I’d Never Had a Personal Connection to Remembrance Day—Until I Discovered One Soldier’s Death Certificate

My quest to learn the story of Mervyn Naish, a First World War soldier, started when I found his 1917 death certificate inside an antique buffet.

It’s odd sometimes how we make connections with the living and the dead. One of the most striking I made was with First World War soldier Mervyn Naish in 1987, when my wife bought an antique dining room buffet at an auction in Barrie, Ontario, some 70 years after he died.

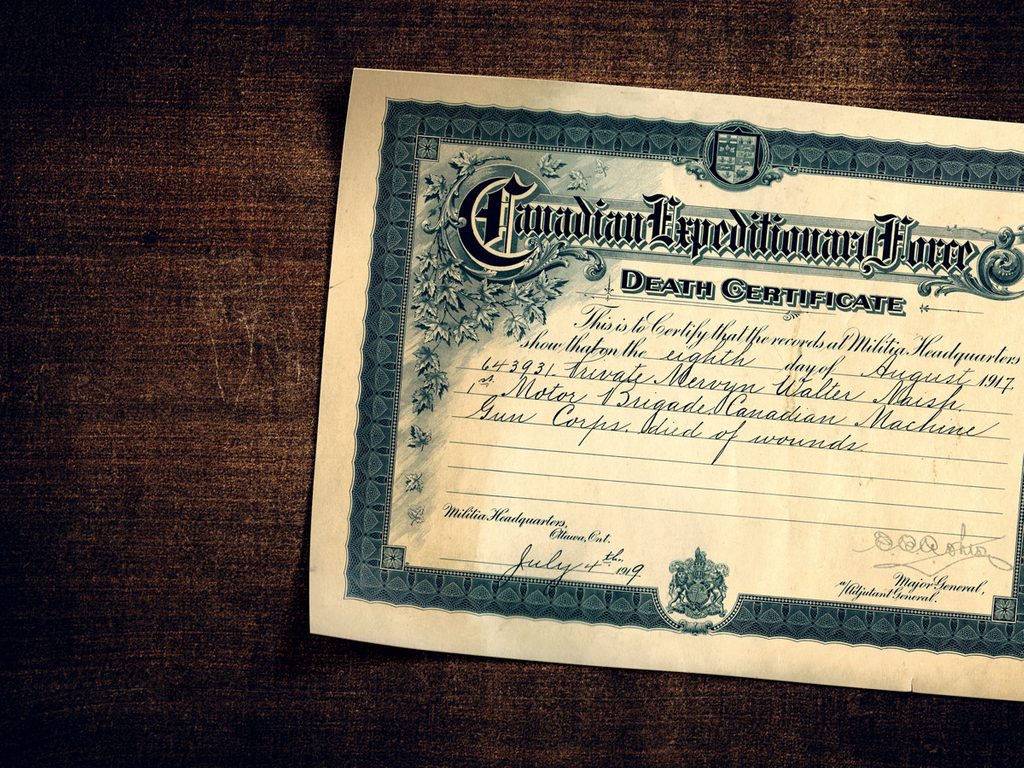

A week or so after she brought it home, it still sat in the garage. When I examined it, I noticed a document lodged at the back of one of the drawers. The paper was yellowed with age, the same colour as the wood, and might have been easily missed.

I retrieved what turned out to be an original Canadian Expeditionary Force death certificate for Mervyn Naish of the 1st Canadian Motor Machine Gun Brigade. The certificate, dated 1917, was rather ornate, not large, maybe 20 by 30 centimetres, with the details written in fountain pen. I held it carefully because I was holding a piece of history that I knew didn’t belong to me. Mervyn had died of his wounds, which means he likely suffered before he expired. I knew I had to return this certificate to someone connected with the fallen soldier.

I began by checking the war memorials in Simcoe County, just north of Toronto, not far from where the auction was held. The area is full of small cities and towns. As a lawyer, I often attended satellite courts throughout the county, and on my way home I would check each town’s memorial. I had never before scanned the long, sad lists of names carved in stone, and the experience was sobering. Each one had been a man who was someone’s son, or brother or husband.

Mervyn Naish, however, was not one of the names I found. He was proving to be elusive.

Finding Mervyn

Discouraged by my lack of success, I lost interest for a few months. But one rainy morning I was racing to court in Penetanguishene, Ontario, when I spotted a memorial in the village of Waverley, which I hadn’t seen before. I stopped on my way back and scanned the list of casualties.

Among the fallen soldiers of Medonte township was the name Mervyn Nash. Although the spelling of his surname was different, I felt sure that this was the right man. Later that day I checked the phone book for the area and came across another Mervyn Nash. I didn’t believe it at first. I reread the entry several times. I felt a mixture of shock and relief, as I knew this must be the family.

Instead of calling the number, I decided I would just drive the certificate over to them.

The following Saturday, I placed the certificate in a legal file folder and headed to the township where Mervyn Nash lived. It was a sunny spring morning. I stopped at a variety store and asked the fellow behind the counter if he knew Mervyn Nash. He did, and gave me directions to his farm.

As I turned into the yard, I realized I’d been looking forward to this moment. I walked up to the house and could see someone at the kitchen table through the screen door. I knocked.

The middle-aged man stood up and I could see he was dressed as if he’d just come in from working outside. He was wary of this stranger at his door.

“Are you Mervyn Nash?”

When he said yes, I pulled out the document and handed it over. “I think this belongs to you.”

I watched him mouth the words as he read, and when he looked at me, he was overcome, unable to say much except that he wanted to know who I was and how I had come into possession of this certificate. I explained my story, then asked him for Mervyn’s.

A Walk Through History

The man I was speaking to had been born about a decade after the end of the First World War and named in honour of his fallen uncle. Uncle Mervyn had enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in Orillia, Ontario, in February 1916. Because he was underage, he used a false name and date of birth. The soldier died in Noeux-les-Mines, France, a year and a half later, on August 8, 1917.

Mervyn brought me inside and showed me his uncle’s photograph taken shortly after his enlistment. Mervyn had been entrusted with the soldier’s medals and postcards but had never seen the death certificate.

Mervyn and I spent the morning together. We walked around the farm, noting where the Coldwater River flowed through and where the salmon came in from Georgian Bay to spawn. Everything was green and lush—a beautiful and tranquil setting. While we spoke, we both thought of the young soldier who had been born and raised in Creighton, Ontario, and who had never returned from the war. Every few moments the conversation would naturally return to him. I asked Mervyn about the misspelling of the last name and was told that it actually had a significance of its own.

Back at the house, Mervyn showed me old family records he kept hidden away in a bible and explained to me that the family name was once spelled Naish. It was changed to Nash a few decades after the family had immigrated to Canada from England in the 1830s. The young soldier had used his old surname in order to get around the local recruiters, who would have known the Nash family and that Mervyn was underage.

Before I knew of Mervyn Naish, Remembrance Day was never personal. I never had a relative killed in any war. But every November 11th since then I have thought of him during the minute of silence and when the bugle is sounded. I imagine that he, like many others, was a boy in a hurry to get off the farm, into a uniform and off to Europe, before all the excitement ended. I have thought of the sorrow that would have befallen his family when they received word of his death. I can only think that this certificate was too painful to look at or to hold, and so became lost in a hidden part of a drawer, and then forgotten with the passage of time.

But this is one young soldier’s story that needs to be remembered.

© 2018, Michael Shain. From “Remembrance Day Was Never Personal. Then I Learned About Mervyn Naish,” from The Globe and Mail, (November 4, 2018), theglobeandmail.com.

Next, check out 30 powerful Remembrance Day stories from Canadian veterans.