At 63, Bestselling Mystery Author Louise Penny is Still Taking Chances

In her 40s, Louise Penny quit her job to author a series of hit crime novels. Now she's publishing a highly-anticipated political thriller—co-written with Hillary Clinton.

In the novels of Louise Penny, the twinkling village of Three Pines is a place to start over. The fictional location, modelled on Penny’s Eastern Townships hometown of Knowlton, Quebec, is a Canadian pastoral, its air redolent of crisp snowfall and woodsmoke, its streets populated by gregarious eccentrics, its doors never locked. It’s the place where Myrna Landers, a psychologist from Montreal, relocates to open a quaint bookshop, where Gabri and Olivier, a lovably quarrelsome couple, establish their dream B & B, and where the genius Sûreté du Québec detective Armand Gamache moves with his wife.

Three Pines is also quite possibly the murder capital of French Canada, with enough slayings to populate 17 whodunnit novels published between 2005 and 2021. There was the artist shot with a hunting arrow, the woman crushed to death by a marble statue, the seance attendee who apparently dies of fright. But these aren’t slasher tales, their pages smeared with gore and gristle. They occupy a lovely limbo between cozy drawing-room mysteries and psychological thrillers, where the macabre impulses of humanity are snuffed out by the warmth and kindness of the small town.

“What inspired the books is the idea that we can never guarantee our physical safety, but we can go a long way toward guaranteeing our emotional and spiritual state by having a community around us,” Penny says. “Bad things happen in Three Pines. People die, sometimes violently, but the community survives because of that sense of belonging and friendship.”

It’s an outrageously popular recipe, one that’s made Penny this century’s answer to Agatha Christie. “I realized that I wanted a safe place,” Penny explains. “Not necessarily safe physically, but a place for my heart and my spirit. And so I created Three Pines as that safe place. I thought if I feel like that, others will, too.”

She was right: her books regularly debut at the top of bestseller lists, have collectively sold 10.8 million copies and are published in 29 languages. Among her most ardent fans is Hillary Clinton, who’s said that Penny’s books helped her get through the humiliation and horror of losing the 2016 presidential election.

At 63, Penny has a chin-length pewter bob, a pair of sturdy thick-framed glasses and a wardrobe of elegantly drapey sweaters and scarves. She’s energetic, earnest and unvarnished, friendlier in a Zoom call than most people are in real life.

Like the quirky townsfolk of Three Pines, Penny has had to start over time and time again. She first refreshed her life when she quit her job at the CBC in her 40s to devote herself to crime writing. She did it again when she became a full-time caregiver for her husband, Michael, when he was diagnosed with dementia in 2013, at the age of 79. Then she had to adjust to a world without him after he died five years ago. And now she’s teaming up with Clinton herself to write a political thriller set in Washington’s State Department. It will be the first time in her literary life that she’s left Three Pines.

At the centre of Penny’s Three Pines novels is Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, the latest in a long line of mustachioed detectives that includes Hercule Poirot and Magnum P.I. Although Penny is an Anglophone, she chose to make the character a French speaker as a love letter to the culture and language that surrounds her in Knowlton. He’s a brilliant criminal diagnostician with refined tastes—a gritty street cop who loves opera, poetry and good red wine.

Gamache’s DNA can be traced directly back to Michael Whitehead, Penny’s late husband. “I thought, you know what? I’ll make this character the sort of person I want to hang around with. So I gave him all of Michael’s qualities that I admired—the integrity, the self-deprecating humour, the fact that he loves his family and knows how to accept love in return.”

Penny was 36 when she met Whitehead, then 60, on a blind date in 1994; she was working as a radio broadcaster with the CBC in Montreal, and he was the head of hematology at the Montreal Children’s Hospital. Early in their courtship, he took her to a Christmas party in the ward, where he dressed up as Santa Claus and she played his elf. She was struck by his compassion as he talked to the parents and cavorted with the kids.

At one point, she saw him standing with his nose up against the wall. When she went to investigate, she saw that he was crying. “He said it was because he knew which children would see the next Christmas and which ones wouldn’t,” Penny says. “If I hadn’t loved him already, I loved him from that moment on. I wanted to protect him.”

They married in 1996, two years after they met. They didn’t want to settle down anywhere either of them had lived before. Penny and Whitehead never had kids together, though he had three sons from a previous relationship. She says she lived a vagabond existence in the years before she met Whitehead, hopping between Winnipeg, Toronto, Montreal and Northern Ontario in her work for the CBC, and she yearned for a place where she felt like she belonged. She found it in the Eastern Townships—or more specifically in Knowlton, a village of 5,600 that’s close to nature and oriented around a cutesy main drag.

For their first Christmas at their new home, Penny and Whitehead attended an evening church service. The couple in the pew in front of them turned around and introduced themselves, inviting Penny and Whitehead to a potluck at their house. “The fire was on, the food was cooking, and all their friends became our friends,” she says. These townspeople—and their lavish dinners of coq au vin, tourtière and ripe Quebec cheeses—blueprinted the soul-satisfying meals and gatherings that show up in her books.

Marriage, and Whitehead’s financial support, also afforded Penny the opportunity to quit her job in 1996 and focus on writing full-time. Penny liked her work at the CBC, but she’d always harboured dreams of writing a novel. She spent years drafting a historical epic set in pre-Confederation Quebec, but never completed it. As a kid, she’d always been a fan of the golden-age mysteries by Agatha Christie and Dorothy L. Sayers. One day in the early aughts, she looked at her bedside table and saw a stack of crime novels. “I had one of those a-ha moments where I thought, My God, I should just write a book I would read,” she says.

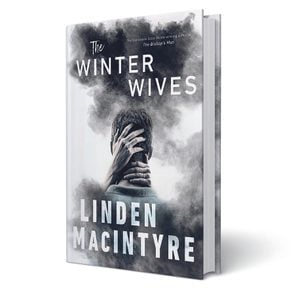

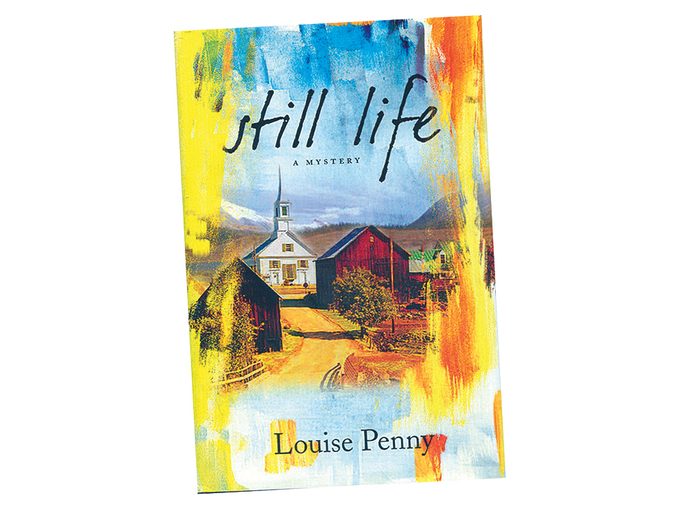

It took her nearly three years to write her first novel, Still Life, which introduces readers to Gamache and Three Pines. Between 40 and 50 Canadian and American agents and publishers turned down the manuscript, with some asking her to set the story in Vermont or England.

Finally, Penny entered her book in a crime-writing contest in the U.K., and it came in second. Within a few days, she had an agent. And within a few weeks, that agent had sold a three-book deal to Minotaur Books. “I thought, Are you kidding me? I don’t know how this book happened. How am I supposed to write a second? And a third?” she says.

And yet Penny managed to write the second and third books, and then a fourth and fifth. Soon her novels were winning prestigious Agatha mystery awards, named after Christie, and earning rave reviews in The New York Times and Publishers Weekly.

Her books were making enough money that she no longer had to rely on Whitehead for support, and the two of them inhabited a world as idyllic as the one she wrote about in her novels, with the added bonus of no murders.

Then, about a decade ago, Whitehead started forgetting things. He’d been a scientist his whole life, and suddenly he couldn’t do basic arithmetic. He was vague where he used to be specific. His doctors performed a suite of cognitive tests and determined he was fine, but Penny wasn’t so sure. The day of reckoning arrived on Penny’s birthday in 2013. Whitehead bought her a useless trinket—“a piece of crap,” she says—that she knows he would have never picked out if he was his usual self.

He told her he’d considered another gift, but it cost £20, which was far too expensive. “I asked him, ‘What would £20 buy?’ And he said it would buy a house,” she says. “That’s the moment I knew we couldn’t hide anymore.” Still, she says, she felt an immense calm, finally ascertaining what she’d long suspected to be true.

Whitehead was officially diagnosed with dementia that year, and Penny became his full-time caregiver. At first, he was high-functioning. She’d give him math quizzes to prolong his mental agility. For a while he could do them—until he couldn’t. She tried to never let him see her get angry. Sometimes her patience often dried up, often as much out of fear and sorrow as frustration.

One day, when the couple was driving on the highway, Whitehead undid his seatbelt. Penny told him to stop, but he kept unclicking the button. She was terrified of what would happen next—maybe he’d open the passenger door and tumble into traffic.

“At this stage, it was like my hair was on fire. But at that moment, I suddenly realized he’s not doing it on purpose. Michael would never do this. This isn’t Michael. This is the disease,” she recalls. “He’s not the one with the choice. I’m the one with the choice. And the choice I have is to go crazy or to adjust.”

Penny took Whitehead’s hand, a gesture that both calmed him and kept him from his seatbelt. After that, she stopped trying to control him. He’d take tissues out of the box and fold them, one by one, for hours. He’d rearrange the furniture from their bedroom while Penny was sleeping, and she’d move it all back again the next day.

“So what? Who cares? It gave him a sense of something to do. For some reason it was urgent for him. It doesn’t matter, as long as he’s safe,” she says. “That was what my life became.”

Unlike many dementia patients, who become aggressive as they deteriorate, Whitehead only grew gentler. Within a couple of years, as his motor skills devolved and his safety became more precarious, Penny installed a hospital bed and pulley system in their bedroom. And when the time came that she needed to bring in outside assistance, she didn’t hire professional nurses. Instead, two Knowlton locals, a couple named Kim and Danielle, volunteered to help her with feeding, bathing and other personal care. It was the peak of neighbourly altruism, something so heartwarming you wouldn’t expect to see it outside the novels of, well, Louise Penny.

Speaking of which: somehow, in the three years Penny took care of her husband, she also managed to publish three Gamache novels, including two New York Times bestsellers. She’d get up early every day and write for three or four hours before Whitehead woke. “I was able to go into a world that I could control, where goodness exists, where there was kindness and decency and courage in front of me,” she recalls.

For Penny, the joy of her setting and characters always defeats the murder and monstrosity that fuel her plots. Her books are formulaic in the way of fairy tales or parables, where good always triumphs, but not before revealing some horrific truth about the human experiment.

In September 2016, three years after his initial diagnosis, Michael Whitehead died at home at the age of 82. In a sentiment that will resonate with many caregivers, Penny was struck with an overwhelming sense of relief—that his suffering was over, and that hers was, too. “That lasted a few weeks, to be honest,” she says. “After all the support he’d given me, I felt I’d finally been able to support him.”

She was concerned that she wouldn’t be able to go back to Armand Gamache, Whitehead’s literary avatar, but she found the writing process to be a source of solace. She felt like he was around her again, the way Michael used to be.

As she kept publishing books, her fan base kept growing. One day in 2016, Penny’s American publicist read an interview with Betsy Ebeling, a human-rights advocate and Hillary Clinton’s childhood best friend; the two met in Grade 6 at Eugene Field School in Chicago. Ebeling mentioned in the article that she was a Penny megafan, and the publicist arranged a meeting. Soon, Ebeling and Penny had become friends, and Ebeling brokered an introduction to Clinton, who was also an acolyte. In 2017, Penny visited Clinton at her home in Chappaqua, New York. Clinton later brought her husband, Bill, and daughter, Chelsea, to Quebec to celebrate Penny’s birthday. (Ebeling died of breast cancer in 2019.)

“I find [most crime thrillers] like an anvil hitting me in the head, as one more horrible dismemberment of some young woman happens,” Hillary has said. With Penny’s books, she found a gentle temperament, a series of exquisite puzzles and a fresh setting—she’s said that until reading the Three Pines novels, she had no idea that Quebec had been settled by British Loyalists. “I read, I learn and I escape, and I can go deeper and feel a connection to your characters,” she told Penny in a recent episode of her podcast, You and Me Both.

Over the past year, Penny and Clinton have been collaborating on a political thriller, State of Terror, which follows a newbie female secretary of state forced to contend with a phalanx of terrorist attacks. (Bill Clinton has a similar co-authorship gig with James Patterson on a series of books about a 007-esque U.S. president.)

Penny has said that in the planning period for the book, she asked what Clinton’s worst nightmare would have been during her stint as secretary, and this story was it. Political thrillers have sharper edges than Penny’s usual brand of cuddly crime fiction, but she found the transition exhilarating. “Maybe it was a bit of a palate cleanser, or there was enough similar that it didn’t feel completely different. But it was different enough that it was exciting,” she says.

The book comes out in October, only two months after Penny’s latest Gamache novel, a post-COVID tale aptly titled The Madness of Crowds, about the threats that emerge when a controversial academic draws a cultish following. This might be the first time Penny has to duke it out against herself on the New York Times bestseller list.

Next, check out 10 Indigenous authors you should be reading.