How the North Invented the Science of Parkas

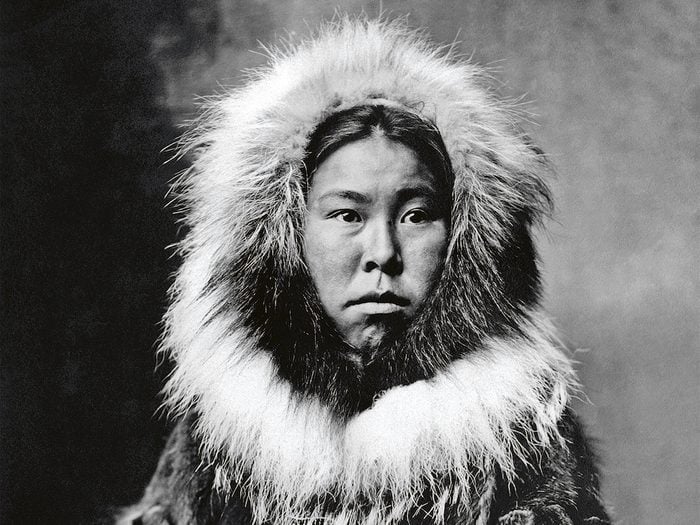

A brief history of the world's warmest coat, and the Indigenous people who are keeping the tradition alive today.

Shawna Dias’s sewing machine is barely visible on her work table behind racks of fur. Hot pink, bright yellow, baby blue, the furs hang like a fluffy rainbow. In the space of about a day, she can transform them into custom-made parkas at her Rankin Inlet home. “When I first started, I didn’t think it was going to be a business type of thing. I didn’t realize they were going to get so popular,” she says. To be fair, Dias was 12 when she first learned to sew coats, watching her mother stitch. Today, she’s one of the most popular parka makers in the Kivalliq, (the southwestern part of Nunavut), with a lively Facebook page, Dias Designs, and a waiting list in the triple digits for custom orders.

She’s not sure how many coats she sews in a year, but her niece counted the parkas on her Facebook page, and says she made around 200 in six months. They don’t all stay in Nunavut either, where custom-made parkas are common. She takes orders from all over Canada and even the United States. Dias creates her own patterns, based on people’s measurements or, if they’re local, their body shape.

“Everyone’s got a different body shape, so it’s so much easier freehand cutting out a coat for somebody,” she says. “It’s what we grew up with, so it’s just what we use. Well, that’s what I have used because of how my mother used to make them. She was born in 1929, and began sewing when she was young, too. So, old patterns!”

Parkas have existed for centuries. And now the world is learning what northerners have always known: if you want to stay warm, there’s nothing better than a northern parka.

Hot history

The Kitikmeot Heritage Society features rows of parkas, standing like sentinels through time. Its Patterns of Change exhibit includes examples of Inuinnait parkas from over 150 years, made by dozens of different community members. Pamela Gross, executive director of the Kitikmeot Heritage Society, says, “The exhibit celebrates how ingenious our people were to create garments that were very beautiful, finely made and resourceful.” Displayed parkas include traditional styles made from caribou, the Mother Hubbard style with ruffled hem and cuffs, and modern coats featuring brightly dyed seal skin that are, as Gross says, “traditional with a twist.”

Those garments are written over with history, Gross says, with changes expressing major events in the lives of northern peoples—not all of them good, but each influencing the living culture and what people wore. First contact with Europeans, for example, brought new materials such as calico and wool to the Arctic. Parkas changed in both shape and style through the Cold War’s Distant Early Warning Line era, when military styles and fabrics arrived. And many parka makers from different parts of the North exchanged techniques when they were forced to attend residential schools, swapping tips on floral embroidery styles and other regional techniques.

Gross says determining the origins of each stylistic change was a project in itself. It’s hard to pin down, even today, exactly why individual parka styles are preferred in each region of the North. Some of it has to do with what people are doing while wearing the parkas, some of it has to do with traditional patterns, but a lot of it comes down to the styles and preferences of the individual seamstresses.

Details of the parkas—like whether the sleeves are curved or straight, the length of the garment and how fitted it is—often come down to preference and trend. For instance, many of the men’s parkas Dias makes are shorter, with elastic at the wrists and hem. In the Baffin region, they tend to be longer. She’s not quite sure why, whether it’s just the fashion or if the style is dictated by the specific activity (for instance, hunting parkas are generally pullovers, because zippers may freeze to the wearer). She, like many seamstresses, adapts to what her customers need.

“That’s why it’s so hard to explain the different shapes of the coats or how they’re sewn,” says Dias. She tends to favour fitted parkas herself, with delicate lines and vibrant materials. You can spot one of her creations by the lace she incorporates into her designs. “My mother never used to use stuff like that.”

Cultural comeback

One territory over, tucked away in the underbelly of the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre in Yellowknife, NWT are even more parkas, some snuggled in the freezer to protect their fur. Karen Wright-Fraser flips over the hem of one to show the underside of the embroidered trim, where the tiny stitches that went into creating this example of Delta Braid, a type of ribbon trim from the Beaufort Delta region made from layers of bias tape and seam bindings in geometric patterns, are barely visible. Wright-Fraser is the former community liaison coordinator at the museum and also a seamstress. “The techniques were pretty much forgotten,” she says.

That’s now changing. Over the past several years, she’s seen an upswing of people learning the skills of their grandmothers, particularly as parkas become a popular fashion item on social media. “A lot of young people weren’t interested before. Now I notice a lot of them are going to their grannies and learning,” she says. They have pride. Even more are learning online and going to online groups for support and help. “There are so many different ways. Then you choose the way that works for you. You’re finding your own path.”

She pulls out another coat, this one a vibrant red with shiny, smooth embroidered flowers. “Isn’t it beautiful? That’s skill. It looks like it was done on a machine, but it’s by hand,” she says, pointing out the middle of each flower, decorated with dozens of French knots, made from embroidery floss. “People learned this from the nuns. Before that, we used to use moose hair and seed beads. People would use porcupine quills to sew geometric designs. Then the floral things came from the nuns.”

That’s what distinguishes many Dene or Gwich’in parkas: the beautiful embroidery dancing across the hems, the yokes and the cuffs. Many examples came out of the Inuvik Sewing Centre, which from the 1960s to the 1980s brought Indigenous women together in a co-operative to produce parkas for commercial sale. Such parkas often feature intricate Delta Braid and appliquéd fabric figures. Those coats can still be spotted today, with their signature Inuvik tag stitched into the collar. Even more exquisite work can be seen on Spence Bay parkas, produced by women in what is now Taloyoak, Nunavut.

No matter the style, the time dedicated to making something useful and beautiful is a way to show respect and mark your family as good providers. Even today, when people have nine-to-five jobs and free time is scarce, wearing a handmade item carries a different value than just buying it from a store. “There’s more to it than just walking around with a beautiful parka,” says Wright-Fraser. “It was made with absolute love.”

Science of survival

In fact, parkas may have been what kept our species alive. Mark Collard, a professor at Simon Fraser University, proposes that Neanderthals died out because they didn’t have specialized cold-weather clothing. He and his grad students studied the bones of animals left behind at ancient sites inhabited by both early modern humans and Neanderthals and concluded that such animals as rabbits, foxes, wolves and wolverines were likely used as a source of fur, rather than food, for early modern humans. Bone needles and other evidence at the sites also suggest early modern humans were tanning hides and creating fitted cold-weather garments, while Neanderthals were donning, at best, simple cape-like garments.

It helps explain why even though other studies have found that the bodies of early modern humans seemed to have been adapted more for tropical conditions, they still outlived Neanderthals—whose stout bodies and short limbs evolved for more glacial conditions. In addition to protecting from frostbite and hypothermia, parkas would have allowed for a greater range of hunting and gathering and longer stays on the land, which would have increased the chances of not just survival, but the opportunity to thrive.

And while parka materials may have changed over time, the science of keeping warm has not. “The traditional clothing system developed and used by the Inuit is the most effective cold-weather clothing developed to date,” concluded a 2004 study published in Climate Research on the effect of Inuit fur parka ruffs on facial heat transfer. The study placed sunburst-style parka hoods into a wind tunnel to see what happens under extreme temperatures. In the wind, friction forms a collision of molecules next to the skin called the boundary layer. This layer insulates the skin. The study found that natural fur creates a thicker boundary layer by changing how air flows across the face. Of all the designs, the sunburst style proved one of the most effective.

Natural fur has hairs in a variety of lengths, changing how the air flows and protecting you even more. The most effective fur for this, according to the study? Wolverine, which surprises no one making parkas. Wolverine, which easily sheds ice and frost, has long been used to trim hoods in the North, alongside wolf, fox and other animals. “It’s so much warmer! I had a fake fur coat once. You’ll just freeze your face with that,” says Dias.

As frequently as you’ll see custom-made parkas in the North, the streets of Yellowknife, Whitehorse and Iqaluit are also filled with the ubiquitous Canada Goose. But the company is paying attention to those traditional-inspired designs. In 2019, Canada Goose launched Project Atigi (the Inuktitut word for parka) with the first round of 14 seamstresses from four Inuit regions—Inuvialuit, Nunatsiavut, Nunavut and Nunavik—creating parkas using Canada Goose materials. Part two, launched in January 2020, showcases 90 parkas made by 18 designers, each commissioned to create a collection of five pieces. Proceeds from sales of each parka will go to Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the national organization protecting and advocating for the rights and interests of Inuit in Canada.

While some saw the move as appropriation of Inuit culture, others saw it as an opportunity for appreciation outside of the Arctic. Gross, for one, says it’s a good thing when southerners see the talents of northern seamstresses. “There are a lot of people who still think of us as ‘Eskimos,’ people who live out in iglus,” she says, adding, “This is something we can hopefully change through talking and sharing who we are through our culture. It’s something people should be proud of.”

© 2019, Jessica Davey-Quantick. From “Art and Science of Staying Warm,” Up Here (December 2019), uphere.ca