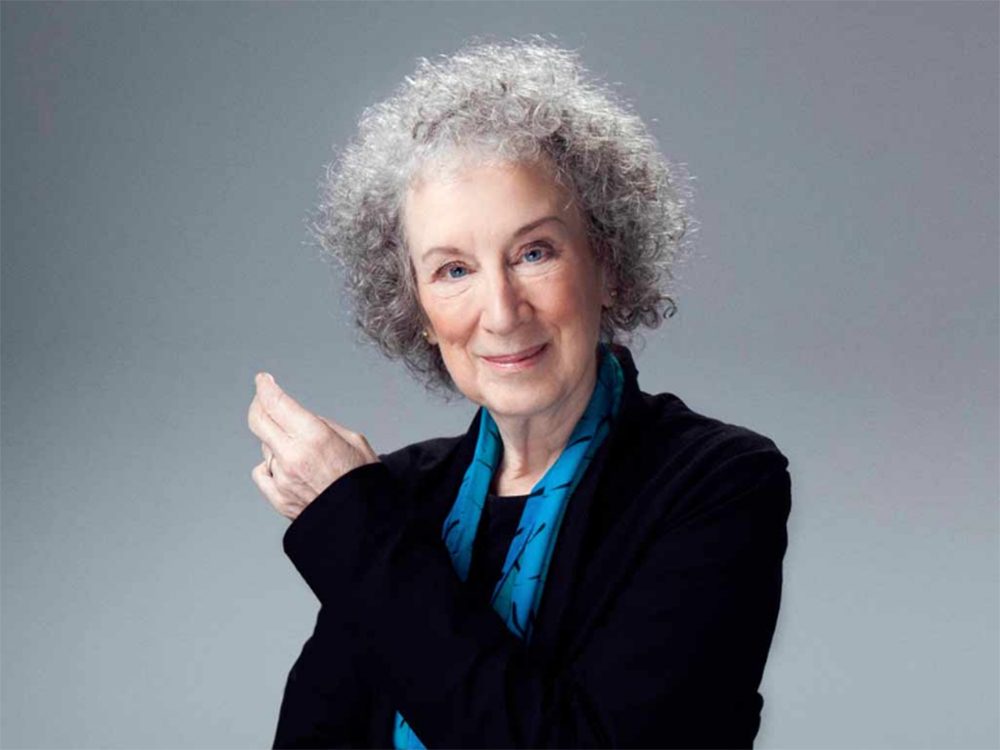

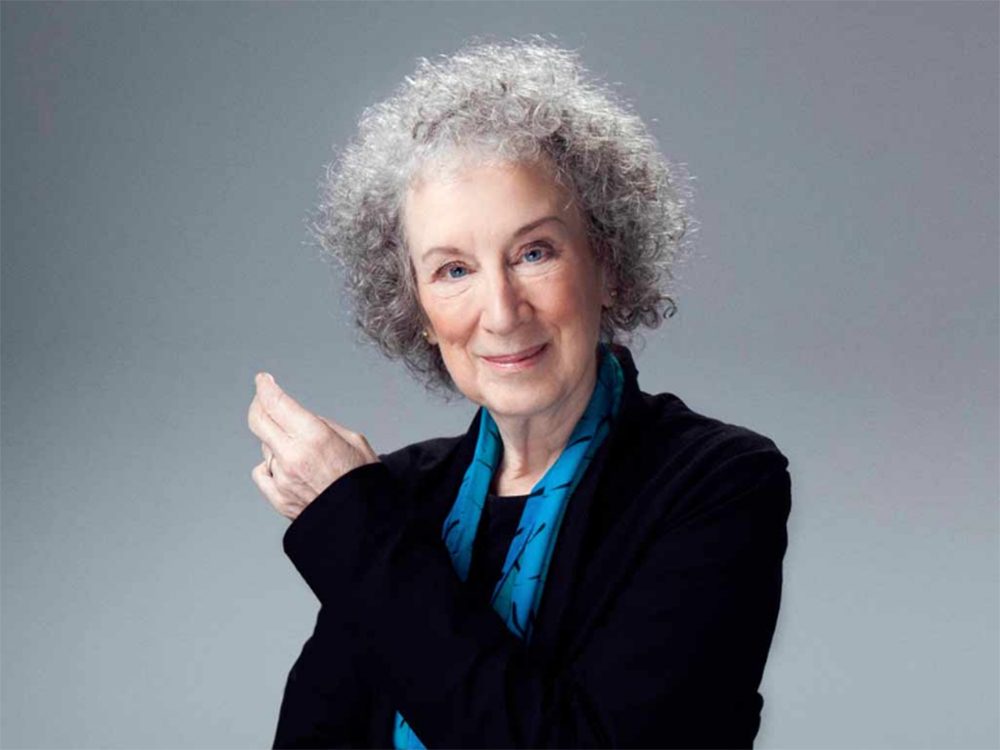

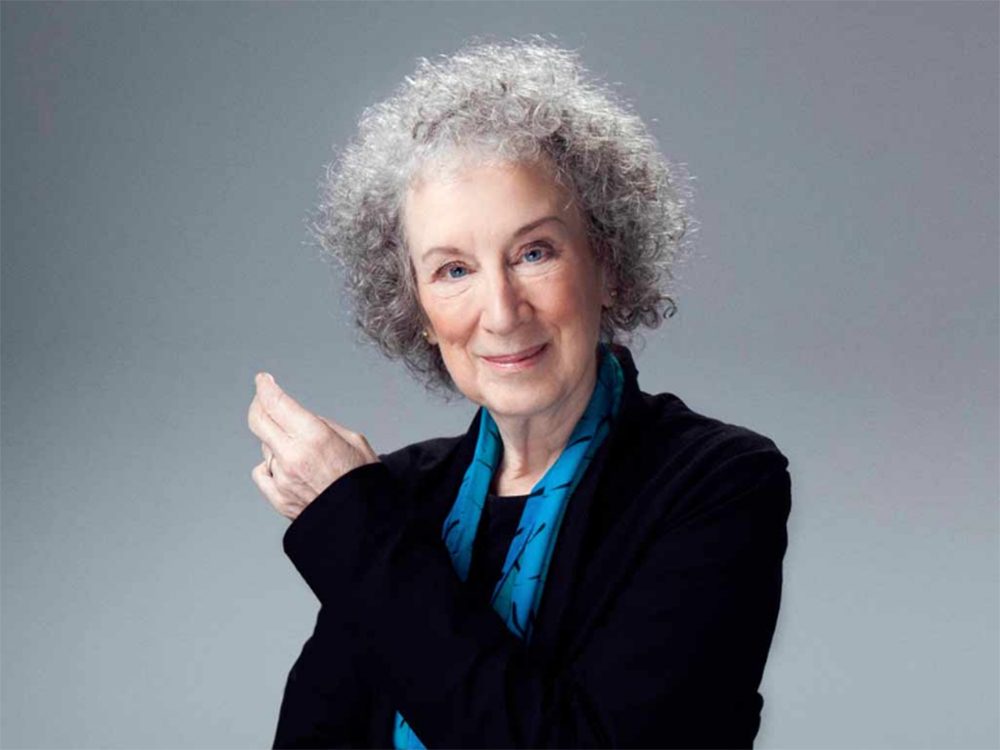

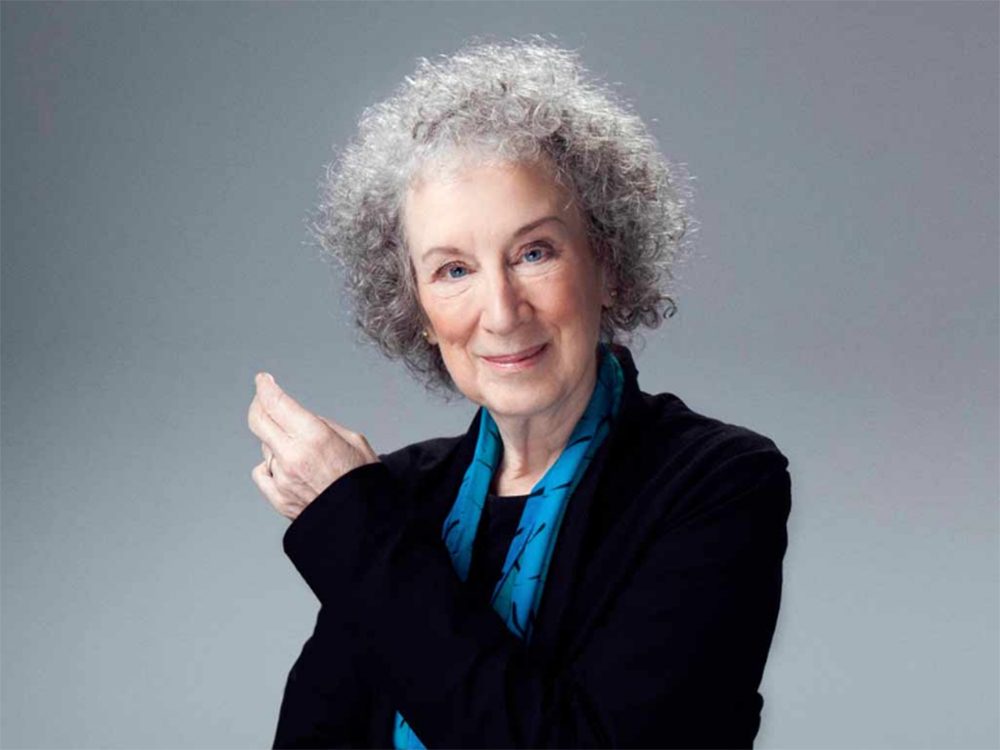

15 Minutes with Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood has a knack for imagining what’s to come. Over the course of more than 60 books and a career that stretches 50-plus years, the Booker Prize-winning author has eerily anticipated everything from the 2008 recession to lab-grown meat. In her new novel, The Heart Goes Last, Atwood conjures yet another sobering vision. Set during a devastating economic collapse, the book is about citizens of a closed community who voluntarily split their lives between freedom (as residents of a well-appointed town) and captivity (in the town’s mysteriously money-making prison). But Atwood isn’t a fatalist. She believes if we take charge of even the most terrifying scenarios now, we can set the world on course. Here, she offers insights into the present and some pointers on how to deal with what might come next.

Reader’s Digest: You write a great deal about dystopian futures. In 1985’s The Handmaid’s Tale, you conceived a society that treated women as reproductive machines. More recently, there was the post-apocalyptic world of the MaddAddam Trilogy, and now this one. Are you stressed about what’s around the corner?

Margaret Atwood: It’s probably not going to be my problem, but it will be yours. Mind you, if those dystopian visions kick in within the next 20 years, I might well be around. With a lot of these things, it’s not a question of whether but when-unless we change our way of viewing the world.

Are you hopeful that we can do that?

I see a lot of positive signs. Even Mr. Harper has said in 100 years we’ll be decarbonated. Well, sorry, but 100 years is not soon enough. Still, the mere fact he’s saying it is a big change from 2005.

Do you hope political leaders will read this book?

People like that say, “Oh, Margaret, you’re so far-fetched!” They don’t like having what they’re actually thinking of doing out there, in black and white.

Reader’s Digest: Your descriptions of life outside the walls of the closed community are terrifying-roving gangs poised to commit all manner of violence. I think I’d join the community. You make a previously unthinkable scheme-volunteering to be a part-time prisoner-seem downright appealing. Would you sign up?

Margaret Atwood: Undoubtedly. Unfortunately, there isn’t any out. Once you’re in, you’re in.

Residents are trapped in this deal for life, and then things start to go horribly wrong.

And things start to go askew. Because this is prison as a for-profit enterprise, and once you have prison as a for-profit enterprise, you have to figure out where that profit is going to come from. Right now [in the United States], there are for-profit prisons that make their money by warehousing prisoners from other states. As they say themselves, in order for a prison to be profitable, it has to be full. So the end goal is obviously to make more criminals.

After writing this book, have you gained any new insights on the way Canada is navigating freedom and security-in our anti-terrorism laws, for example?

Let’s make a list of all of the kinds of things that might kill you and what people are doing about them. No. 1: car crashes. How hard would it be to reduce the speed limit? It would be a little bit harder to put [sensors] into cars to keep people from driving drunk, but those exist. That would save a lot of lives and bring down the cost of hospital bills and what you’re paying as a taxpayer.

Whereas the likelihood of a terrorist attack, you’re saying…

You’re actually at more risk of being hit by lightning. Helpful hint: don’t go out on the golf course in a thunderstorm waving a metallic club in the air. Don’t have a shower in a lightning storm. The electricity goes through the water.

What a strangely optimistic thought: we can stop worrying about terrorism and focus on meteorology. Speaking of looking at the bright side, you skewer extreme positivity-the idea that you make reality with your thoughts-in this book.

There’s something to it, but there’s not everything to it. There are some things that you cannot change with your thoughts. Like the idea it’s your own fault you’ve got cancer, that kind of thing, which is so punitive.

Is there something disturbing about the idea that we’re so often encouraged to smile and continue smiling as things fall apart? In the world as well as in our personal lives?

Well, you most likely will feel a bit better if you smile. It does have a chemical effect.

Most of the horrific acts in this novel are conducted while the villain is smiling.

It’s so often true.

So should we be suspicious of smiling people?

Not as such. I think it’s all very well to have a positive attitude; you probably wouldn’t get out of bed in the morning if you didn’t have one. But it doesn’t mean everything’s okay all the time. Smiling is actually a very odd thing biologically, because most animals show their teeth as a threat mechanism, whereas we show our teeth as a happy, friendly gesture. Why is that?

I guess our teeth aren’t quite as pointy as those of most animals.

Might be that. I’m showing you my non-pointy teeth, like a handshake is to show you that I don’t have a sword in my hand. I would be interested to ask an evolutionary biologist about the smiling. I know that in Renaissance portraiture, aristocrats didn’t smile, to show that they were superior and didn’t have to please anybody, whereas peasants did smile to show that they were subservient.

Reader’s Digest: Now that we’re talking about human relations, the future of sex, as presented in The Heart Goes Last, seems pretty racy. You illustrate why sex with robots, even really good robots, might not be satisfying. One of your characters is even hospitalized after a robotic romp gone wrong.

Margaret Atwood: That’s just because it’s early-stage technology. Remember your car phone, how big it used to be? All of these are tweaks.

Are you optimistic about the role robots will play?

Am I optimistic? How is that even a question? I think some people who don’t like interacting with humans very much will be happier. Others, who want total control over their relationships, will be able to program that. And [scientists] are actually, in fact, really working on those things.

From the online writing community Wattpad to LongPen, a device that allows authors to sign books remotely, you’ve always been an early adopter-even an inventor-of new technology. What makes you so willing to experiment?

Growing up in the woods.

We have the northern woods of Ontario and Quebec to thank for your inventiveness? Why?

Limited range of tools. No store where you could go and buy things. No person you could call to come and fix them. So you learn to fix things with whatever happens to be at hand. That’s why I put duct tape in the future in Oryx and Crake. It’s so useful. I’m a big fan of Gorilla Glue, too. And No More Nails.

Your appreciation of handy tools extends to social media, like Twitter, which isn’t the only short form you favour, apparently. You also make a point of reading the messages on bathroom walls.

I always read them.

Why?

It’s just interesting that people would write things. They wrote [messages like that] in Roman times, as well.

What do you glean from that?

People used to carve things like “John loves Mary” on the pyramids. It’s part of the same phenomenon-“I was here.” And the washroom walls, some of them are quite witty. Little poems.

Have you ever added to a wall?

No. But I’ve quoted some of them. “I love so-and-so, yes I do./He’s for me and not for you.”

How do you find creative inspiration-other than reading bathroom stalls? You’re so prolific.

Deadlines. I like deadlines. I think it comes from high school and having to get your stuff ready for final exams.

Reader’s Digest: You’re taking care of your artist’s mind. What about your artist’s body? I’m sure you’re aware of all the studies that suggest sitting is the new smoking.

Margaret Atwood: And yet I spend so much of my life doing it.

It is a job hazard for writers.

I’m gonna die!

So do you have a physical regimen?

Yes, I do a lot of walking. I have a step counter.

You recently tweeted that, without your vitamins, you’d shrivel into dust.

Exactly. There are two books in which that happens. One is H. Rider Haggard’s She, and the other one is James Hilton’s Lost Horizon, in which you only get to be young and beautiful if you stay in Shangri-La. And there’s the film Night at the Museum. If you go outside the museum and dawn rises-poof, dust.

You recently contributed the first manuscript to the Future Library, a public art project in which one writer a year will provide a manuscript that won’t be read for a century-at which point it will be published in hard-copy form. A grove has been planted in Norway that will provide the paper that the books will be printed on. What was it like to write for readers in 2114?

Very interesting. A lot of things had to be taken into consideration. Will the language have changed? Will the technology have changed? No doubt, but we don’t know into what. The things that you have to research when you’re writing a 19th-century novel are the things that everyone back then took for granted because they were so ordinary that people just didn’t write them down. [When you’re writing for future readers,] you’re thinking about that all the time: what will still be there, what will not be there. You just don’t know.

So how did you work that out?

I can’t tell you.

I know you’re not allowed to reveal what you wrote, but-

Well, everybody went “Sniffle sniffle” during the handover thing in the forest.

People cried during the ceremony in Oslo, Norway, where you presented the library with your manuscript? Because they weren’t going to be able to read it?

No, because what they were thinking about, really, was death. Let us just say that anything that’s written down implies a reader. There will be people. They will be able to read. There will be a forest in Norway. There will be paper made. So the project is a great big hope for the future.