An Inside Glimpse of NFL Player Mike Webster’s Tragic Final Days

In a story that first appeared in Reader’s Digest in 2003, the former Pittsburgh Steeler centre shrugged off repeated brain injuries and paid the price.

In Will Smith’s 2015 movie Concussion, the actor portrays the pathologist Bennet Omalu, who first revealed proof of football’s deleterious effects on players’ brains and published breakthrough papers in medical journals on the degenerative brain disease he discovered, chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. Pittsburgh Steeler centre Mike Webster was the first NFL player Omalu autopsied.

In its March 2003 issue, Reader’s Digest wrote about Webster’s shattered life. Our piece addressed the role that the thousands of concussions Webster sustained during his football career affected his brain and contributed to his death in 2002 at age 50. The article is published in its entirety below.

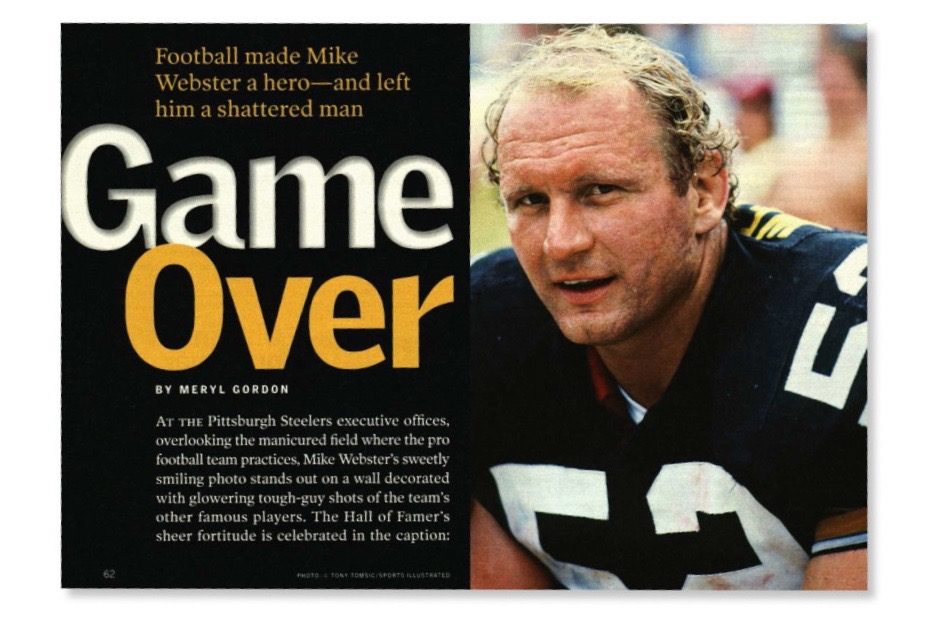

At the Pittsburgh Steelers executive offices, overlooking the manicured field where the pro football team practices, Mike Webster’s sweetly smiling photo stands out on a wall decorated with glowering tough-guy shots of the team’s other famous players. The Hall of Famer’s sheer fortitude is celebrated in the caption: Webster “played the most seasons (15) and games (220) in Steeler history.”

But in Webster’s rented town house in the Pittsburgh suburb of Moon Township, his family has kept a much sadder tribute—a sheaf of Webster’s scribbled notes torn from a legal pad, page after page of heartbreaking gibberish, the legacy of a brain injury sustained while playing centre for the Steelers. His anguish is evident as he writes about his mental state: “…deep, confusing, twisting fishing line tangled up mess of confusing things go on all the time.”

Mike Webster died of a heart attack at age 50 on Sep. 24, 2002, at a Pittsburgh hospital. This undersized six-foot-two athlete, who through force of will turned himself into “Iron Mike,” led a life of extraordinary career highs—followed by a slowly devastating decline.

The years of being butted repeatedly on the head took a brutal toll. An avid reader, Webster could still devour books on Winston Churchill and World War II, yet his memory was so fragmented he couldn’t remember the simplest things, sometimes sleeping in his car by the side of the road because he didn’t know how to get home.

In October 1999, Webster was awarded an NFL disability for traumatic brain injury. His story, however, isn’t just a cautionary tale about gridiron injuries. It’s a saga about a man who was loved deeply by family and friends, but who lost the relationships he prized most. A man who, despite his anger at his own fate, was nonetheless trying at the end of his life to teach his beloved sport to a football-crazy son. A man whose disturbing end has left his former teammates with questions that will forever haunt them.

Mike Webster grew up on a potato farm near Tomahawk, Wisconsin, where rooting for the Green Bay Packers was a religion. Even as a young boy, he saw that sports was a small-town way to shine. The second of six children, he didn’t have an easy childhood: His parents divorced when he was ten, and a year later his home burned down, with Mike, his mother and siblings barely escaping the inferno. In high school, Webster moved in with his dad, and went out for wrestling, then football. “He couldn’t sleep the night before a game, he was so wound up,” says Bill Webster, Mike’s father. “I don’t think he cared about being a hero, he just liked the game.”

While at the University of Wisconsin on a football scholarship, he met his future wife, Pamela, who worked in the athletic department ticket office. “He had such kindness in his heart,” she recalls. “He’d open doors for me, he’d call when he said he’d call. And he had such a soft spot for children.” The couple married shortly after the Steelers drafted him in the fifth round in 1974, and eventually had four children: Brooke, now 26, sons Colin and Garrett—24 and 19—and Hillary, 15.

Grateful to be playing in the big time, Webster overcompensated for his size by becoming the hardest-working, play-with-pain member of the team. “Mike would be the first one at the stadium and the last to leave, he was so afraid to fail,” recalls Pamela. “Even on vacations, he’d pack the football ‘sled’ and push it across a field.”

Webster’s former teammates remember him as a quiet, determined man who seemed blessed with a photographic memory—and who studied the game as if every play depended on him. “You look at the centre position as the foundation,” says legendary running back Franco Harris. “Mike was a guy you could always count on.”

He also relished his indestructible image. On one occasion, Webster showed up at a game on crutches, with torn cartilage in his knee, played anyway and had surgery afterward. His toughness made him a winner: He was voted onto the All-Pro team six straight years, won four Super Bowl rings, and joined the greatest players ever in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

But play after play, year after year, Webster slammed into much bigger players, their helmets crashing into his like battering rams, their forearms pounding his head. And the beating left its own legacy. “He got his bell rung all the time, just like the rest of us,” says former teammate Rocky Bleier.

Also like the others, he tried to shrug it off. “Everybody gets injured, but most injuries aren’t reported,” says Miki Yaras-Davis, director of benefits at the NFL Players Association. Players worry about ending their career, she says. “Some of the guys will treat a concussion like a hangnail.”

Webster was never officially treated for a concussion—“He never complained about anything like this,” says Ralph Berlin, the Steelers trainer during Webster’s playing years. But doctors say he suffered multiple concussions, among his many other injuries, on his way to gridiron glory.

Soon after his last season in 1990, Webster moved, at his wife’s urging, back to her hometown of Lodi, Wisconsin. That’s when, as Pamela says, “Mike changed.” He seemed physically disoriented and started to behave strangely. Webster had always handled their financial affairs, so his wife was startled to discover that he wasn’t opening mail, or paying bills, or even filing taxes. This reliable family man who used to read his children Bible stories at bedtime began to get in his car and disappear for days. “I didn’t realize he had a brain injury,” says Pamela. “I just thought he was angry at me all the time.”

Money quickly became a problem. Webster had several million dollars in assets when he retired, so it shocked Pamela when their Victorian house was foreclosed 18 months after he left football. Webster’s finances remain a muddle, but from conversations with his family and lawyers, it appears he poured most of his savings into investments that went bad.

The financial strain couldn’t fully explain his increasingly bizarre behaviour, however. Pamela put up with it for a while, but the couple separated for the first time around 1992 (she finally divorced a reluctant Webster last March after years of living apart).

Meanwhile, Mike began drifting back to Pittsburgh, spending more and more time there. Former colleagues soon began to hear disturbing stories about him, but no one knew what was wrong, and Webster was mystified and frustrated himself, embarrassed that he couldn’t seem to hold a job or even remember scheduled meetings.

The Steelers’ now-retired public-relations man Joe Gordon says, “I got a call from the manager of the Amtrak station, saying Mike is here and he slept here last night.” Gordon found Webster there, poring over brochures and talking excitedly about a plan to market celebrity photos—“This could be big”—but he had no place to sleep. At the team’s expense, Webster was put up for six weeks at the Pittsburgh Hilton, before decamping to a $25-a-night joint.

Too proud to ask his teammates for help, Webster was eventually befriended by a fan, Sunny Jani, who sought Mike out after reading about his troubles in the newspaper. “He was my hero,” says Jani, who owns a grocery store and sports-memorabilia shop. Jani began to handle the increasingly frequent crises, bailing Webster out of awkward jams. “Mike would call at 2 a.m. and say he’s lost.” Webster saw a slew of doctors during this period in the mid-’90s, including one who told him he appeared to be brain-damaged. “Have you ever been in a car accident?” the doctor asked.

“I’ve been in 350,000 car accidents,” Mike replied. Some half-dozen times Webster requested an application for disability payments from the NFL, but he never followed through.

By the time Webster entered the Hall of Fame in July 1997, he had become a recluse, in agony from herniated discs and hand injuries, impoverished and angry at his fate. He put on a brave front, though, for his two daughters. His youngest child, Hillary, who was living in Wisconsin with her mother, says that in recent years, “My father called me every night.” But his two sons, who lived with him at different times, saw a more tortured side. Colin remembers that his father was shaking so much from his condition that his desperate solution was to buy a police Taser gun. “He’d zap himself to calm his nerves. He’d do it 10 or 20 times to relax.”

Webster was prescribed Ritalin to control his mood swings, but in 1999, shortly after his regular doctor moved away, the athlete was arrested for forging Ritalin prescriptions. He gave an emotional news conference apologizing for “any embarrassment and sadness” he’d caused, and was sentenced to probation. That same year, his lawyer, Robert Fitzsimmons, finally won Webster a $115,000 yearly payment from the NFL for a football-related disability. (That payout ended with his death, but his two youngest children now receive $1,500 a month each.)

“He wanted to provide support for his family,” says Fitzsimmons, who pulled together a raft of supporting medical records, and brought in a psychologist from Marshall University Graduate College, Fred Jay Krieg, to examine Webster.

“Mike had dementia due to head trauma, a series of blows to the head over a period of time,” Krieg says. “He couldn’t concentrate, he had difficulty focusing, the conversation was rambling.” Krieg adds there was no other explanation for Webster’s deterioration; the repeated banging of his brain against his skull had damaged the brain’s nerve cells.

Since Webster was so passionate about football, it was painful for him to accept that the sport had left him permanently impaired. It was too late to undo the harm, however, just as it was too late to dissuade his son Garrett from playing. “When I was young, he said he wanted me to be somebody, like a lawyer,” says Garrett, who moved in with his father three years ago. But the towering six-foot-nine, 340-pound teenager figured he was built for the game, and made it clear to his father he was going ahead with or without help. So Webster launched a single-minded coaching clinic. He taught his son plays, watched game tapes with him, even tried to run with him despite knee and back injuries. Mike was also on the sidelines at every game. “He tried to stay low-key,” says Moon Area High School’s football coach Mark Capuano. “He preferred it if people didn’t recognize him.”

The last year of Webster’s life brought new woes: His divorce became final, his health worsened and his finances collapsed again. He had been receiving money from annuities and the disability payment—much of it went to alimony and child support—but the IRS then garnished almost all of his income for unpaid taxes. He and Garrett were ousted from their apartment for unpaid rent; Jani helped pay for a new place, but Webster couldn’t afford furniture. The father and son slept on the floor, surrounded by pizza boxes. Often unable to pay for medicine, Webster would shake so hard he couldn’t drive his son to school. “I couldn’t leave him in that situation,” Garrett recalls. “I had to be the dad sometimes.”

On a Friday night this past September, Webster went to his son’s football game. But as the weekend progressed he complained of feeling ghastly. “He woke up Sunday morning, his lips were purple, he was sheet white,” says Garrett. But Webster refused his panicked son’s entreaties to go to a hospital, in part because he didn’t have insurance. Finally, later that night he let Jani drive him there; doctors said he’d had a heart attack. Garrett was with his father when he went into a coma and then passed away on Tuesday: “I took it hard when they told me he was going to die. But when he died, I felt this calm come over me. I could feel a pat on my shoulder, almost a whisper in my ear, ‘Everything’s going to be all right.’”

On a chill afternoon in November, Steelers owner Dan Rooney sits in his office, fondly recalling Iron Mike. “He’d cut off his sleeves in the freezing cold, zero degrees, to intimidate the other teams,” Rooney says with a grin. Over the years he picked up expenses for the financially beleaguered Webster and even paid for almost all of his $7,600 funeral. But Rooney refuses to believe Webster’s problems were more than psychological or that he was truly entitled to an NFL disability. “Everybody gets hurt in football,” he says, “but very few players get hurt permanently. He wasn’t eligible, to be honest. But we did get it for him.”

Midway through our interview, Rooney jumps up and strides out into the hallway to give a warm “Welcome back, how are you?” to Steelers quarterback Tommy Maddox. Three days earlier Maddox had suffered such a serious concussion during a game that he was temporarily paralyzed. “I’m feeling good,” the quarterback says, moving stiffly. An hour later, standing on the sidelines watching practice, Maddox complains to me: “I’m really upset that they won’t let me play.”

This from a man who 72 hours earlier didn’t know if he’d ever walk again. But then, Maddox wasn’t there at Mike Webster’s funeral. Grieving teammates were, and they felt shaken by this glimpse of their own mortality. “All these guys were talking at the funeral about maybe they should get checkups,” says Franco Harris.

The weekend of the funeral, Harris went to see Garrett Webster play football and was impressed by the teenager’s potential. But Harris thinks about the risks that Mike’s son will face. “A lot of guys look back, and they love the game,” says Harris. “But there are some who can’t walk, who find it hard to do simple things. You can’t help but wonder, is it worth it?”