Cari MacLean’s Brush With Death

Ron MacLean was out on the ice when the firefighters entered the arena. It was a Tuesday evening in October, and the Hockey Night in Canada host was wrapping up an adult hockey league game. The moment he spotted the firefighters, Ron’s mind flashed to teammates who’d had health problems in the past. Oh, God, he thought as he skated toward the bench, Rob or Bill had another cardiac. That’s when he noticed players pointing in his direction. The firefighters—who had just answered a 9-1-1 call at Ron’s home—told him that his wife, Cari MacLean, had been taken by ambulance to the Oakville-Trafalgar Memorial Hospital. She had instructed them to find him. “It’s okay, you have time to get dressed. But you should get there immediately,” they said.

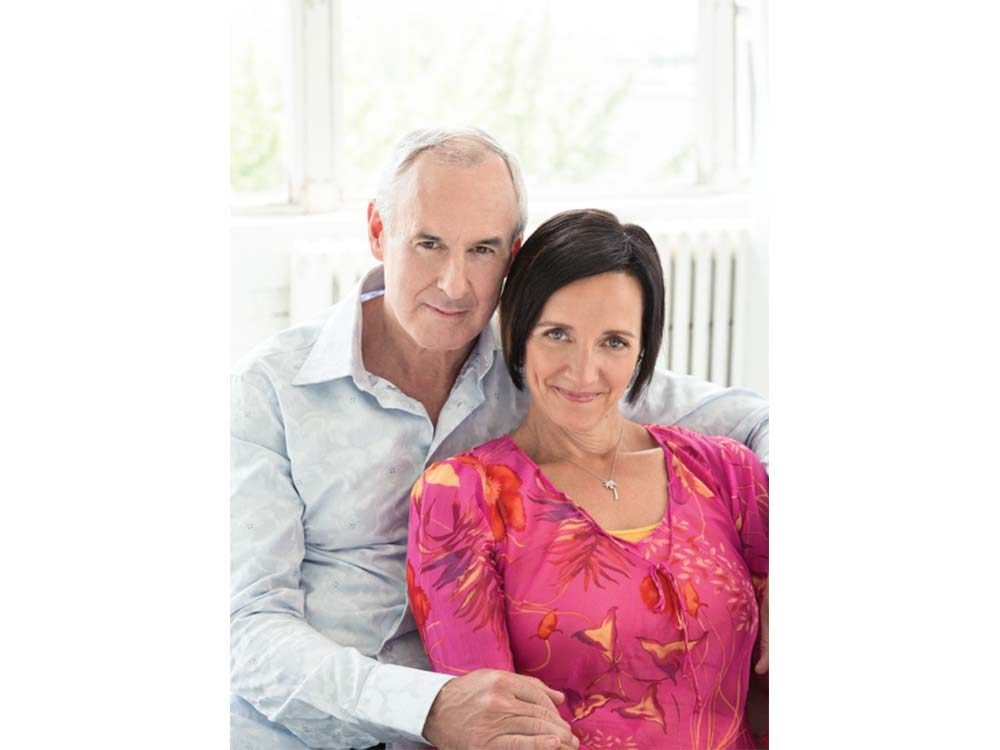

Ron wheeled out of the arena lot, nearly smashing into a car backing out of its spot. He knew Cari hadn’t been feeling well, and he was trying to stay calm. The couple live in Oakville, an affluent suburb west of Toronto. They both spent their teenage years in Red Deer, Alberta, and have been together since 1978, when Ron, in Grade 12, became smitten with the Grade 10 point guard who, he later realized, looked like Jennifer Beals from Flashdance. He began seeking Cari out at school and at parties, and he timed his trips to a local ice cream shop so he’d run into her on her way home from basketball practice. Eventually, he won her over. When Cari went to university in Edmonton and Ron started his broadcast career in Red Deer, he’d gun down the highway to see her on weekends.

He had rushed to Oakville-Trafalgar once before. In 1990, just before the first game of the Leafs-Blues playoff series, his three-month-pregnant wife called him in St. Louis to say she was having serious abdominal pain. Ron jumped on a plane but got stuck overnight in Pittsburgh. When he finally arrived, Cari had lost the child. The couple was devastated. They tried again, and then again, but at a certain point it became clear they weren’t meant to be parents. For 28 years, they’d had only each other. Now he feared the worst.

Cari MacLean isn’t used to lagging behind. She plays hockey and runs marathons. When she couldn’t keep up with her running group last fall, she chalked it up to age and lack of conditioning. She’d turned 50 and had spent a leisurely summer neglecting to train. Perhaps she had a cold. Any of these things could explain the shortness of breath, the unfamiliar weakness.

On Thanksgiving Monday, Cari felt a cramp in her calf—the same sensation she’d had the previous April, after a flight to Vietnam. Tuesday evening, with the cramp no better, she texted a friend to say she was going to skip hockey. After Ron left to play in his own game, she went upstairs and ran a bath to try to loosen her calf. That’s when, overcome by nausea, she started vomiting. She managed to pull herself out of the tub and looked in the mirror. She was shocked: her face, drenched in sweat, was white as soap.

From her ensuite bathroom, Cari looked over at her bed, a few feet away. She couldn’t imagine summoning the strength to make it that far. She gathered some towels and made a makeshift bed on the floor. She lay down and curled into the fetal position. Then she heard a voice. “No,” it said. “Get up, get dressed, call 9-1-1.” She felt hypnotized. Everything in her body wanted to lie down, but the voice kept insisting, “Get up, get up, get up.”

Although the MacLean’s had a land line, all Cari could picture was her cellphone down in the kitchen. She pulled on what clothing she could and crawled on all fours, taking the stairs step by agonizing step. When she finally reached the phone and called 9-1-1, the operator asked if the patient was still breathing. “I’m the patient,” Cari answered weakly. “I’m in trouble.”

Learn how Ron and Cari MacLean’s story saved this reader’s life.

An Uncertain Situation

Mangesh Inamdar was in the middle of his eight-hour shift when the nurses called him to the ER. A youthful 42-year-old, Inamdar possesses the love of adrenalin that marks so many emergency physicians. When he graduated from medical school, his plan was to become a radiologist, someone who pored over X-rays and MRIs in a quiet room. During his residency, however, he found himself drifting over to the intensive care unit, moonlighting there despite a full workload. Maybe it was the variety of cases he got to work on or the satisfaction of seeing swift results or the immediacy of life-or-death situations, but he kept coming back.

When the paramedics wheeled in Cari MacLean, Inamdar knew something was dangerously wrong. Her face was drained of colour, and her pulse was almost non-existent. Most worrying was her blood pressure. For a woman her age, it should have been 120 systolic. Cari’s was 60—frighteningly low. (Here are nine surprising factors that could affecting blood pressure readings.) The blood pressure suggested a few possibilities: ruptured aorta, internal bleeding, fluid around the heart, septic shock or a major heart attack. (Learn to spot the silent signs of a heart attack here.) The possibility that Inamdar kept coming back to, however, was a massive pulmonary embolism.

A pulmonary embolism occurs when a blood clot, generally in the calf, works its way up the circulation system and blocks the blood vessels in the lung. It isn’t pretty, and death comes quickly. Many never make it to the ER—they die at home or in the ambulance. In fact, in his 14 years as an emergency physician, Inamdar had never seen anyone survive.

But as Inamdar continued to investigate, he began to have doubts. Because a pulmonary embolism starts as a clot in the leg, usually a patient will have a swollen calf. Cari’s calves, however, were perfectly symmetrical. Another telltale sign is troubled breathing, but Cari told him she didn’t feel any pain in her lungs. She had felt shortness of breath, but she’d also had sniffles and had been vomiting—symptoms that pointed toward a virus.

Inamdar was confused. A CT scan could reveal the truth, but Cari was so unstable that he couldn’t risk bringing her out of the ER. Low oxygen levels were another sign of massive pulmonary embolism. The most accurate reading is done with a small oxygen monitor attached to a patient’s fingertip, but Cari was wearing gel nails that were impossible to remove without soaking them in acetone for 15 minutes. Because she had no perceptible pulse, they couldn’t draw blood from her wrist to test for oxygen, so Inamdar went with Plan C: attaching an oxygen monitor to her earlobe.

The results were astonishing. While oxygen levels for someone as physically fit as Cari could exceed 99 per cent, the earlobe monitor was telling Inamdar that Cari was at just 30 per cent. The result was basically incompatible with life.

Don’t miss this incredible story of a boy who came back to life after being dead for two hours.

Saving Cari MacLean

Inamdar didn’t know what to think. Cari had been there 10 minutes and was conscious as the nurses rushed around her, adjusting her IVs and checking her vitals. The reading was so low it could have been an error—earlobe monitors are notoriously unreliable for gauging oxygen levels. But if it wasn’t an error, then Cari would suffer respiratory arrest at any moment.

“I remember thinking, I don’t have a diagnosis and this lady is going to die,” Inamdar says. “I think all of the nurses in that room felt the same thing. Because we’ve all seen the look of death.”

When Ron MacLean arrived in the ER, Cari was surrounded by medical staff. His wife appeared weak and seemed to have countless needles in both arms connected to the IV lines. When she leaned over to vomit in a bedpan, the needles came out and Ron could only watch helplessly as the nurses reinserted them. But despite all this, Ron was oddly heartened. Cari looked pale, yes, but she wasn’t showing obvious signs of trauma. Standing in his jeans and baseball cap, among the beeping machines and the bustling nurses, he felt a sense of calm. “It seemed to me that everything we needed was right there,” he says. When Inamdar fired off questions, he answered as quickly and accurately as possible. It was like doing a live hockey broadcast, he thought. Do your part and then get out of the way to let the experts do their jobs. Every once in a while, he would reach out and touch his wife’s arm. “You’re doing great,” he told her. “Things are going great.”

Then things started to get worse. Cari had now been in the hospital 20 minutes and began to shake wildly. Inamdar knew that 70 per cent of patients who die from pulmonary embolisms die within the first hour. If that was what she was fighting, he needed to act.

The treatment for a pulmonary embolism is a thrombolytic—a drug that dissolves blood clots and would, with a bit of luck, clear the pathway to the lungs. But if Cari didn’t have a pulmonary embolism and was actually suffering from some sort of internal bleeding, she would bleed out, and Inamdar and the nurses would be helpless to stop it. If his hunch was right, the thrombolytic could save her. If he was wrong, it would kill her.

Inamdar conducted an ultrasound, desperately searching for new information. Cari didn’t have any blood in her belly, which ruled out internal bleeding. He looked more closely at her heart. Cari’s right ventricle seemed to be larger than her left ventricle, a sign of pulmonary embolism. It was the nudge he needed. “We’re giving her the thrombolytic,” he said.

While the nurses rushed to prepare, he hustled to the computer. Treating pulmonary embolism is rare enough that the protocol is still somewhat experimental. So while Cari lay dying on the bed, Inamdar took the unusual step of typing “thrombolytic, massive pulmonary embolism” into Google. He scanned some medical studies and came up with a plan: rather than give her the medication in small doses, as some studies suggested, he would give it to her all at once. The small-doses method meant administering the medication over a period of two hours. “I did not have two hours,” says Inamdar. Once he started the treatment, there was no turning back.

Ron didn’t know what a pulmonary embolism was and had no idea what it did to a healthy body. But as Inamdar gave the order, Ron realized the situation was far graver than he had imagined. He watched Inamdar bring his nurses together. “It was almost like a huddle when the game is tied and the teams are about to head into overtime,” Ron says. “He said, ‘Sheila, what is your drug, what is your dosage and what order are you administering in?’ Then he did it to the next nurse, and then the next.”

The nurses gave Cari the drugs through her IVs. She’d now been in the ER for 40 minutes, and everyone waited, watching her bedside monitor. Ron didn’t know what to look for, so he and Cari locked gazes. Both understood that this might be the last time they would stare into each other’s eyes. The machines beeped, and Cari’s vital signs flashed in waves across the screen. Finally one of the nurses smiled. “This is good,” the nurse said, encouraging her. Cari’s blood pressure was moving up. Her oxygen levels were rising. She was coming back.

Later that evening, when Cari was stable and Inamdar was certain she’d escaped the worst, she finally got her CT scan. It showed a big clot in her artery and many smaller clots in her lungs. It was enough to piece together a theory about what had happened. Inamdar explained that blood had clotted inside a vein in her calf during her flight to Vietnam in April (because of altitude, dehydration and cramped conditions, up to five per cent of air travellers end up with clots). It broke off and slowly worked its way into her lungs, causing her fatigue and breathing troubles. As Ron and Cari studied the scan, Inamdar didn’t need to say what all of them now knew: she had been minutes away from death.

For the next few months, Cari slowly came to terms with the enormity of what had happened to her. As she recovered, a certain anxiety remained. She found herself reluctant to return to running. The idea of feeling that way again—constricted chest, lungs aching for breath—was too frightening, and so she put it aside.

But finally, with much encouragement from Ron, she laced up her shoes again. (Here’s what happens to your body when you start a new running workout.) It was spring, after a winter that seemed like it would never end, and the crabapple trees were in bloom. As Cari jogged through her Oakville neighbourhood, past the tidy lawns and old brick houses she’d seen for years, everything suddenly looked new.

“The clichés about near-death experiences are true,” she says. “I look at things differently now. I feel like I’ve become very small and big at the same time. Small in the sense that this is what life’s all about—right now, right at this moment. But at the same time, I have this appreciation for how much bigger everything is. Our lives are just specks, just temporary. You hear that all the time, but I have a better appreciation of that.”

The couple still talk about that evening in October—going back and forth over the details. Cari likes retelling how she overheard the cardiologist on the morning shift looking at her chart. “He did what?” he said, incredulous, when he learned about Inamdar’s decision.

Ron prefers to describe the moment Inamdar made the gutsy call: “His arms were folded and his feet were at 9-o’clock and noon. It was a stance of desperate resignation. He knew he was taking a risk, but felt he had no options. He was the first star of the night.”

Next, find out 30 ways to boost your heart health.

Warning Signs of Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

Each year, more than 20,000 Canadians are hospitalized for pulmonary embolism (PE), a blockage of a lung artery caused by a blood clot that has travelled from another part of the body, usually the legs. The larger the clot, the greater the danger, with roughly 10 per cent of cases ending in death. Risk of PE increases if you have cancer, are overweight, are pregnant, take birth control pills or have recently had surgery.

Small PE

- Symptoms: Unexplained calf swelling, laboured or pained breathing (caused by dead lung tissue), coughed-up blood.

- Action: Go to an ER. If caught in time, a small PE can be treated with blood thinners.

Large PE

- Symptoms: Sudden light-headedness, shortness of breath, weakness, loss of colour, intense perspiration.

- Action: Call 9-1-1. Any delay may prove fatal.

Safe Flying

- Long-haul flights (four hours or more) can trigger the formation of blood clots, known as deep-vein thrombosis, the condition that precedes a pulmonary embolism. Here are more ways long flights affect your body.

- While on the plane, a few minutes of low-intensity activity every two hours will boost circulation.

- Consider a quick walk up and down the aisle, or a simple flex-and-point exercise with your toes.

- A single 81-milligram dosage of Aspirin a half-hour before boarding can help thin the blood.

- Stay hydrated. Drink fluids regularly during your flight and go easy on the booze.

- Watch your calves in the months following the trip. Any swelling could be the telltale sign of a clot.

Here are more things smart travellers always do before a flight.