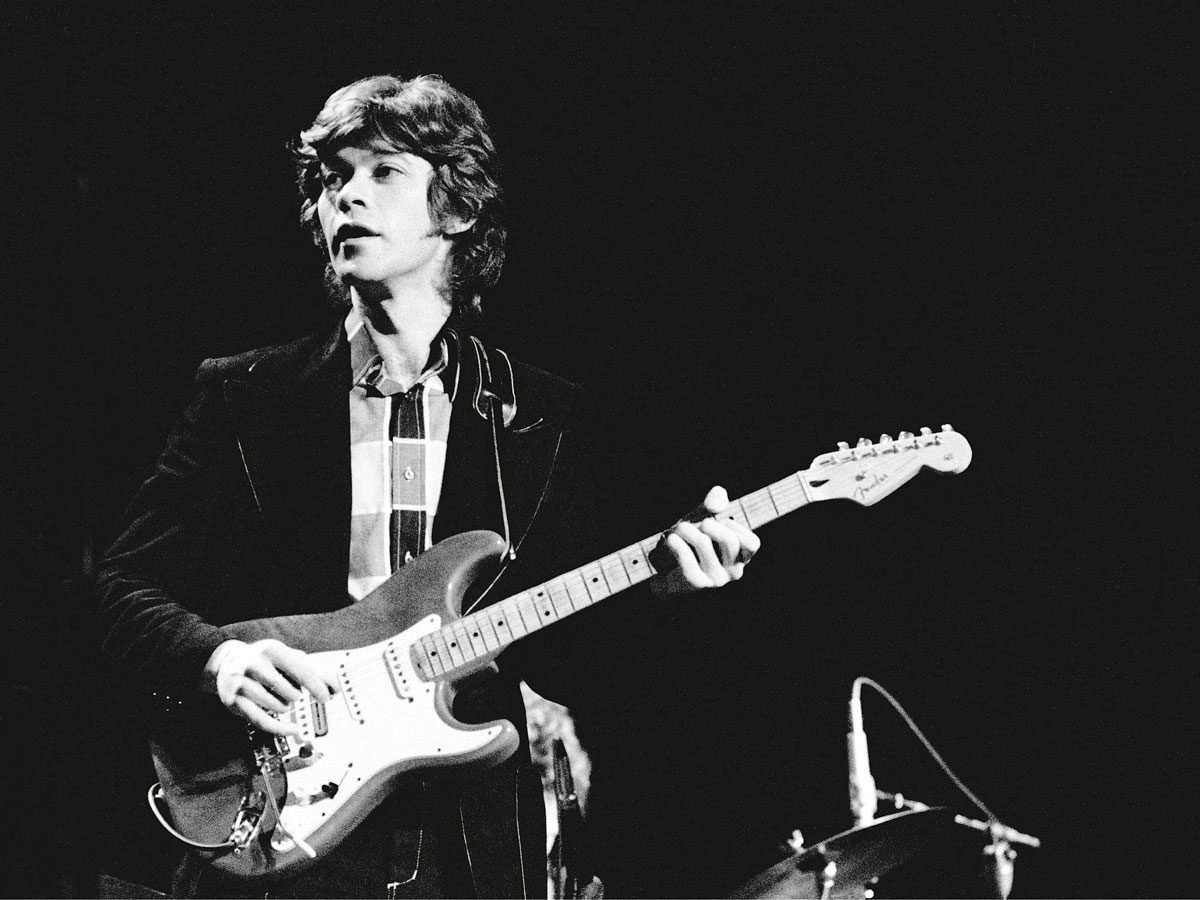

Legendary Songwriter Robbie Robertson Revisits His Freewheeling Career

Robbie Robertson penned some of the most memorable songs in rock. More than four decades later, he reflects on his wild days with the Band.

Mr. Legendary

When Robbie Robertson was a kid growing up in Toronto, his mother, who was born and raised on the Six Nations reserve near Brantford, Ont., often took him back home to visit her family. For Robbie, each trip was like a voyage to another dimension. His relatives had a profound understanding of the natural world and, most important to him, a great love of music. Everyone played an instrument or danced or sang, and Six Nations jam sessions, often held around a roaring campfire, were like small festivals of sound, light and colour.

Something even more transporting—and transformative—happened when he was nine. After lunch one day, Robbie joined a gathering at a longhouse. An elder sat in a large wood chair, draped in animal pelts, and recounted, with vivid imagery and riveting suspense, the tale of the Great Peacemaker who founded the Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy. Robbie was mesmerized. He told his mother that one day, he was going to tell stories like that.

It didn’t take long. Robertson began telling stories—or writing songs, same thing—when he was a teenager, then kept on telling them. There were the gentle puppy-love melodies he wrote for the rockabilly supernova Ronnie Hawkins, then the hits that he later wrote for himself. Robertson’s life story is something else, the story of rock music itself, its ups and downs, its evolutions and revolutions, its undeniable ascent and arguable decline. He is a one-man zeitgeist, a player, both major and minor, in some of popular music’s most defining moments.

He’s still best known, of course, for the groundbreaking songs he created with the Band, the wildly influential roots rock group—songs like “The Weight” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” The Band was renowned for its industry-defying lack of a front man. Eventually, and enthusiastically, Robertson took on that central role, to the enduring ire of his bandmates. And while his career with the Band lasted only a decade—1968 to 1978—his position as the group’s self-appointed chronicler has lasted about four times as long. Unlike the elder he first encountered as a child, however, the myth he’s recounting now is all his own.

I met Robertson in 2019, the day after a new documentary about him and the group, Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band, premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. He was tanned and tall and relaxed, his eyes hidden behind signature tinted glasses. Age diminishes us all, even Robbie Robertson, but he’s still ridiculously handsome. In conversation, he is as courteous as a courtesan or as winkingly elusive as his long-time comrade Bob Dylan.

Robertson was born Jaime Royal Robertson; Robbie was a neighbourhood nickname, derived, not so originally, from his last name. His mother, Dolly, was Mohawk and Cayuga, and his biological father, a Jewish man who was killed in a hit and run before Robertson was born, was a professional gambler. He was raised from birth by Dolly and his stepfather, Jim Robertson, a factory worker and war vet. Robertson’s home life wasn’t easy—his parents drank and fought, a lot. Jim would beat up Dolly, then turn his violent attention to his son.

After his relatives at Six Nations introduced him to music, he devoted himself to the guitar, and by 13 he had formed his first band, Robbie Robertson and the Rhythm Chords. Rock and roll had arrived: the radio was alive with Chuck Berry, Elvis, Buddy Holly and Little Richard. Robertson, who describes the discovery of rock as his “personal big bang,” was completely in its thrall. Everything changed: the way he dressed and talked and moved, the way he combed his hair, the way he strummed his Fender. Like it was for millions of teenagers, rock was an escape hatch that could propel him into an unknown future.

For Robertson, rock also looked like it could be a job, one where he could make some money and have a lot of fun doing it. At the time, Toronto seemed like a good place to start. Everyone from future Guess Who guitarist Domenic Troiano to Little Stevie Wonder and the Supremes partied at the city’s raucous clubs.

When Robertson was 15, his band the Suedes was invited to open for Ronnie and the Hawks. It was a revelation. Ronnie Hawkins had Kirk Douglas looks and James Brown moves. He was renowned for his acrobatic stage antics. Robertson had never seen anything like the Hawk, and Hawkins was likewise impressed by Robertson. He told his drummer, Levon Helm, “He’s got so much talent it makes me sick.”

When a spot for a bass player opened up in the Hawks, Robertson dropped out of high school, quickly taught himself the bass, and took a bus down to Arkansas, where Hawkins was currently living, to audition. He knew he was just a kid from Toronto. He worked as hard as he could, which was 10 times harder than everybody else. He learned the set list inside out—the bass and the guitar parts. He rarely slept, and when he did, he slept with his instruments.

“What I was trying to do was impossible,” Robertson told me, still somewhat awed by his own audacity. “I’m 16 years old. I’m too young to play in any of the places they play. I’m too inexperienced to play lead guitar in this group. And there’s no such thing in a Southern rock and roll band as a Canadian. With all these odds, it was impossible. And it was my job to overcome the impossibility. And win.”

He got the job. He won.

Levon Helm quickly became Robertson’s best buddy in the band, the big brother he never had. A few years older, Helm was, in some ways, Robertson’s opposite—short, Southern, hotheaded, with a devilish grin and white-gold hair. As other Hawks left, the rest of the band—Rick Danko, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson—suddenly became Canadian. They were a wild, impossibly talented bunch, and Hawkins worked them hard. They played six days a week and practised all night.

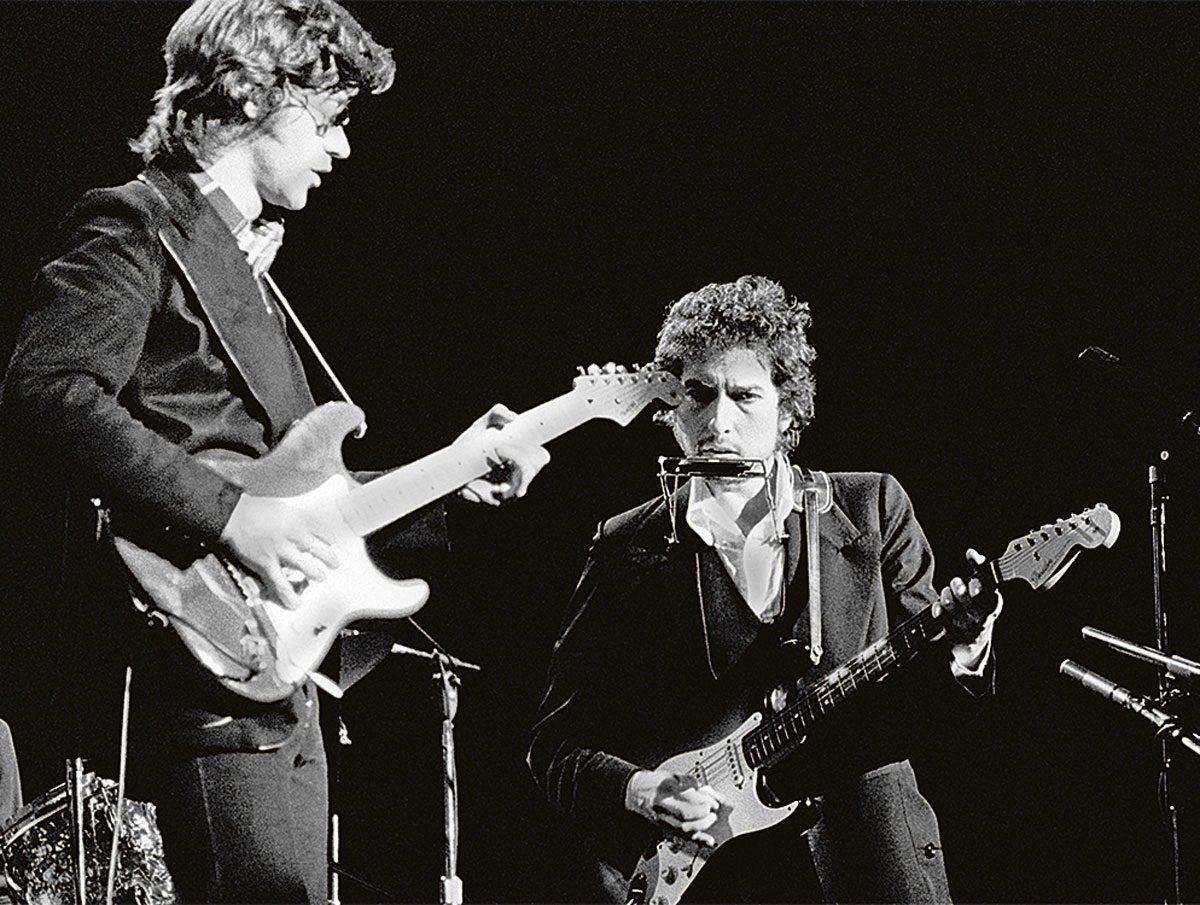

Hawkins, they soon realized, was holding them back. They craved independence, wanted to try new things. By 1964, they had split from Hawkins and abandoned the matching suits he made them wear. Soon after, they met a titanic musical force: Bob Dylan. Dylan had notoriously gone electric in 1965 and was looking for a band that could back him. It was the big time, but it was also an unexpected, dispiriting gauntlet. Betrayed folk audiences dismissed Dylan as a fame-hungry sellout. They booed his shows. Many blamed the Hawks, claiming they were ruining Dylan’s music.

By that point, Robertson was 22 and living in New York. Dylan had opened up his world. Robertson got a suite at the Chelsea Hotel. He was meeting everybody: Allen Ginsberg, Salvador Dalí, Carly Simon. On a movie set, he palled around with Marlon Brando, who kindly opened a Coke bottle for him with his teeth. At Dylan’s first wedding, he served as best man. A world tour took him off the continent for the first time, and he travelled to Hawaii, Europe, Australia.

Dylan, however, was exhausted. A motorcycle accident in 1966 gave him the opportunity to, as he said, “get out of the rat race.” He retreated with his young family to Woodstock, in upstate New York. The Hawks followed, with Danko, Hudson and Manuel settling in a ranch house they dubbed Big Pink. Robertson and his future wife moved into their own place up the road, and Helm, who had temporarily left the Hawks, rejoined the gang. They transformed the Big Pink basement into a recording studio.

The basement became one of the most legendary laboratories in the history of rock. Here, the group created the quasi-field recordings and oddball ditties that became known as The Basement Tapes. Here, they composed their first record, 1968’s Music From Big Pink, including one of the most indelible songs in the American pop canon, “The Weight.” They then defiantly renamed themselves the Band, mainly because that’s what everyone in Woodstock called them.

If Robertson’s discovery of rock and roll had been a big bang, now, at long last, he had formed his own galaxy.

A year later, the Band cut their self-titled sophomore record, and it too contained instant classics, including “Up on Cripple Creek” and “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” The songs sounded like hymns written in the backroom of a 19th-century saloon, boogie-woogie ballads. They were woven from each of the group’s different singers, and no voice seemed more central than another. This was part of the Band’s secret, Helm said.

It would also be its undoing. Despite their ostensibly democratic configuration, the story of the Band soon became, as it did for so many musical acts, the story of who was the true voice of the group. Robertson and Helm vied to be the soul of the Band—or at least to be recognized as such. As the Band became more and more successful, the question of who was responsible for that success became an issue.

Robertson had written fewer than half the songs on Big Pink—Manuel was the other principal songwriter—but by the Band’s third album, Stage Fright, he was writing all of them. Initially, the Band had shared the publishing royalties equally, but by their sixth studio album, 1975’s Northern Lights–Southern Cross, Robertson had bought out Manuel, Danko and Hudson’s ends. He had written these songs, so why shouldn’t he get paid for them?

At least this is how Robertson tells it. In 1993, Helm published his own memoir, This Wheel’s on Fire, a rollicking, occasionally vitriolic tell-all that praises Robertson in one paragraph and excoriates him in the next. “The old spirit of one for all and all for one was out the window,” Helm wrote. “Resentment just continued to build.”

That resentment spilled over when Robertson proposed, in 1976, after seven studio albums, that the Band stop touring, regroup and figure out what to do next. He was tired of the road, which he’d never liked much to begin with. Plus, he was plotting his next move, which he hoped would be the movies: producing them, writing music for them, starring in them.

He befriended Martin Scorsese, a man who loved music as much as Robertson loved movies. They agreed that Scorsese would film the Band’s last concert, to be held at the Winterland Ballroom in San Francisco, where they’d played their first show. “The Last Waltz,” as Robertson referred to the show, was electric, transcendent and joyous, and the ensuing movie is among the best concert films ever released. Afterward, Robertson refused to tour with the Band again and would never again make a record with them.

Robertson knows he’s been vilified. But he’s a guy more inclined to self-mythologizing than self-reflection. I asked him how it felt to be known as the guy who had put the Band together but who had also torn it apart. “I was the one who wanted the Band to continue,” he said. “I was the one who was the driving force in this group, and I drove it and I drove it until there was nothing to drive anymore.”

He didn’t care if I believed him, or what other people said. They weren’t there. And they aren’t here now. Except for the reclusive Hudson, Robertson is the only original member still alive. He was the one who’d survived, he was the one who got the last word, and here he was getting it again with me. He insists that he made peace with Helm before he died in 2012. “I thought to myself, what all he and I did together and all the things we came through and the music we made and this life experience, nothing can compete with that.”

It must be strange to be an elder, though, at this point in rock’s history, when so many of your musical brothers are no longer with you and others are blinking in the twilight. It must be strange when, like Robertson, you talk and talk about the past, and the stories from the past keep informing the story of the present. Robertson didn’t see it that way. “My natural mode is moving on, moving on, moving on,” he said. “What I’m doing with my life has to do with today and tomorrow. So these things, it feels good to go there because I don’t go there very often.” That wasn’t quite true. It was another story. But I sat and listened.

Next, here are the best concerts you can watch online right now.

© 2019, Jason McBride. From “Robbie Robertson’s Last Waltz,” Toronto Life (November, 2019), torontolife.com