How I Survived A Parachute Malfunction—1,200 Metres Up!

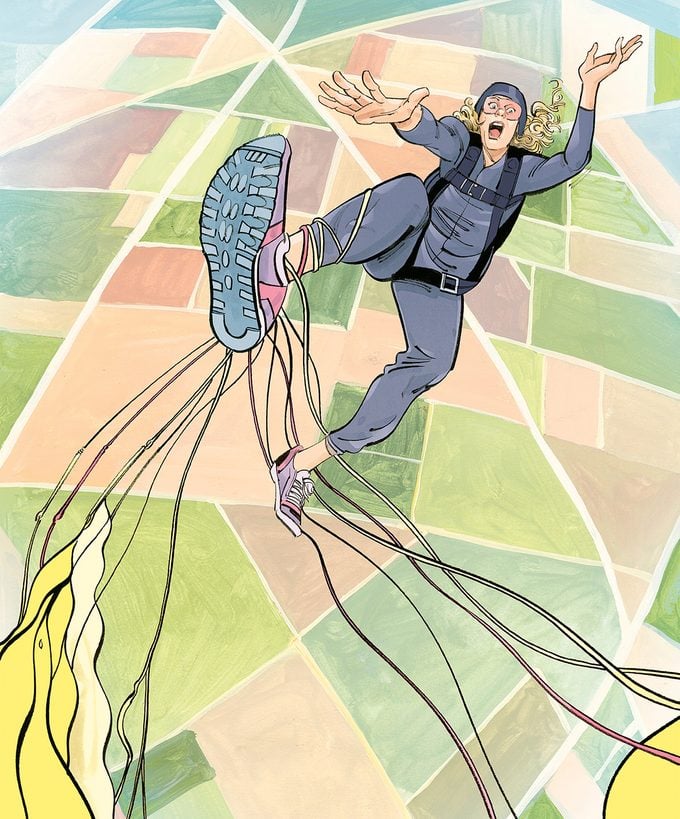

With the ground below her rapidly coming closer and the parachute wrapped around her leg, skydiver Jordan Hatmaker prepared to crash.

November 14, 2021, was a perfect day for skydiving: sunny, with little wind. I was a novice solo jumper; I’d jumped only 14 times before, not enough to be licensed. It scared me, for sure, but a little fear always makes you a better risk taker, right? That’s what drew me to skydiving in the first place. I’ve always been extreme.

It took about 40 minutes to drive from my home to the hangar outside Suffolk, Virginia; it was in an area with lots of empty land and airspace.

I went up in the plane with a group of about 15 for a first jump at around 1:30 p.m., and it was beautiful. From the start, I went through the safety procedures with my coach that day—a ritual you do for every jump, no matter how much jumping experience you have had. This includes pointing from the plane door to the drop zone—where you land—4,100 metres below, so you can direct your jump.

Then we jumped; me first, then my coach. We were in freefall at some 200 kilometres an hour, descending about 300 metres every five seconds. It was exhilarating and terrifying all at once, with the world opening up before me, coming into focus in mere seconds, even though it felt a lot longer.

The wind eddies carried me for the freefall. At about 1,200 metres, I deployed my pilot chute—the small parachute used to extract the main one. After the main chute was released and inflated, I had about a minute to enjoy the peace and quiet as I floated gently to the ground, the grass quickly coming into focus. I felt invincible.

Not long after, we went up again for a second jump. The mood on the plane was light: lots of joking, lots of laughing. My coach and I went through the same safety routine, then we jumped.

After 30 seconds, at around 1,680 metres, we tracked away from each other because you need lots of empty space to safely deploy your parachute. I looked at my altimeter and realized I was lower than I’d thought. The ground was coming up so fast! I knew I had to pull the pilot chute at roughly 1,200 metres, like I’d done the last time, but I was caught off guard and rushed to pull my chute without taking the time to stabilize my body position. When I pulled it, instead of releasing into the airstream to inflate, the pilot chute wrapped around my right leg.

The chute was pulling my right leg up like a ballerina’s, while the main parachute remained in its bag. Just get it off, I told myself calmly. I wasted about seven seconds trying—unsuccessfully—to get untangled; I should have opened the reserve chute right away. (It’s a backup for when the main one isn’t working.)

With the ground rapidly coming into focus below me, I prepared to crash. I didn’t think it would be a catastrophic impact. Maybe I’ll break a leg, I thought. I’ve always been an optimist.

Then, suddenly, the reserve parachute opened. I managed to gain some control, steering myself toward some grass, hoping for a softer landing.

I had just a few seconds to feel some relief. Then the main parachute released from its bag. It inflated, and the two parachutes began pulling in opposite directions, causing me to accelerate hard and fast toward the ground, not far from the drop zone.

When I crashed, my body felt like it was on fire. I tried to get up because that’s what you’re supposed to do if you don’t land on your feet, to show you’re okay. But I couldn’t. I couldn’t move anything below my waist. So I lay there, my face in the grass, my arms flung out to either side, and I screamed. “Please, somebody help!” In between calling for help, I prayed out loud: “Please, God, don’t let me be paralyzed.”

I lay with my face buried in the grass, fully conscious, for about five minutes before people from the skydiving club got there. They quickly surrounded me, eager to help, but there was nothing they could do. It was too risky to move me before the paramedics arrived. But I didn’t understand that yet, and they had to listen to me swearing and yelling at them to help me as the shock wore off and the pain really set in.

When the first two paramedics arrived by ambulance, half an hour later, they tried to move me onto a board for transport, but it hurt so much, I screamed. Then I heard the helicopter.

The air-ambulance crew came equipped with ketamine, which sent me to la-la land, and I was transported to the nearest trauma centre.

In the end, my injuries were pretty intense: a shattered ankle, broken shin and a spinal injury that caused a spinal-fluid leak. No one could tell me if I would walk again, but I was determined. In February 2022, just three months after the crash, I walked again for the first time. I began a heavy course of physiotherapy that I’m still doing. But, after being unable to lift my legs because of the accident, last November I was actually able to climb to Everest base camp.

Oh, and I plan to skydive again—only I haven’t told my parents yet.

Next, check out this true story about a woman who became trapped in her car during a “snownado.”