To Get Help, This Man Had To Leave His Kids on a Cliff. He Prayed They Would Survive

God asks us to forgive others, but if you’re responsible for your children’s demise, how do you ever forgive yourself?

Lost on Burke Mountain

Brandon Hoogstra had hiked Burke Mountain, near his home in Coquitlam, B.C., once before. He knew the route to the summit and an abandoned ski lodge.

But he and his wife, Claire, objected when their two eldest, six-year-old Ezri and seven-year-old Oliver, begged to join him for another hike in May 2019. The route was too long—at least 11 kilometres. Even if the weather was nice, they’d surely get tired. And while she loved her husband dearly, Claire worried about him—Brandon is on the autism spectrum, socially awkward at times, highly sensitive and prone to choices that might seem erratic.

The Hoogstras were new to town. Thirty-five-year-old Claire and 34-year-old Brandon had both grown up in the Atlanta area. Wanting to experience life outside the U.S., they’d lived for a couple of years in Chiapas, Mexico, where Brandon worked at a water-treatment plant. In 2018, they decided to give Canada a try, and rented a basement suite in Coquitlam for themselves and their four kids (Gabriel was 22 months, Holly six months).

Ezri and Oliver were so keen to climb the mountain that the parents finally relented. Just after 8 a.m. on a beautiful Sunday morning, they set off. Brandon’s backpack held his phone, Clif bars, packets of apple sauce, apples, water bottles and fishing gear. They’d refill the bottles in the clear streams up the mountain.

Brandon had planned a varied route up the mountain. The winding ascent was fun and uneventful. Near the top, thick snow blanketed the trail. Excitedly, the kids raced across the crusted surface.

At the summit, Oliver and Ezri shared the second-last Clif bar while Brandon looked around. His phone showed 1:30 p.m. and no reception. They’d rest for an hour, he decided, then head back to Claire and the babies.

When the kids started down the far side of the slope, Brandon said, “You guys really want to find those fishing lakes, don’t you?” He’d identified them on Google Earth.

“Oh, yes!” Ezri said.

So they took an unfamiliar route down the other side of the mountain.

By the time Brandon realized the path they were on had become an animal trail alongside a stream, it made sense to keep following it. When the stream reached a cascading waterfall, they clambered carefully down the slippery rocks to the pool below.

The stream sang to them, and they kept following it down. The day had been bright and beautiful. Mid afternoon, when the sun disappeared behind heavy grey clouds, they suddenly felt disoriented, cold and hungry. Brandon tried to light a fire, but couldn’t ignite the wet twigs.

They decided to continue hiking down. For half an hour they cautiously descended until they reached a sheer cliff edge. The stream became a noisy, six-metre waterfall. Brandon cursed himself for taking an unknown route down. He hadn’t studied this area and he didn’t have a map. Ezri took his hand. She, like Brandon, had a unique way of processing the world. “Dad,” she said, crying, “I love you, and I don’t blame you for getting lost. You’re my dad, and you’re nice.”

“Babies,” he said, “hopefully there are no more waterfalls. The Lord will guide us.”

They held hands as they carefully descended. Finally, Brandon said, “It’s too steep. We’ll have to slide on our butts.”

Still holding hands, they inched down the slope. Tree trunks were rest stops. Fir saplings, their roots sunk deep in the rock, made handholds. It worked well until they reached a sheer, 10-metre drop and the stream became a deafening waterfall. Mist soaked them as the water raced over a tumble of boulders.

“Easy-peasy,” Brandon said, like a character from the kids’ favourite movie, Horton Hears a Who. They made their way, inch by inch, until Oliver slid on a loose rock and all three of them went flying.

Mid-air, as if in slow motion, Brandon watched his son’s head smack a boulder. Then his own head hit rock. Stunned, ears ringing, he realized he’d split open his forehead.

“Help me, Dad!”

Oliver, in the water, was being swept away. Brandon desperately lunged and pulled him to safety. One of Oliver’s shoes floated off.

Brandon wiped blood from his eyes and gathered his senses. Was anyone hurt? Oliver, crying and shivering, seemed okay. Ezri was wailing, but she too appeared uninjured. Brandon himself, though disoriented, didn’t feel anything worse than the gash on his forehead. The backpack was lodged in the rocks six metres away. He saw no use trying to retrieve it.

After calming the kids, he said, “Stay here while I look for a way out. I’ll be right back.” As he worked his way downstream, the terrain became less steep. It seemed they were through the worst of it. He climbed back up to the kids to share the good news.

“I’m missing a shoe, too,” Ezri said.

“Honeybunch,” said Brandon, “if you guys can’t have both shoes, I don’t need mine either.” He pulled off his shoes and threw them as far as he could.

On they went. The slope was gentler at first, but when they emerged onto a gravelly plateau near a 30-metre waterfall, their plight was suddenly, painfully clear. The air was cold and getting colder. They were wet and exhausted. Brandon had no idea where they were.

This plateau was a safe spot. To save the kids, Brandon realized, he had to go for help.

“Oliver, Ezri,” he said, taking off his grey hoodie and draping it around them, “stay here, no matter what. Do you understand? I’m going to get friendly people who’ll pull you out. They’ll come in a helicopter.” He kissed each of them on the forehead. “I love you. Stay right here.”

“We will.”

Brandon gazed down the gnarly cliff face. Before starting his descent, he didn’t look back. He didn’t want that mental picture, in case it was the last time he saw his kids alive.

Brandon managed to bushwhack a few kilometres down to the base of the mountain, suffering another bad fall on the way. Fortunately, he’d landed on his back in a dense bed of ferns.

Exhausted and bloodied, bare feet in shreds, he emerged from the forest and bumped into a family of hikers. They called 911.

“Your kids will be okay,” the father assured him. “Let’s say a prayer together.”

Around 4 p.m. that afternoon, at home in Coquitlam, Claire felt a weird sensation. Brandon had said they’d be home by nightfall. It was still hours away, but something didn’t feel right. She went to phone him but couldn’t find her cell, and then the babies needed attention.

Around 5 p.m. her phone rang. Relieved, she imagined it was Brandon, calling to say when they’d be back.

It was a dispatcher from Coquitlam Search and Rescue. “Mrs. Hoogstra? I’m sorry to tell you that your husband and children took a bit of a fall.”

“Oh my gosh. Are they hurt?”

“Your husband hit his head, but he said the children are alive. We’re going to pull them out with a helicopter. That’s all we know so far. I’ll keep you updated as I get more information.”

Around 8 p.m. the dispatcher called Claire again. “Your husband’s at Eagle Ridge Hospital,” he told her. “He hit his head, but appears to be okay.”

“Oh, thank goodness.”

“We are having trouble locating your children.”

“What?” Claire gripped the counter. “Aren’t they with him?”

“He made his way out, but he had to leave them behind.”

For a moment, she couldn’t speak.

“Ma’am? Are you still there?”

Claire focused on her breathing. “I’m here. I’m not going to pass out. But I can’t lose my children.”

An hour later, when two RCMP officers knocked at the door, her stomach dropped. Dear God. Her father had been in law enforcement. He said the worst part was informing a parent of their child’s death.

Mercifully, the officers only needed more information.

Around midnight, the RCMP brought Brandon home for fresh clothes. He’d been stitched up, given a tetanus shot and checked for internal injuries. Claire understood the fragile emotional state he’d be in.

“Honey,” he said, trying not to weep, “I’m sooo sorry about what I did to the kids…”

“No, you were just taking them on a hike,” she soothed. “They’re coming home, I promise. Now go and help find them.”

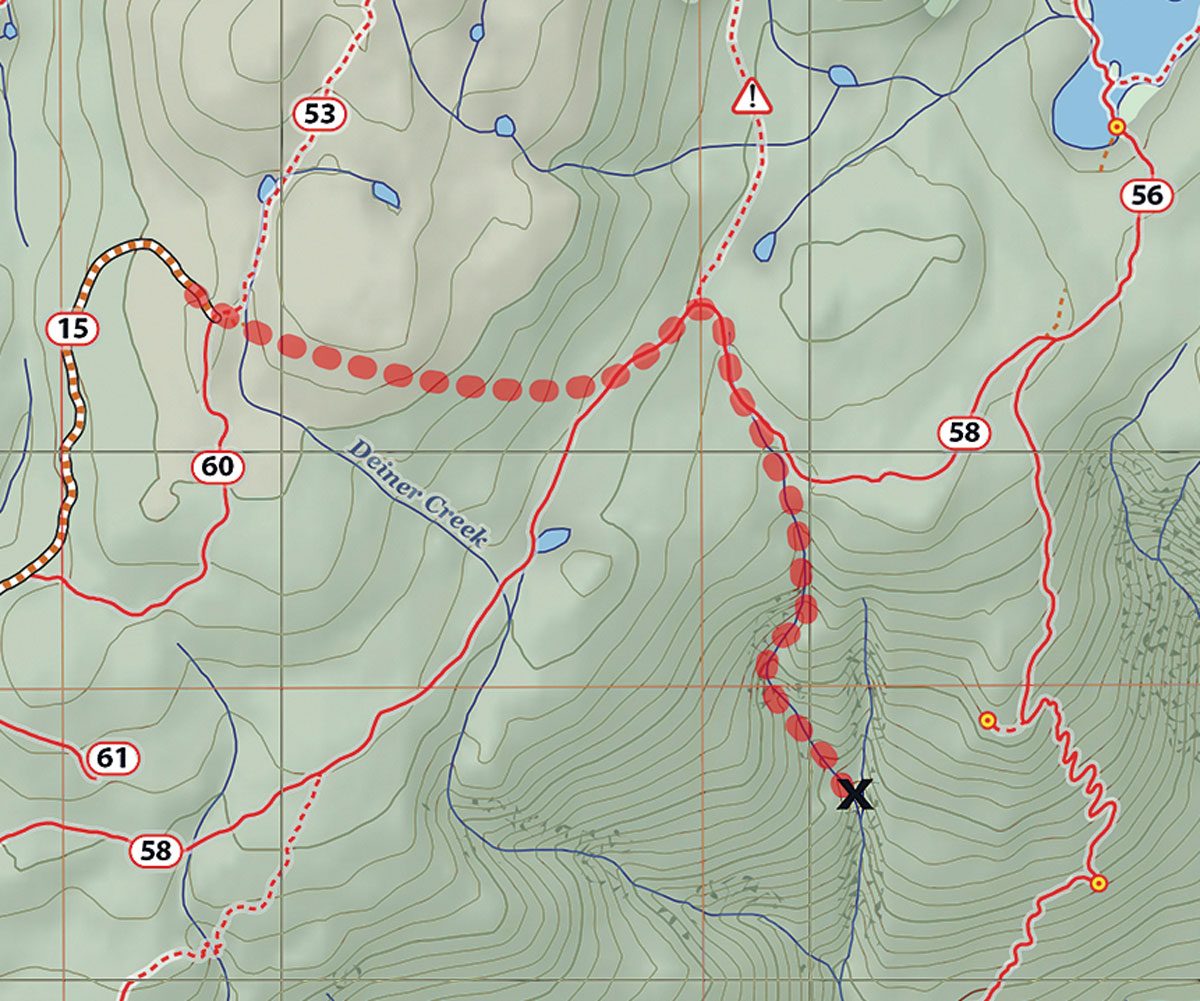

Al Hurley and Bill Papove, two veteran volunteers with Coquitlam Search and Rescue, had been dropped off by a helicopter part way up the mountain, just before darkness fell. Details were still scarce. They only knew two young children were stranded in Class 5 terrain—the most difficult.

The two men, wearing 18-kilogram emergency packs, spent all night zigzagging down the treacherous terrain. GPS recorded their route as they searched for signs indicating which of the drainages Brandon and the kids had been descending.

At 4:30 a.m. Hurley and Papove, in need of food and rest, met another SAR team on the mountain to hand off information. Then, the two men hiked down to base camp—a mobile home equipped with live satellite images and a topographical map. Brandon helped trace their route as best he could. When the teams set off again, he began to cry. Soon he was bawling in agony. As a parent, he knew he had one job: protect your children. God asks us to forgive others, but if you’re responsible for your children’s demise, how do you ever forgive yourself?

RCMP constable Morgan Nevison introduced himself. Though Nevison had not been specifically trained in emotional support, he had a gift for it. He’d served in the military, and Brandon’s dad had fought in Vietnam and developed PTSD. The two men were soon chatting like old friends.

“You know,” said Nevison, “a buddy, he got lost in these woods a few years back. He was missing for three days before they called it off. As they were preparing to leave, he knocked on that door right there.”

Just then, SAR volunteer Jim Mancell stopped in with good news: searchers had spotted a blue shoe.

Nevison, with his easy manner, kept Brandon engaged until Jim returned.

“We’ve got voice confirmation. I’ll keep you posted.”

Please God, let them be unharmed.

Finally, 20 minutes later, Jim came back inside: “Great news. We’re with your kids.”

Brandon leapt up, laughing and crying. When Nevison drove him to an open field, he was moved to see so many strangers in bright red SAR jackets.

Soon the thwack-thwack-thwack of rotors announced the arrival of the helicopter. Oliver was dangling from a long line, between Al Hurley and another volunteer. Brandon ran to embrace his son. Before long the helicopter returned with little Ezri on the line. The kids were rushed to Royal Columbian Hospital, in New Westminster, to check for injuries and hypothermia.

It turned out they were fine, just cold and hungry. After Brandon left the children had talked a bit. Just before dark they heard a helicopter. They were so exhausted they soon fell asleep, huddled together for warmth. The kids kept their word and didn’t move from their spot all night. “They had very little trauma afterwards,” Claire explained later. “They both felt that Brandon had been truthful about their rescue and it was just a matter of waiting for a helicopter.”

Of the hundreds of rescues he’s participated in, Al Hurley found this one among the most satisfying. “Many of us are parents,” he explained. “When you hear the words ‘injured,’ ‘child’ and ‘wilderness,’ it gets intense. This one had a happy ending. That’s not always the case.”

Two months after the rescue, in July 2019, the Hoogstras moved to Washington State, across the border from B.C. Oliver and Ezri still love hiking with their dad, though they prefer to stick to shorter routes now. They remember huddling together that cold night on Burke Mountain, of course, but otherwise the brother and sister seem untroubled.

Brandon is a different story. Having quit smoking while the family lived in Canada, he started up again to soothe his nerves. He paints. Flashbacks overwhelm him. In tears, he takes solitary walks in the forest.

Before the Hoogstras left Coquitlam, a volunteer dropped by to return their recovered items—a backpack, fishing gear, some shoes. One search manager called them “a trail of bread crumbs” that helped to lead the rescuers to the children.

In the backpack, someone had placed a bright red jacket with a patch that reads Ridge Meadows Search and Rescue. The jacket reminds the Hoogstras of everyone who risked their safety to help people they didn’t know. When Brandon is overcome by guilt, or anxiety, or sadness, he takes out the red jacket.

Putting it on helps him remember he’s not alone—there’s always someone out there who is willing to help.

Next, check out our collection of the most gripping survival stories.