George rushed to the shortwave radio to call the Flying Doctor Service in Nairobi. It was too late—the 210-kilometre flight would take an hour and a quarter, and regulations firmly prohibit landing on a bush strip after dark, even for a critical emergency.

The nurse assured George that the plane would come first thing in the morning and advised him on first-aid treatment for Tony’s many deep wounds.

George signed off, staring at the setting sun. Could Tony make it through the long night ahead without a surgeon and blood transfusions?

Drifting in and out of consciousness, Tony fought for breath—and life. I’ve got to live—for Lindsay, George and the lions. I know if I just think about living, I’ll make it.

At dawn, George and Erigumsa managed smiles; 13 hours after his mauling, Tony was still alive.

Lindsay was the first one out of the Flying Doctor aircraft when it touched down—George had radioed her the night before. “I was expecting bad wounds, but not all over his head,” she recalls. “He could hardly breathe. The right side of his neck was open and his wounds were oozing. It was horrible.”

During the flight back to Nairobi with Tony, Lindsay broke down and wept. “I knew how much he loved his work,” she says. “If he lived, would he ever want to return to the lions?”

Tony spent two hours in surgery when they got him to the hospital. There were three dozen wounds—some so deep and dangerous they couldn’t be stitched at that time. His trachea had been squeezed but not broken. Miraculously, the lion’s teeth had not severed any nerve, artery or vein. Tony would be one of the few people ever to survive a lion-mauling.

The day after the attack, a large lion appeared outside Kora with dried blood on his chest and muzzle. It was a 30-month-old wild animal George had known since infancy, a creature so placid that he’d been named Shyman.

Now Shyman was growling menacingly at the cubs. George drove outside the compound and positioned the Land Rover between Shyman and the frightened cubs. Then he observed Shyman carefully. His movements were erratic, unusual.

The once-gentle lion had probably eaten from a poisoned carcass left by the rhino poachers. Since he had attacked once, he could do it again. The lives of humans and other lions were in jeopardy. After an hour of watching Shyman, George sadly raised his rifle and shot the lion dead.

Such a mauling as Tony had received would make even the bravest soul re-evaluate the risks of work in the bush. The scars on his face and neck would be with him always. But Tony remembered how a lion cub whom he loved had tried to save him.

Two months after the accident, Tony returned to Kora, wondering what kind of greeting he’d receive after his absence. When the cubs saw Tony, they rushed toward him, Freddie in the lead, making woofing sounds all the way. Typical lion greetings last less than a minute; this one lasted close to 10 minutes as the excited cubs leaped all over Tony.

“I never had any thoughts about not going back,” Tony said later. “We’re creating an animal reserve. People from all over the world can eventually come and see our lions, and the lions can live free and unmolested in nature. I belong here.”

Tony Fitzjohn continued to work at Kora until 1989, when he moved to Tanzania to lead efforts to rehabilitate a national park that had been decimated by farmers and poachers. Elephants are once again flourishing in the area, and Fitzjohn also helped bring rhinos back to Tanzania. In 2006 he was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his conservation work.

In 2020, he returned to Kenya with his son Alexander to restore Kora, which had fallen into neglect after George Adamson’s death in 1989. “Everything that I am today, I owe to Kora,” Tony told Gentleman’s Journal in 2021.

Tony Fitzjohn died in May 2022 of a brain tumour at the age of 76.

Next, read this chilling story of a rogue bear attack at Liard Hot Springs.