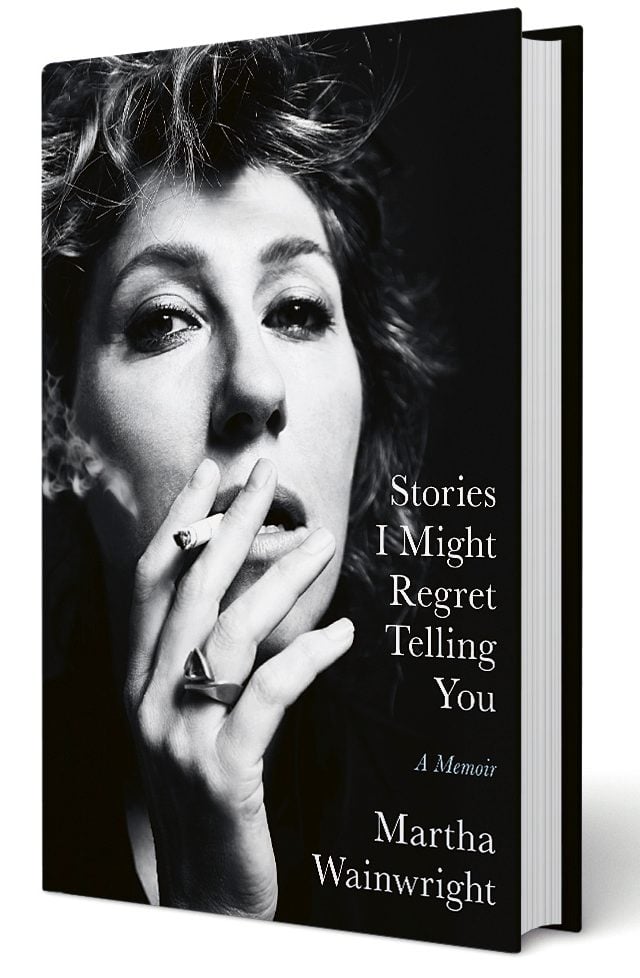

Martha Wainwright’s Fiery Memoir is a Must-Read

The gifted songwriter's new book is a heartfelt and freewheeling tell-all about Canada's most famous folk family.

Martha Wainwright has mother issues. And father issues. And brother issues. Her push-pull, hot-cold, love-hate relationships with her family members provide the fuel for her new memoir, Stories I Might Regret Telling You, a freewheeling tell-all the likes of which we rarely see in the age of publicist-muzzled celebrities. Wainwright, a gifted songwriter with a voice that sounds like Kate Bush after a late night in a smoky club, has released nine albums. She’s also famously the daughter of folk singers Loudon Wainwright and the late Kate McGarrigle and the sister of the baroque troubadour Rufus Wainwright. Her memoir lays bare both her aching adoration for her family and her many, many grievances. In Wainwright’s telling, the wholesome Canadian icon McGarrigle insults her daughter in one breath and consoles her in the next. Her rakish father admits he pressured Martha’s mother to get an abortion instead of have her. Rufus is her closest ally as well as her rival, both for their parents’ love and the public’s attention.

Wainwright comes across as a bohemian raconteur who darts around in time and makes digressions within digressions. She traipses from her mother’s sprawling Victorian house in the Anglo suburb of Westmount in Montreal to her father’s London flat in Hampstead Heath. She recounts her years taking drugs and playing gigs in the Chelsea Hotel and the East Village in the ’90s and early 2000s. She catalogues her love affairs and hook-ups and the challenges of balancing music and motherhood (she has two children). But it always comes back to her family of origin. Back to her competitiveness with Rufus and her envy of his closeness with Kate. Back to the time her mother told Martha she was mediocre and unintelligent, and Martha responded by shoving Kate to the ground. Back to when she learned that her father’s song “I’d Rather Be Lonely” was about her and the time they’d lived together. “I kept my dad from doing what he really wanted to be doing, which was music and being by himself,” she says.

Where most families might bury their feelings or seek out group therapy, the McGarrigle-Wainwright clan have spent decades airing their feuds in their searing songs—and now, in this equally acidic memoir. Martha’s first hit song, whose title is too vulgar to be printed in these pages, was inspired by her futile attempts to win Loudon’s love (she now says it could be about a number of men she’s known). “I will not pretend, I will not put on a smile, I will not say I’m all right for you,” she sings.

Taken together, these works are as much about the family’s dirty laundry as they are about their intense bond. And by the end of the book, Martha seems to have come to terms with her place in this Greek tragedy. “[We are] a broken family whose members hang on tight to each other nonetheless,” she writes. “We fight, but we make up relatively quickly. We try not to hold grudges, but it’s hard not to.”

By processing their pain so publicly, the McGarrigle-Wainwrights have done something remarkable: they’ve turned their squabbles and resentments into a vast musical mythology, a web of lore haunted by jealousy, casual cruelty and things previously unsaid. Their songs, and Martha Wainwright’s deep gash of a memoir, speak to each other and to their audience, each new entry made more poignant by its connection to the previous ones. It’s a powerful collective reckoning—and a canny publicity ploy. Because more than most famous Canadian music families, we know these people. We care. We’re invested. “Journalists often ask if music is something I was ‘made’ to do,” Martha writes. “The answer is yes, I was made to do it by my parents, but I liked it and I wanted the attention.” Decades after it all first began, we’re still listening.

Next, take a look back at the most scandalous royal memoirs ever published.