Uncovering the Lost Story of a WWI Soldier

A visit to the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier inspired this Edmonton man to learn as much as he could about a long-lost relative.

During the summer of 2017, I paid a visit to our nation’s capital of Ottawa and saw both the National War Memorial and the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. This brought to mind a small, worn-out, pocket-sized New Testament that my mother gave to me many years ago. She told me it was a prized possession of her father, my grandpa, Thomas Watson, as it belonged to his brother who went missing in World War One and was never heard from again. At the time, and to my discredit, I possessed no interest in a man who paid the ultimate price for our freedom, despite having served in the Canadian Armed Forces Reserves myself. I had other interests and did not try to find out more about this relative. From time to time, I would look at the New Testament and wonder who this long-lost relative was and what he went through but took it no further. Looking at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, I finally decided that if I was going to talk the talk about remembering our living veterans, and honouring those who fell defending our country, I had better find out more about this man who paid the ultimate price.

My Remembrance Day project kicked off in September 2017, but I had very little to go on at first. I didn’t know where my long-lost relative served in World War One, which army unit he served with, when he fell in battle or even his name.

I decided to gather as much information from the resources that I had. Those included Google searches, Wikipedia, Canadian Veterans Affairs, a collection of memorabilia owned by my cousin, Dr. Richard Haugen, and picking the brain of my oldest living relative, my 89-year-old aunt, Francis (Betty) Haugen. Thankfully, I can now paint a pretty clear picture of the short life and service my long-lost relative—Private George William Watson—lived.

George was one of six children of my great-grandfather, Thomas Oats Watson, and was born on January 18, 1883. He was raised in a deeply devout family of Methodists in Arden, Manitoba, and remained very religious to the end of his life. In the letters he wrote to his youngest brother, my grandfather Thomas Watson, it is clear he was interested in horses, farming, local politics and even automobiles. My aunt Betty informed me that George most likely could have avoided military service, and lived to a very old age, but chose to come to his country’s aid in its hour of need.

Military Service History

From the Canadian Virtual War Memorial, I found George’s Attestation Paper, which was filled out when he enlisted on June 10, 1916, in the 200th Battalion CEF (Canadian Expeditionary Force) of the Canadian Army. His battalion was formed and based in Winnipeg and began recruiting during the winter of 1915-16. George Watson would remain in the 200th Battalion CEF during his military service and training while still in Canada.

I now turned to a series of letters that Private Watson wrote to his youngest brother, Thomas Watson, in an attempt to discover more clues, and piece together George’s training and postings in the Canadian Army.

In an undated fragment of a letter, George mentioned that he received a letter from his mother, which she had sent to Camp Aldershot with some Sunday school papers, while he was aboard ship in the Halifax harbour. George also makes mention of how military drills were conducted differently than Camp Hughes. It can therefore be safely assumed that Private George Watson was assigned to Camp Hughes and Camp Aldershot before shipping out from Halifax.

I quickly turned my attention online, to a website run by Parks Canada. I learned that Camp Hughes, named after Sir Sam Hughes, Canada’s Minister of Militia and Defence (1911-1916), was a major training area for the Canadian Army during World War One. In 1916, the year George Watson joined the army, Camp Hughes reached its maximum size—a total of 27,754 troops undergoing training. This made Camp Hughes, at the time, the most densely populated area in Manitoba, outside of Winnipeg. In order to train soldiers how to operate on a battlefield, Camp Hughes featured an extensive trench system, which is still there today for visitors to see. Despite the camp’s closure in 1934, it is still recognized as a place of national historic significance by the government of Canada.

As I continued my search on Wikipedia, I learned that Camp Aldershot, located near Kentville, Nova Scotia, was a training centre for the Canadian infantry during the First World War. More than 7,000 soldiers at any particular time were undergoing training there. While there were temporary buildings to house cooking faculties, mess halls and the camp hospital, the men undergoing training at that camp lived in tents. Odds were George went through basic and infantry training at Camp Hughes, Camp Aldershot, or both, before being shipped overseas. At 33 years old, George would have been older than most recruits, especially since most men who enlisted were in their late teens or early 20s. I personally went through basic training when I was 17 and it was a challenge, even at that young age. I cannot imagine trying to do it at 33!

A Sacrifice Like No Other

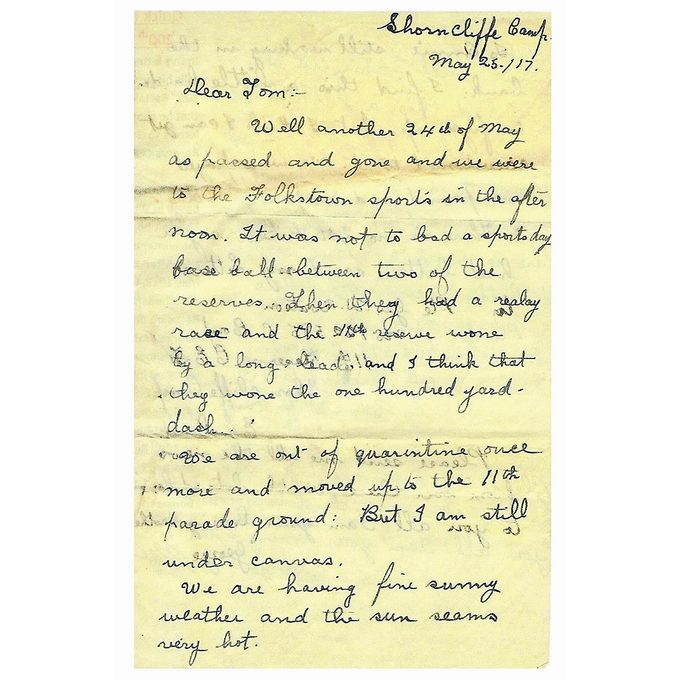

The 200th Battalion shipped out to Britain and, shortly thereafter, became part of the 11th Reserve Battalion on May 14, 1917. In January 1917, the personnel of the numerous Canadian battalions in England were placed into 26 new reserve battalions, and reinforced other infantry battalions in France and Belgium. Private George Watson wrote to his brother, Thomas, on May 28, 1917, telling him how he was at Shorncliffe Camp in southeast England and was still living in a tent. He also described the sports day that was organized at the camp to celebrate Victoria Day and how he got paid the princely sum of one pound, sixpence. Sometime before November 6, 1917, Private George Watson ended his time with the 11th Reserve Battalion in England and was transferred, as a replacement, to the 27th Battalion, an infantry battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. It originally disembarked in France on September 18, 1915, where it fought as part of the 6th Infantry Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division, in France and Flanders until the end of the war. The battalion was disbanded on September 15, 1920.

Returning to The Canadian Virtual War Memorial, I discovered Private George William Watson’s military service number, and that he had been declared missing on November 6, 1917. I was lucky enough to find the war diary for the 27th Battalion, for the month of November 1917. It documented daily reports filed by an army unit in the field and contains orders, intelligence reports, unit strength, and casualty reports of friendly and enemy personnel. In this war diary, I found that the 27th Battalion took part in an assault on the town of Passchendaele in Flanders, Belgium, as part of the 3rd Battle of Ypres. Passchendaele was captured by Canadian army units on November 6, 1917, the same day that Private George William Watson and nine other soldiers from the 27th Battalion went missing. In addition, the 27th Battalion lost 45 other men, killed in action, and 187 more were wounded.

The brutality of war denied George a known and honoured resting place, but his name appears at the top of Page 346 in the World War One Book of Remembrance in the Memorial Chamber of the Parliament of Canada. To honour George’s sacrifice, this page is displayed by a grateful nation every July 27th for public viewing. In addition, George’s name appears in The Menin Gate Memorial, in the town of Ieper (formerly Ypres), West Flanders, Belgium, which is dedicated to the 55,000 men who were lost without a trace. If ever you’d like more information on George and his story, visit this YouTube link.

George, I hope, wherever you are, that you are resting in peace. Thank you for going to a terrible war and helping to secure the freedom I enjoy today!

Check out more Remembrance Day stories honouring Canadian veterans.