How Ocean Researchers Are Figuring Out the Secrets of the White Shark

From social media to reality shows, here’s how ocean researchers are unravelling the mysteries of the world’s most notorious predator.

A white shark is human fear made flesh. It shears the water like a missile targeting its prey, with conveyor-belt rows of serrated teeth and skin so rough it was once used as sandpaper. From a primordial perspective, our fear of these creatures is understandable. But we’re a peculiar species, fascinated by what terrifies us. From Jaws to Shark Week, sharks occupy an intersection between terror and entrancement. So when one starts tweeting, of course we follow.

In March 2017, an American research group called Ocearch caught a 600-kilogram, 3.7-metre-long white shark off Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. They then bolted a flashlight-sized satellite transmitter to his dorsal fin and named him Hilton. That same month, they gave him a Twitter account run by a team of staff, volunteers and scientists. Thanks to Ocearch’s Global Shark Tracker app, anyone in the world could now watch Hilton’s migration as he swam (and tweeted) along Nova Scotia’s Atlantic coast.

With nearly 50,000 followers, Hilton is a minor celebrity and unofficial mascot to Nova Scotia’s shark fans. The staff at Ocearch use the Twitter account to present Hilton as a jaunty guy on the hunt for food and love. (A typical post goes, “Just gave the last fish a 15 second head start. Feelin’ sporty, I think I’ll give the next one 25 seconds.”) Hilton’s not the only social media star. Ocearch has launched 27 Twitter accounts for tagged sharks.

Thanks in part to its savvy marketing, Ocearch has become one of the best-known, and most controversial, ocean-research outfits in the world. (The name is a portmanteau of “ocean” and “research.”) At the non-profit’s helm is an equally polarizing figure named Chris Fischer. Instead of fearing sharks, he wants us to save them.

Fischer’s kingdom is the MV Ocearch, a 38-metre shark-research vessel. He speaks with a light Kentucky drawl and wears a hoodie and ball cap emblazoned with the logos of corporate sponsors. He often invokes Jacques Cousteau, the beloved filmmaker, television host and ocean adventurer, as the inspiration for Ocearch. But an obsession with disruption and growth makes Fischer more like a startup founder.

Fischer found his calling while working as the host of Offshore Adventures, a fishing show on ESPN 2. In 2005, as part of the show, he’d bring biologists on trips to help the crew catch fish for research. It was from those scientists that Fischer learned how ocean ecosystems could hinge on apex predators, such as white sharks.

Those sharks were in trouble from finning—the term for hunting sharks only to cut off their fins and dump them back in the ocean alive—and overfishing. Lose these balance keepers, the scientists argued, and the ecological webs around them collapse.

This inspired Fischer to turn his ship into a floating lab he eventually renamed the MV Ocearch. The boat became the base from which he filmed his shark-focused docuseries-meets-reality-television show, Expedition Great White, which premiered on National Geographic in 2010 (it was later relaunched as Shark Men and then again as Shark Wranglers). “I was just young enough and dumb enough,” he says, “that I set a noble goal to pour the world’s oceans into people’s lives on a scale not seen since Cousteau.”

Scientists have been analyzing white-shark populations since the 1970s in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, counting animals snagged as bycatch on longlines offshore and extrapolating those numbers to track population trends. But this method is imperfect, and it doesn’t account for sharks that stay closer to the coasts. Reliable population numbers for white sharks in this region are non-existent. That’s part of the reason why Ocearch and other researchers are instead focused on tagging: they’re trying to solve the bigger mystery of where white sharks are going and breeding. And, it was savvy of Ocearch to choose a predator that’s also a source of public fascination.

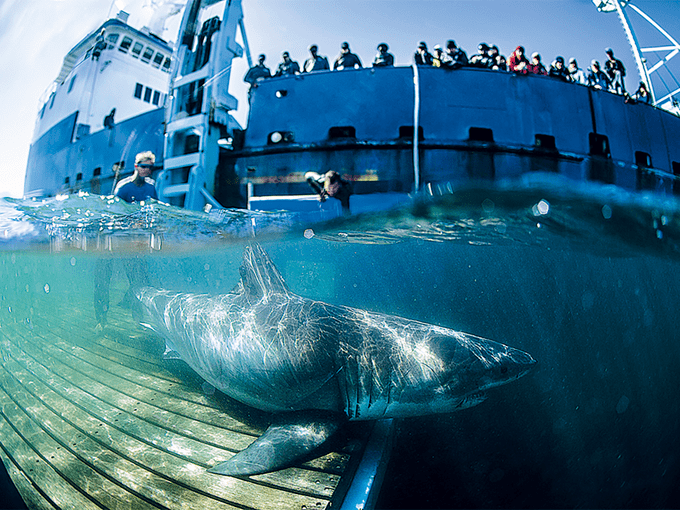

Ocearch’s tagging methods are unconventional, and that’s exactly why fans tuned in week after week to watch Fischer catch sharks on TV. Many researchers embed pop-up satellite archival (PSAT) and acoustic tags under a shark’s skin with a harpoon while it’s swimming or while it’s restrained along the side of a boat.

Instead of this method, Ocearch hooks the shark and lures it over to the ship and onto a specialized hydraulic lift. They then take samples, including blood, parasite and muscle. And in addition to the PSAT and acoustic tags, they bolt a smart-position and temperature-transmitting (SPOT) tag to its dorsal fin. By the time the shark is lowered back into the water, the SPOT tag is also pinging data to Ocearch’s app—and, soon after, a Twitter account.

Lifting a 500-plus-kilogram predator out of the ocean is inevitably a frenzied scene, and things didn’t always go smoothly. Shark Men, the precursor to Shark Wranglers, featured Fischer, his crew and shark biologist Michael Domeier, who advocated for taking sharks out of the water for SPOT tagging. The series seemed to exaggerate petty conflicts and dramatized the danger of working with white sharks.

In the first episode of the second season, the crew accidentally lodged a hook in the back of a shark’s mouth while tagging near the Farallon Islands, off San Francisco. Part of the hook remained lodged in place after the shark swam off, and a local marine sanctuary suspended Ocearch’s tagging permit until the organization altered its techniques—all while the cameras were rolling. Later in the episode, a stressed Domeier told Fischer that his professional reputation is on the line. “My name is on all these permits,” Domeier says. “You guys can go home and make a fishing show—I’m stuck with this mess.”

Other researchers called out Domeier for using such invasive tagging methods. Meanwhile Fischer earned a reputation as a maverick. Since the Farallon incident, Ocearch has stirred up controversy almost everywhere it has gone. It has been criticized for chumming—dumping large amounts of fish guts and blood into the ocean as a shark attractant. In South Africa, residents blamed Ocearch when a bodyboarder was killed by a shark near Cape Town (the city stated there was no evidence Ocearch’s chumming actually caused the attack).

Fischer’s second run on reality TV ended after four seasons and two years, but he concedes this was for the best. “You can’t get meetings with policy-makers and presidents if you’re the wacky guy on TV on Tuesday nights,” he says.

But leaving television also put his organization in a precarious financial situation, so he started selling sponsorships in exchange for “brand-integrated content.” In effect, Ocearch became a conservation group with an advertising arm. Today, the MV Ocearch is plastered with sponsors’ decals, including outdoor-recreation-gear brands.

Fischer has figured out a way to turn corporate money into funding for both scientific research and online entertainment for thousands of people. Ocearch knows that popularizing a single shark like Hilton means an audience is more likely to care about the larger issue. It also allows Ocearch to run a huge ship and buy the best equipment for scientists who work on the boat. And the more exciting the results those scientists produce, and the more people who are following their work, the more sponsorships Ocearch can attract to sustain future work.

The organization has made a point of emphasizing how it collaborates with the wider research community. Any scientist anywhere can access its app’s tracking data, for instance. Of course, scientists collaborate all the time. In December 2018, 46 researchers from all over the world released a paper laying out the work they all believe needs to be done in white-shark science. But none of that impresses Fischer.

“I’m talking about radical collaboration,” he says. “They’ve come together, and yes, they’re collaborating, but they have no scale.” He wants scientists all over the world sharing data with each other through Ocearch.

In mid–September 2018, Ocearch brought its bravado to Nova Scotia as part of its ongoing North Atlantic white shark study. It arrived on the province’s south shore with a permit from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (commonly known as the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, or DFO) to tag up to 20 white sharks. Ocearch anchored near Hirtle’s Beach, a swimming and surfing hotspot, and the LaHave Islands, popular with kayakers, snorkellers and scallop divers—and began chumming.

A man named Seth Congdon says that he and two friends were mackerel fishing when a crew member from Ocearch’s ship told them about a white shark they’d tagged. When Congdon joked that they’d been swimming nearby earlier that day, he says the crew member warned they’d been chumming pretty hard and recommended against going in the water.

Congdon’s friend and local surfer Jefferson Muise was especially troubled and went to CBC when neither Ocearch nor the DFO got back to him with answers. The community suddenly realized how little it knew about Ocearch’s operation. Ocearch’s then-chief science adviser (he is now the chief scientist), Bob Hueter, responded by telling a community newspaper that the account was a “complete fabrication; never happened.”

Muise isn’t naive. He knows that in the summer and fall, when he’s out in the waves, he’s sharing the water with white sharks. But he’s also not wrong to be concerned. While scientists are still debating whether chumming could endanger people close to shore by altering shark behaviour, it’s not something many other researchers are willing to risk.

Heather Bowlby, head of the DFO’s Canadian Atlantic Shark Research Lab, travels at least three nautical miles offshore when baiting for white sharks. (She also notes that, unlike chumming, with baiting, fish is placed on a hook to lure an animal. She also says she doesn’t chum at all for white sharks.)

And Chris Lowe, the director of the Shark Lab at California State University, Long Beach, who regularly tags sharks off the coast of Los Angeles, says, “There’s no way I’m going to chum or bait along a public beach.”

Fischer dismisses the criticism. In his mind, any biologist not interested in working with Ocearch is a selfish data hoarder who is more interested in getting ahead than saving sharks. “We had to totally disrupt the whole way science was done,” he says. “If you really look at any of them, they all have different agendas. It has nothing to do with sharks.”

Tell that to biologists who have dedicated their lives to this work and you’ll get a different opinion. Lowe says Ocearch isn’t so avant-garde but, rather, at its core, is a scientific lab like any other. The only difference is that its facilities are mobile, allowing it to flit from location to location—armed with cameras and corporate sponsors and Twitter accounts—leaving resentment in its wake.

As of this past spring, Ocearch was still tagging and tracking sharks around the world, and touting “#factsoverfear.” But Hilton the white shark’s Twitter account has been silent since August 2020. Ocearch had lost track of him. The pings from his transmitter had gone silent.

© 2019, Chelsea Murray. From “Twitter Sharks,” The Walrus (June 3, 2019), thewalrus.ca

Next, find out if sharks really do smell blood.