As a Teenager, I Gathered Paints for Maud Lewis

During the 1960s, my father kept up a frequent correspondence with Maud Lewis, one of Canada’s most famous folk artists.

In the summer of 1965, my father, the artist John H. Kinnear, read an article in the Star Weekly titled “The Little Old Lady Who Paints Pretty Pictures.” It told of a then unknown, self-taught painter in Marshalltown, N.S. named Maud Lewis, who was “small and somewhat crippled by arthritis,” and poor.

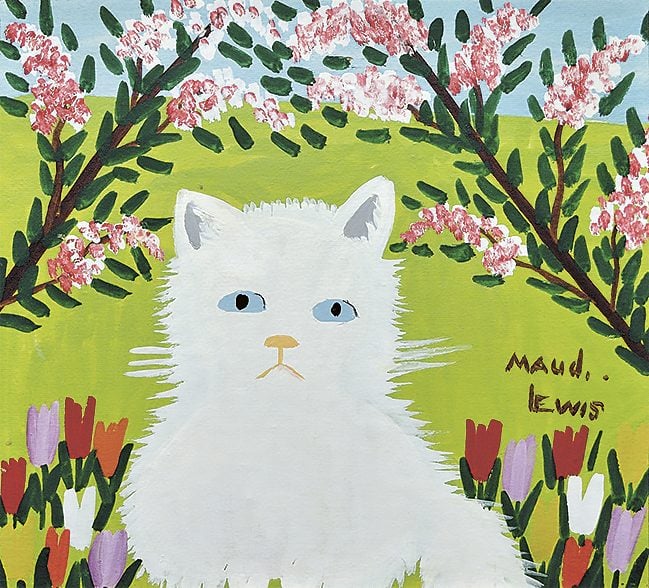

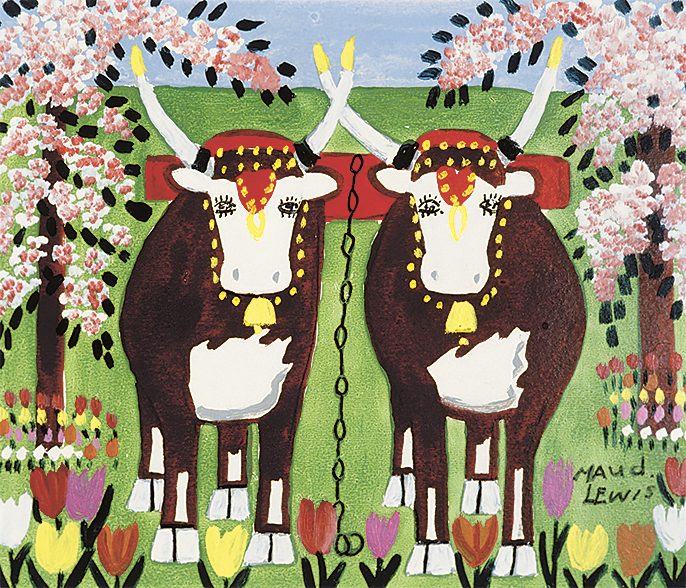

“Maud and her husband Everett, both in their mid-60s, live in a house so small that it might have been built for Tom Thumb,” wrote Murray Barnard in the article. “The couple have no electricity or running water and none of the other comforts of life.” The newspaper showed examples of Lewis’s colourful paintings of cats and horse-drawn carriages, and included photographs of her at work and standing in front of her tiny, painted home.

Maud Lewis’s debilitating condition and life of penury struck my father, and he decided to help her. He, too, knew pain and hardship—while fighting in the Second World War, he had been captured and made a prisoner of war on three separate occasions, twice by the Germans and once by the Italians, and successfully escaped each time. In autumn 1965, he mailed Lewis a box of paints, sable brushes and standard Masonite boards, which I had primed. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasted until Lewis passed away from pneumonia in 1970.

My father fell in love with the simplicity of Lewis’s art and found beauty in her unmixed rainbow palette of colours. Even more, he recognized that her paintings deserved archival-quality materials, and that, as an unschooled painter, she was working on found objects or wallboard, with house paint that would eventually peel from its base and disintegrate. He wanted her to have something that would stand the test of time.

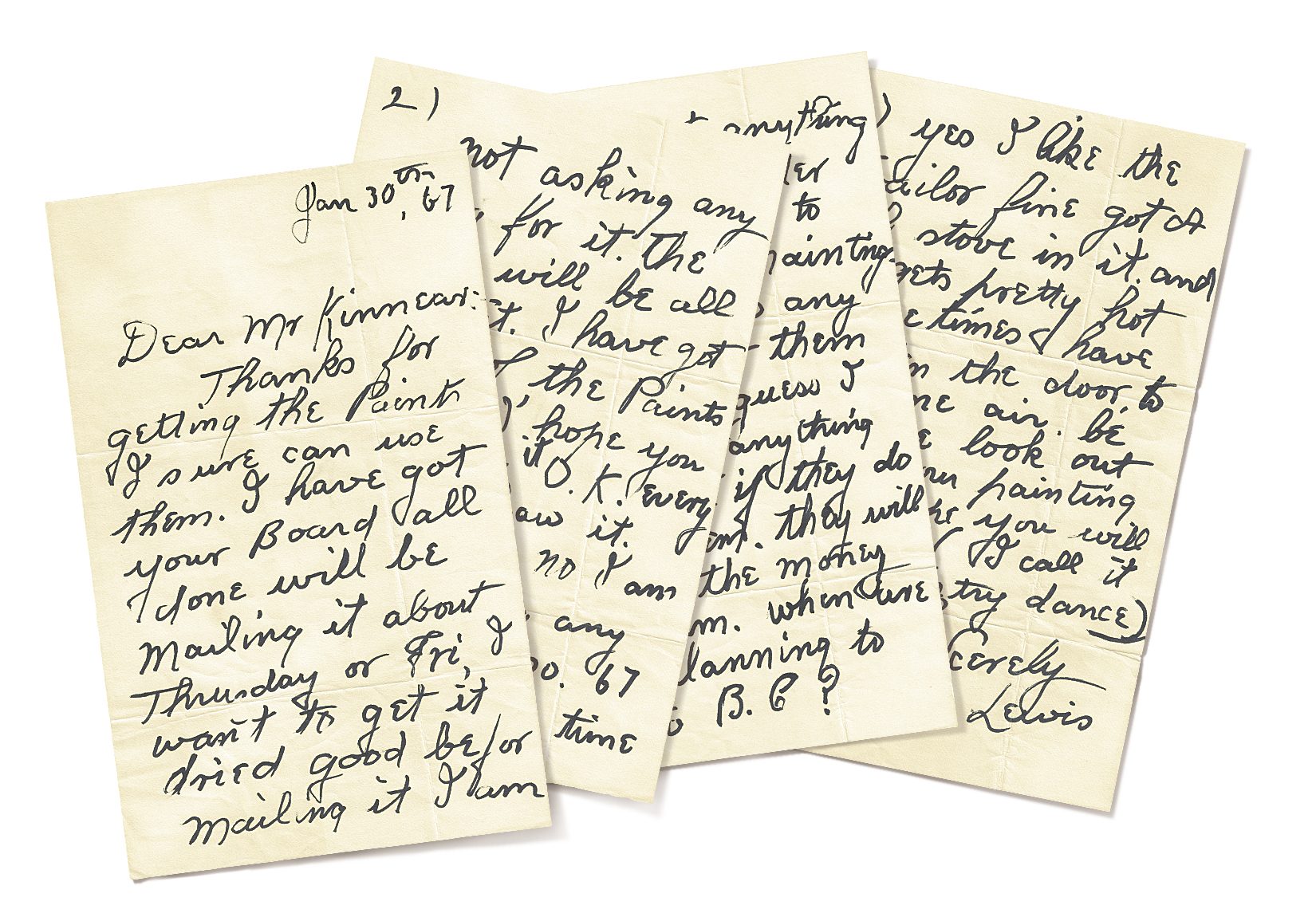

Lewis thanked my father for his original gift, and he followed this note of thanks with a second package of supplies—more archival paints plus gessoed boards. After this second package, Lewis insisted on reimbursing my father with her paintings. She asked my father to continue to send her the gessoed boards and paints that she couldn’t find in Nova Scotia.

When I was in my early teens in the 1960s, there were only a handful of art supply stores in London, Ont., where we lived. My father would give me a wink and ask, “Shall we give our legs a good sprint?” I knew that meant it was time to start the eight-block walk over to Anderson’s Art Store to replenish his stock and pick up extra paints for Lewis. My father kept a list of paint colours Lewis requested—she would ask for tubes of acrylic paint in bright red, daffodil yellow, black, sap green, white, brown and various shades of blue—and we would also take home some of the heavy jars of gesso that were needed for priming.

Getting supplies for Lewis was not out of the ordinary for me—as a young girl, I often worked in my father’s art studio. It was there, surrounded by art and artists, that I felt most comfortable and at home. Even now, I still love the smell of Dammar varnish with its hint of clove and orange peel. Fine art hung on the walls of the studio: a Greg Curnoe abstract painting, watercolours by William Roberts and more. When I was 12 years old, my father taught me the process of properly sanding Masonite boards, and crosshatch-priming them with gesso. I used these lessons to prime Lewis’s boards.

My father and Lewis kept up a frequent correspondence. The earliest dated letters from Lewis to my father are from February 1966, but others have no dates or visible postmarks on the envelopes. They talked about many things, like whether her home was warm enough to endure the long winter, but my father never once attempted to influence her work.

In one letter, he asked whether Lewis would submit any of her paintings to the Expo 67 exhibition, which marked Canada’s Centennial. “No, I’m not putting anything into Expo 67, I haven’t the time to paint anything for it,” she replied. Lewis complained to my father that she had received over 300 letters after she was profiled on CBC TV on November 25, 1965.

“Maud was not a careerist, and she valued those friends, like Ontario painter John Kinnear who corresponded with her regularly, far more than an order from a premier or president,” writes historian Lance Woolaver in The Illuminated Life of Maud Lewis.

I remember walking to the post office to pick up the flat, brown-paper packages that Lewis mailed to us. She would send two or three—or occasionally five—paintings, and my father would post packages of five Masonite boards. He sold about 40 of Lewis’s paintings in London and the surrounding area for $24 each, sending Lewis some of the profits and using the rest to purchase her paints. He kept several paintings for his own private collection and gifted two of them to me.

The first painting depicted Lewis and her husband driving away from church in a black open-top Ford Model T during the summer, with Lewis wearing a bright red scarf. The second was a winter scene of children playing on the ice. Sadly, those two paintings were later stolen, but I like to think that the boards I sanded and primed with gesso, and the paints my father mailed to Lewis, will help preserve her art for future generations. But for me, working with my father was reward in itself.

When he learned of Lewis’s passing, he was filled with melancholy. “Maud was a beautiful woman, with a beautiful soul, and she painted from her heart,” I remember him saying. “The world has lost another underappreciated artist.”

The letters that Lewis wrote to my father were kept safe in an antique sea trunk that had once been in his studio. A few months before his death in 2003, my father and I opened the trunk together. I remember his smile as we recalled the days gone by, and the little old lady who painted pretty pictures.

© 2017, Sheila M. Kinnear. From “My Work for Maud Lewis,” Canadian Art (Fall 2017), canadianart.ca