This After-School Program Challenges Toxic Guy Culture

Through basketball, Next Gen Men gets boys talking, both on and off the court.

For boys, messages about who they should be and how they should behave arrive early and remain insistent: Man up. Grow a pair. Don’t be so gay. The result is that being a young man oftentimes means trading off tenderness and connection for social status and approval.

Jake Stika, the 34-year-old executive director and co-founder of Next Gen Men, a non-profit focused on redefining masculinity for boys and men, knows this dynamic well. Back in 2007, during his second year at Brock University, Stika struggled with depression. To cope, he began binge drinking. Soon, he was getting into fights. At the same time, his friend Jermal Alleyne Jones was grieving the loss of his younger brother, who had been bullied and died of suicide. Together, and in conversations with friends, they realized just how toxic traditional ideas of masculinity could be for boys’ mental health.

“We wanted something different for the next generation,” says Stika. He, Alleyne Jones and another friend started Next Gen Men in 2014, beginning with a 10-week after-school program in the Greater Toronto Area. It landed on a simple but effective formula. Along with a recreational activity, like basketball or cards, the boys have facilitated conversations about gender equality, homophobia, bullying, mental health and healthy friendships.

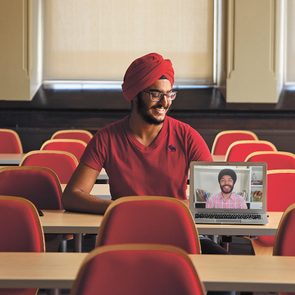

“There is a myth that boys and men don’t want to open up about their feelings,”says Stika.“The truth is they aren’t invited to have these conversations.” One of the key lessons from these early groups, he adds, was that boys were eager to talk. Pre-pandemic, Next Gen Men offered after-school programs across the GTA, facilitated by youth program manager Jonathon Reed. The programming has since moved online. Stika estimates that more than 2,300 boys have participated.

Twelve-year-old Mateo is a current participant. Another boy had felt picked on by Mateo and asked Reed to invite him to join the program. Mateo agreed and the two worked through their conflict by having conversations both individually with Reed and together. The boys have since become “pretty close” friends, says Mateo, bonding over games like Fortnite and Minecraft. For Mateo, it was also a chance at a fresh start. He liked that Reed didn’t judge him. “Jonathon didn’t think I was bad,” he says, “just that I could do better.”

That kind of individual transformation is a central pillar of NGM’s work: to support boys in building empathy and in learning to communicate and care for themselves and one another. Most participants are between ages 11 and 14—research indicates that adolescence is when children form their own values and identities. It’s also when there is often a rise in bullying, racism, misogyny and homophobia in social interactions.

“There are narratives in media and culture that boys have power, or will have it. But when you’re 12, you don’t feel you have power,” Stika says. “So often boys enact what little power they have through differentiation,” that is, by picking on others and jockeying for social status. NGM disrupts this by offering alternative, healthier versions of masculinity. And their work doesn’t stop after a certain age, either.

Shortly after NGM started, Stika’s friends told him they wished they had groups like his when they were kids. In response, NGM began hosting gatherings for adults of all genders. More than 2,000 people have since participated across five Canadian cities, including Calgary, Edmonton and Vancouver. This year, NGM plans to get even bigger and will soon start a development program for educators called Next Gen Mentors. For Reed, it’s all part of a revolution: “What could it look like for this light bulb moment not just to happen for one boy, but for a whole community?”

Find, out out how a Toronto-based charity uses art to fight homelessness.