What Reuniting With My Childhood Best Friend 20 Years Later Taught Me

After decades of not seeing my childhood best friend, we finally talked about that terrible night from so long ago. Here's how one conversation changed our lives forever.

Hello Meryl. This is my best 60th birthday present. Long time no see. xx Cathrin

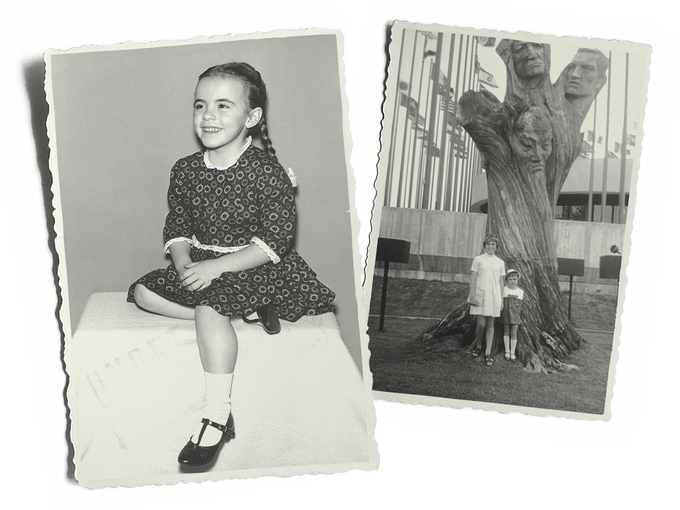

I tapped my note to Meryl the same night she sent me a birthday text. It was our first communication, I should mention, in 20 years. We’d met as schoolgirls when we were six and were each other’s first friend. It wasn’t that we’d meant to drift apart—it was just life, really—but after so many years the silence between us had become too deep to breach. This birthday text was momentous, in other words. Let’s call it Stage One of the reunification.

The temperature outside my Toronto house had nosedived to -18 C. It was the kind of night when Meryl and I, at 12 or 13, might have gone out for an epic winter adventure, leaping over the ice hills that rimmed the shore of Lake Ontario. Newly 60, that sounded like at least one broken hip. Meryl wrote back within minutes, and we were off.

I thought about the first time I saw Meryl across a paved schoolyard in Grimsby, Ont., our hometown. (I’ve changed Meryl’s name, at her request, for this story.) She was dark-eyed and watchful, like me, and it was like recognizing something important in myself. Meryl, in her first text back, suggested we meet in the real world, but that felt a bit hasty. Sometimes I didn’t think about Meryl at all, sometimes I thought about her a lot, but the one constant was that she was safely situated in the past. This one-text-away Meryl was very present, and I proceeded with caution.

As we texted back and forth over the next few days, Meryl was the first to relax into randomness, describing a bird or tree outside the window of her home, or remembering some old boyfriend or other. We lingered on the soft pillow of nostalgia but didn’t smother ourselves with it.

The memory-syncing part was cool and mysterious. When Meryl mentioned the Tea Room on top of the Grimsby escarpment, a rickety stick building suddenly appeared in my mind. It was made of logs, wrote Meryl, and the Tea Room stopped wobbling. Giving it shape together made our memories, if not free of falsehood—we both tilted toward the positive—then at least real. The magnificent magnolia tree at Livingston and Main needed no prompting: Big! Bold! Pink! But more satisfying than putting Grimsby back together again was that Meryl’s memories made my version of things less dubious. It had been a long time, if ever, since I’d felt that I was a reliable keeper of the past.

We caught up on our adult lives, too, as we texted back and forth. She still worked as a florist, as she had when we’d last spoken. And she’d stayed in the same Ontario town she’d moved to when she married, and raised her three daughters there. Still in the same house, it is now yellow.

Our moms were a steady topic. They were both 91 and both living. Or, to put it another way, they were both 91 and both dying. My mom had just lost the part of her mind that would have remembered our childhood, while Vivian was in her right mind but couldn’t talk properly after a recent stroke affected her speech. Our mothers’ connection to each other, separate from Meryl and me, was mostly invisible to us growing up, but it was a subterranean current in our lives. Meryl was the first person I texted when my mom collapsed, and after she died, I remembered that I hadn’t asked about Meryl’s father, Clayton, a handsome, broad-shouldered man with a head of thick black hair. Clay died 12 years ago, wrote Meryl.

On March 15 at 7 p.m., 11 days after Mom’s funeral, Meryl and I had the Phone Call. Our first phone call, I’ll mention again, in 20 years. I was nervous enough to think of texting that I was sick, or tired, or sad—at least two of which were true. I called Meryl from under my covers, and she answered from under her covers, and we picked up where we’d left off. Neither of us finished our sentences, instead letting our thoughts dangle dementedly. “I just think…Here’s what I’d say about that…My strong feeling there is…” Our conversation would have been mind-numbingly inane to anyone else, but we understood each other. We’d grown up in the same place, we saw things the same way, we didn’t need to explain ourselves.

That Meryl and I were moving irrevocably toward the Meeting filled me with unease. We chose the weekend of April 25, when she was to arrive by train at Union Station early on a Friday evening. There were at least 15 texts about the time of this arrival—Meryl, I woke up thinking you should get the train that gets you in at 5 on Friday…Is it a GO train or a real train?—which was when I realized how old we’d become. Of course, I lost her at Union Station. Where are you?!?…I am here!!…Where is here?? Cue 15 more texts until I saw Meryl across the chaos of the station’s endless renovation. Her head leaned left like the first time I saw her. We laughed as we hugged and mostly stared at each other on the subway until we got to my house.

After a night in Toronto, our plan was to return to our childhood hometown. The next morning, we took the bus to Grimsby, about two hours away. The sun was high and bright but gave no heat. We walked past the giant pink magnolia tree, now severely pruned, and bought flowers to put on Meryl’s father’s grave, which was on the escarpment. We walked the path to the top, and just as we called out our houses—“there, there”—like we did when we were kids, two red-tailed hawks circled overhead, their tails turning golden in the sunshine. They cocked their heads to look at us, as if we were the unexpected ones. Meryl took the hawks as a sign, I wasn’t sure of what.

We made our way to Clay’s grave, where we put our flowers on the stone Vivian had designed; it would soon be hers as well. Meryl lingered under the struggling sun, and I stayed a little ways back until she was ready to leave.

Back in Toronto that evening, we had dinner at a midtown bistro, and finally got to the hard conversation, about the night when Meryl tried to kill herself. “I can’t believe Vivian is 91,” I said. I’d asked for seats at the bar because I thought it would be more intimate to be side by side, but I saw my mistake right away. To Meryl, with people on either side and a bartender hustling in front, the bar felt like a decision against intimacy. “I think of Vivian as more my own age,” I said. “Of course that’s not right, but you know what I mean.”

“I can’t wait to tell her you said that. She liked being one of us.”

I poked at my arugula salad. “I’m sorry I didn’t know Clay died, Meryl.”

I wiped the smudge of lipstick off my wine glass with my napkin and wondered not for the first time how people didn’t leave crumbs or smudges, a talent I couldn’t master. Meryl’s place and glass were both pristine, like her memory. Even when I thought I knew something, like the right direction to take in traffic (so, so rare) or the turn of a story from the past, I mostly kept it to myself. There were other ways to get at the truth. Also, I didn’t care about being right the way some people did, that was the simple fact.

“When I saw the hawks today, I kind of thought it was your mom and my dad, protecting us.”

“I love that,” I said, but really I was having a hard time concentrating. It hadn’t been a plan, exactly, to talk about that long-ago night, but after 24 hours of conversation, it had begun to seem pathologically evasive not to. Forty-five years had passed, enough time perhaps to finally broach the subject.

“So I guess there are a couple of things we haven’t talked about this weekend. Like that night?”

Meryl didn’t change the subject so much as make her way toward it, ahead of us in the distance. “Remember the time we climbed the mountain by the creek bed? We would have been 12 or so. I remember that.”

“I think so.” I saw the faintest sparkle of a creek as I dabbed my finger at a lingering crumb. “We don’t have to talk about that night.”

Talking about difficult things was not who we were, Meryl and me. Not talking was what bound us, even. How could I have forgotten that? I racked my brain for a new subject.

Meryl looked at me calmly. I was beginning to suspect that I was the panicker, not she. “No, I want to,” she said after a while. “I mean, I never have, but I want to now.”

We both paused then, and I thought about the part of the story I knew. It would have been a couple of years after the creek-bed climb. Meryl was 14, and she took enough pills to die. Vivian rushed her to the hospital, barely in time to save her life.

“Things weren’t great at home in that time, you’ll recall,” Meryl said finally. She looked me straight in the face and waited. “Yeah,” I said, although I didn’t really recall, or perhaps only faintly. We’d finally acknowledged the thing we’d never discussed. We’d said out loud that it had happened, and that was enough. That was plenty.

“You weren’t depressed or anything,” I said.

Meryl kept looking at me, until she seemed to make a decision to leave it there. “I often think if my mom hadn’t come to my room and asked me if I wanted pizza, I’d be dead now. I often wonder about that.” She looked down at her lap, then up again at me. “And your mother was very kind in that time. She tried to help me, after. She took me to see a priest and told me I could talk to her anytime.”

“I remember being mortified that she took you to a priest, of all things.” I rolled my eyes, which made me wobble slightly on my bar stool.

“I think maybe I’m more religious than you are now.” Meryl let me absorb this new idea of her before she continued her story. “Your mom taking me to a priest was an act of concern. There wasn’t therapy or anything remotely like that. It was a private, shameful event. Even now, it’s a shameful event. No one, not even you and me, Cathrin—we never talked about it.” It wasn’t exactly an accusation.

I skated over the fact that it had taken me almost five decades to mention that night and instead went back to what I knew: that Meryl had called me and told me she’d taken pills from the medicine cabinet. I thought she was trying to get high, our steady preoccupation once we became teenagers, and asked her if it felt good. She said it did, but also that she felt kind of funny. “Cool,” I’d said, and went back to watching Star Trek or whatever was on TV. But as we talked on our shaky bar stools, what happened after that call took on more shape.

“I’m pretty sure my mom told your mom, and that’s why Vivian went into your room.” My words seemed to ring out, although I was speaking quietly.

“No, that’s not how it happened,” Meryl said, and I might have left it there because she’d been right about everything else. “It was dinnertime. My mom thought I was hungry.” Meryl smoothed her napkin on her lap and spoke again without looking up. “How would your mom even have known?”

My heart was pounding. I was getting in the way of how Meryl remembered that night, but my words were too fast for me. “She knew because when I hung up the phone, I told her,” I said, and I knew that it was true. Even though, at 15, I’d made hiding things from Mom a defining purpose of my teenage life, I must have understood that Meryl’s life, and in a way mine too, depended on my telling Mom, because what might life have been if my best friend had died that night—on my watch? Not great, was my guess. Now, sitting side by side with Meryl, I wasn’t only sure that my memory of that night was accurate, I cared that it was.

“If that’s true, then it was your mother who saved my life,” Meryl said. She looked directly at me. “If that’s true, then it was you who saved my life.”

“Well, you called me, so I guess you saved your own life.”

We both took time to settle after that. I became so lost in my thoughts that when I looked at Meryl again, I was surprised to see her still sitting beside me. She looked like she’d wandered a long way too.

“It wasn’t a condition, you know,” she said. “It was an episode. That’s how I think of it.”

“Yes, I get that.”

“I don’t talk about it because I don’t want to be defined by it. I’m not defined by it.”

“I think that’s true,” I said. “It was an incident, not a lifelong affliction.” Incident, episode, that night, that time, before, after—we were careful with our words. The other words felt too violent, and further from the truth.

“I’m proud of myself, how I rallied,” Meryl said. It was a statement, for both of us. “It took longer than people realized.” All weekend I’d been carrying around the idea that I needed to take care of Meryl, and in that moment, I let it go. She didn’t need looking after by anyone.

Back at my house, we put on our mothers’ pyjamas, as we’d agreed we would. We were both wearing our mothers’ clothes a lot at this point. I wore Mom’s red and black silk muumuu with its massive flapping arms. This muumuu had been her sister Mary’s, and Mom never washed it because it smelled of Mary and now I didn’t wash it because it smelled of Mom. That’s 30 years of smell on one muumuu. Meryl came out of my spare bedroom in her mother’s leopard-print silk pyjamas.

“Very Vivian,” I said.

“Very Vivian,” she said. Meryl liked to repeat my words; it was her empathy.

The next day, she left Toronto with a simple, factual question she could take to her mother about the sequence of events that night. They hadn’t talked about it either, so it wasn’t a small thing when Meryl sat with Vivian and asked her, “Mom, did you come to my room that night because Mrs. Bradbury had called you?” And my mom locked eyes with me, her eyes wide and so much pain in them, and she didn’t have the words, but she nodded yes. Meryl wrote this to me right away. To have this talk finally when she could no longer talk. It was strange, Cathrin. It was sad. It was huge.

I read the note from Meryl in my kitchen and started to cry, my tears plopping onto the round white table. It sounds dramatic to say that, because getting the details right about that long-past night was simple enough. Mom, Vivian and I would have done anything to save Meryl, so it didn’t matter who told whom. But knowing that it was all four of us, and that Vivian and Meryl had been able finally to nod that truth to each other? And knowing for sure that I hadn’t gone back to my Star Trek show. Beside the ordinariness was this hugeness, like Meryl said.

Six weeks after Meryl’s visit, Vivian died, and it was remarkable how that midtown bistro conversation happened when it did, exactly between the deaths of our mothers. It changed things for Meryl and me after that—if only we could have told our moms. Meryl would have asked Vivian to forgive her and told her how glad she was to have lived that night. And I’d have told Mom that I finally understood she had been my ally in important and even life-saving ways. My idea of her changed, but not only that, a new idea of myself began to take hold, a more reliable, less rickety one, like the Tea Room on the escarpment. I noticed something begin to grow in myself. A voice, maybe.

Excerpted from The Bright Side, by Cathrin Bradbury. Copyright © 2021, Cathrin Bradbury. Published by Viking Canada, an imprint of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Surprising Science Behind Friendship" width="295" height="295" />

Surprising Science Behind Friendship" width="295" height="295" />