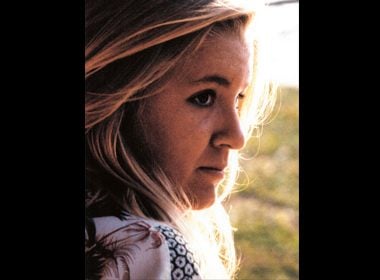

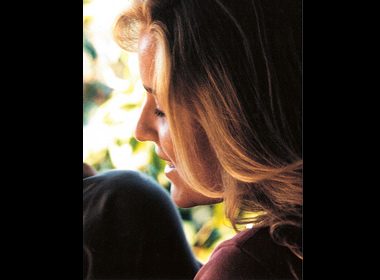

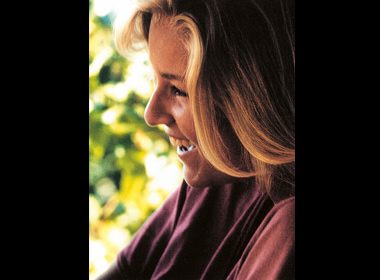

Erin Glimour could stop traffic for the usual reasons. Tall, stylish and slender, with long waves of sun-streaked blond hair and fine, elegant features, she was, by all accounts, spectacular. Still more arresting was her personality: she was warm, funny, intelligent and kind. And on an ice-cold, wet and windy night in Toronto in December of 1983, an unknown assailant raped, bound and killed her. She died when a knife pierced her good heart.

The knife was never found.

What makes Erin’s murder so compelling after all this time? There are thousands of cold cases on file in Canada, dating back to 1956. But her father is David Gilmour, a well-known billionaire entrepreneur; her mother, a ballet dancer and legendary beauty. Erin, at 22, seemed destined to excel at fashion design and journalism, which she loved-at anything she chose to do.

Her case is cold, yet details of the murder continue to be resuscitated. In 2000, the DNA from the crime scene at her Hazelton Avenue apartment-where Erin lived alone-was matched to another homicide that took place the same year.

In August of 1983, Susan O’Hara Tice, a lovely, dark-haired 45-year-old mother of four who worked with disadvantaged children, was attacked and killed in her Grace Street house. A neighbour is said, according to Canadian crime writer Lee Mellor, to have heard her screams and done nothing. The only connection between the two women is the awful details of their deaths and that they lived alone (Tice was separated from her husband at the time).

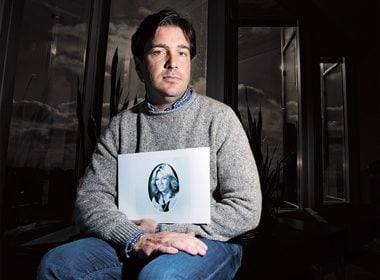

Many new stories appeared at the time, and again in 2008, police were reported to be “tantalizingly close” to solving the crime. But no arrest ensued. In December of 2012, Erin’s family put up a $200,000 reward for information leading to the arrest of the killer. This figure is augmented by the $50,000 the police are also offering.

Erin is described by those who knew her best as magnetic. And so is her tragic story, which remains, for her family, unfinished and unavenged.

The day after Erin was murdered, her mother, Anna McCowan Johnson, and stepfather, Donald Johnson, had the devastating task of telling the stepbrothers she adored, Sean and Kaelin McCowan, then 13 and 11, the monstrous news. Sean put his fist through a wall. “He is still very angry,” his brother, Kaelin, tells me. “The hole stayed in that wall for years.”

The hole in the wall is, of course, the perfect symbol of Sean’s enraged sense of the murder. As I talk to some of Erin’s family and friends, Sean emerges more, each time, as the central crusader. He speaks for most of the family, especially for his mother, who cannot. She and her daughter were very much alike and best friends.

While everyone who knew Erin wants justice, some have made peace: Kaelin saw a therapist five years ago to work through the trauma. His entire childhood, he says, was erased by the “confusing, unreal” news of his sister’s death. He has since “found peace” and even forgives the killer, because capturing him “would serve no purpose.”

“The damage is done,” he says, his voice breaking. “And I do not believe Erin would want retribution,” he adds, remembering the kind and caring sister who once spent a night helping him construct a project about Egypt and bought him a Swiss Army knife, which he still cherishes and which cut his hand the day he received it.

The wall, the cut: these are emblems of the damage left by what the English writer Walter De La Mare calls “the blow.” “God has mercifully ordered that the human brain works slowly,” he writes, so that shock and pain register in degrees and over time.

Sean is also a sweet and soft-spoken man. I talk to him about Erin while he takes a break at Cormark Securities in Toronto, where he is the director and a CFA. He tells me about the sister who spent “tons and tons of time” with him.

He talks about her great sense of humour and her quirky taste-vintage clothing and Donna Karan, David Bowie and Lionel Richie. Then he laughs. “She would probably be embarrassed about the Lionel Richie now.” Finding the killer would “close a loop,” he tells me. And getting more information out there about her may trigger someone’s memory.

“What do you miss about her?” I ask.

Sean cannot speak for the tears. He misses that she will never meet his four children. He misses talking to her and getting advice, as he so often did when he was having a hard time at school. It is a wound that never heals.

Sean wants that name.

“We just need one name.”

This is Steve Ryan, who heads up the Toronto police’s cold-case squad, talking about the man who murdered Erin Gilmour 30 years ago this past December. He feels particularly hopeful about the case, given their possession of the DNA material. He has a hunch. “Somebody suspects,” he tells me. Somebody knows who did this. And would that someone please call him, at 416-808-7408? You don’t even have to leave your name.

Justice is not David Gilmour’s concern. The brilliant entrepreneurial mind behind Fiji Water-and now Wakaya Perfection, an organic-ginger company-who was once told by celebrity astrologist Jeane Dixon he would play a strong role in the last pure place in the world, tells me he is not interested in salacious crime stories. Or justice. “Looking for justice is wasted energy,” he says.

So what is critical? “Stop the next tragedy.”

“Vengeance doesn’t change a damn thing,” David says. His voice is tender, his manner kind.

His new passion is health and wellness, but his most constant and rigorous belief emerges from his ongoing tribute to the daughter who appeared to him in a vision shortly after her death. He had been wallowing in grief, he says, drinking vodka and swallowing Valium-committing a slow, unthinking suicide.

Erin came to him as he slept and said, “Daddy, don’t you love me?” She was as clear as day.

“Of course, I do,” he said. “Can’t you see what I’m going through?”

“That’s what I mean,” she said. “Do something to make us proud of you.”

David discarded his pills and did just that. He built a chapel on Wakaya, the island he owns in the South Pacific. A dedication to Erin is engraved there, and an image of her as a little girl is soldered into the stained glass. He built a school for the blind in her name in the Bahamas, as Erin had been horrified to learn the ways in which the blind were stigmatized in parts of Nassau.

And David and his wife, Jill, founded and continue to create schools for preschoolers. These preschools for early care and education are located in rough areas of the United States and Fiji, among other countries, and David believes they play a significant role in reducing crime.

“Bad things begin at this age, three to five,” he says. “Bitterness at the power structure, bullying, the persuasive idea that everyone is wrong-the tools for killers in training.”

This is a significant part of the legacy Erin leaves behind. Still, her father misses her every day. “She was an extraordinarily caring girl,” he says. She looked out for friends in need.

If he could talk to her today? David’s voice falters. “I would thank her,” he says, “for changing a great part of my life and what I do.”

“I just want to know why,” says Judith Tatar, one of Erin’s best friends. She is speaking from a quiet space before leaving for work at her art consulting business, lost in a memory of herself and Erin on a vacation with David Gilmour, driving along the Long Island coast in a CJ-7 Jeep with the top down, blaring Billy Joel.

“She and David would short-sheet each other’s beds,” Tatar tells me and laughs at the memory of her friend who loved dancing, mischief, Asian food, Spanish culture and taking pictures with the Nikon she carried everywhere. But she was introspective, too. A deep thinker who was preoccupied with injustice, she always went out of her way to extend love.

On Christmas day in 1983, the day after Erin was buried, one lone present remained under the tree after the others were opened: a sweater Tatar had admired. This makes her cry, after all these years, about her kind friend whose absence leaves a “hole that can never be filled.” If Tatar could talk to her again, just once, she would ask her, “Erin, where have you been? Everyone’s been looking for you.”

Erin and her friend Karen O’Connor used to run around The Bishop Strachan School in matching engineer overalls and raccoon coats. “Erin had so many close friends,” she tells me. They all gravitated to her cool rec-room parties and her kitchen, where her striking and glamorous mother held court, dispensing food and advice, and attracting, like her daughter, flurries of besotted young men.

“It is the biggest catastrophe of my life,” says O’Connor, who works on Wall Street. Like everyone I speak to, she emphasizes Erin’s creativity, flair, popularity and sweetness. They were “Erin and Karen.” She often forgets Erin is dead and thinks of something to ask or tell her friend. Her friend who mixed Smarties into her movie-theatre popcorn. Which O’Connor does, every time, to this day.

When the unknown, sadistic killer took Erin Gilmour’s life, he took everything. He took away the children she would surely have had, as she loved them. Her brothers are painfully sad on this subject. They have seven children between them, and Kaelin’s oldest daughter, 11, is a sensitive girl who is now trying to come to terms herself with the loss of the beloved woman she never met. They will visit the chapel on Wakaya soon and see Erin’s face in the coloured glass.

Sean, in the meantime, will keep looking and hoping that one day someone will come forward-that any day now, one brave person will pick up the phone and end the dreadful suspense for this big, beautiful and broken family.