“It was a prisoner’s life.”

One August morning in the south Lebanese town of Zefta, nine Syrian children sit in a sunlit classroom. Display boards around them are pasted with cheerful icons—drawings of a balloon, an ice cream cone, a smiling doctor with a stethoscope. The class of boys and girls, in jeans, long skirts and t-shirts, is attentive. There is no chatter.

The teacher reads words in English for the class to repeat. Takwa, an 11-year-old girl in the first row, leans forward and follows along in her workbook. “Door, window, table, chair,” she says. She savours each day in the school and each newly acquired word because, before these classes, she hadn’t set foot in a school for nearly four years.

It was back in November 2014, in the Syrian farming village of Ghanem Ali, that Takwa’s education was cut short. She was at her local primary school when a group of bearded, black-clad strangers burst through the doors. The children cowered in fear while the ISIS fanatics ripped pictures from the walls and set fire to the Syrian flag. As smoke wafted down the hallways, the terrified children ran home to their parents in tears.

In dozens of classrooms across the river valley similar shocking scenes unfolded. ISIS closed schools, forbade education but opened them later with a new brainwashing to replace the standard curriculum. They also imposed harsh new dress codes and banned locals from smoking, drinking or leaving their village. “It was a prisoner’s life,” says Takwa’s mother, Rahma Jasem Al Mousa.

That’s how Takwa became one of the more than 2.8 million Syrian children deprived of regular schooling in the months and years after war began in 2011. The conflict has left a whole generation at risk of illiteracy, without the opportunity to learn skills to rebuild their lives or country. More than five million Syrians have fled, and the vast majority took refuge in neighbouring countries that are themselves struggling with poverty. So, the life that many Syrians arrived to was one of hardship—where education was either unavailable or took a back seat to the struggle to survive.

From helping families affected by physical disabilities to giving sexual abuse victims a voice, these Canadians are making an impact within their own communities.

“Welcome to the hive.”

This was the case for Takwa and her family, who in July 2017 finally escaped Syria and made the perilous journey to Lebanon. They found an apartment in Zefta, a town 60 kilometres south of Beirut. Lebanon was relatively stable. However, jobs for Syrian refugees were almost entirely restricted to construction, cleaning and agriculture, and Takwa’s father could only find only irregular, casual work.

“The large majority of refugees are in poverty,” says Bill Van Esveld, senior researcher for children’s rights at global humanitarian NGO Human Rights Watch, “Kids are expected to go out and work to support the family and girls are subject to increased pressure to marry early.”

Although schools across Lebanon had devised a system to let refugee children attend, splitting the school day into two “shifts”—one in the morning for Lebanese and another in the afternoon for Syrians—in practice it wasn’t available to all. The head teacher at the family’s local school welcomed Takwa’s younger siblings, who’d never been in school before, but said Takwa, then 10, and her brother Rashid, then nine, would have to start again at the bottom. Syrian schools teach only in Arabic, whereas Lebanese schools teach some subjects in English or French—and there was no language support available for the older children.

But those children living near Zefta were fortunate. In June 2017, a school for refugee children opened its doors in the village. Housed in a modest apartment building, the school doors open at 8:30 a.m. when children stream into four classrooms from a school minibus. Coloured drawings of giant bees plaster the walls and a sign reads: “Welcome to the hive.”

In one classroom, children aged three and four sit around low tables passing crayons to one another, colouring in red shapes. A tape plays in the background of a woman singing. “It’s to calm them,” explains Sarah as Younes, she gives a tour of the centre. Sarah leads psychosocial support sessions that make up an hour of each child’s day. When some refugees start school, they cry or can’t sit still, she says. In Sarah’s classes they’re encouraged to express their feelings. Difficult stories come out. But she lets each child talk, and—when they have finished—gently moves the subject on. “It’s so as not to let them feel sad all the time. They have to learn to start from the beginning, in a new atmosphere,” she says.

After about three months tuition at the school in literacy and numeracy, split into manageable two six week “cycles,” most children would be ready to enroll in Lebanon’s public schools.

It all began far away in Italy, back in 1972, when a group of young friends founded the Association of Volunteers in International Service (AVSI). Over the decades, AVSI expanded and education became a key part of its work. In the wake of the Syrian crisis, it and other NGOs collaborated to found a network of community schools. AVSI took responsibility for four in Lebanon, among them the school in Zefta.

The network of schools aims to help the more than 27,000 refugee children across Lebanon and Jordan over three years. But although the school is warm and safe, has dedicated teachers and a minibus to bring the children to the school, it has had its work cut out. When it first opened, many Syrian kids living nearby had been out of the classroom for years. AVSI knew that they’d need outreach workers to coax children in. Alaa Baassiri, a 30-year-old from the nearby town of Saida, is one of a team of four outreach workers, hired to take on the challenge in January 2017. It has been surprisingly difficult.

Find out why greeting Syrian refugees with parkas is the ultimate Canadian act.

“A lot of my friends’ parents were not educated because of the civil war…”

Alaa’s first mission to a village called Kfarmelki was tough. With his colleagues, he began knocking on doors, eager to recruit some pupils. But as soon as parents realized why he was visiting, the atmosphere soured. “Go away,” said one man. “I don’t want to meet NGOs. They’re all liars.”

By the end of the first day, 10 kids were registered, bringing them an important step closer to the classroom— but the parents of eight others still refused to discuss it. Their trust would have to be won. But Alaa and his team kept going back to Kfarmelki. Over three months of visits, their success rate increased and they were adding as many as 25 kids in one day to their register. Finally, the last of the families from the very first day also invited Alaa’s team to sign them up. They’d seen the other kids coming back from classes, happy and energized. “Neighbours have a big influence,” says Alaa, grinning.

This success was an early boost. But as his work went on, Alaa came up against new kinds of problems, he explains as he embarks on a day of outreach visits. At one door, a gaunt man invites him into the modest family apartment over a supermarket. Abdel Hamidi, 40, a stone-carver from Idlib, shows off framed examples of his intricate handiwork—but explains that despite his skills, he can’t find enough work and can barely afford food.

Abdel reveals that his younger son Mohammad, seven, is enrolled in a government school—but his two eldest, Hsein, 13, and Sami, 12, are not. They’re both working for five dollars a day, Hsein in the shop downstairs and Sami for a water delivery service. Abdel’s wife Marwa bursts into tears. “Any parent would want to send their child to school,” she says. But their financial situation is stopping them. The answer’s no, for now.

Alaa—the son of a doctor who grew up in the nearby city of Sidon—admits that this work can be emotionally tough. He is afraid that if children aren’t helped into school, Syria faces “an uneducated generation” and he knows only too well what that means. “A lot of my friends’ parents were not educated because of the civil war,” he says, referring to Lebanon’s sectarian conflict of 1975 to 1990. That war disrupted education across the country, leading to poverty, high infant death rates and further violence.

Thanks partly to Alaa’s work, the classrooms at the school in Zefta have begun to fill. In the first nine months of 2018, 460 children took classes here. Outside is a walled courtyard where the kids play games. But this is also where, at the end of each six-week cycle, the teachers hold a mock-graduation ceremony. They can’t hand out certificates, a power reserved for government-run schools, so they have crafted a cardboard frame with a mortarboard stuck to the corner. The kids take turns to be photographed smiling in the centre, their toothy grins recorded to seal the hopeful moment.

Back in the school, in an Arabic class Maan, aged five, rises to his feet and sings the first tentative notes of a song. Teacher Laura Hijazi’s heart swells, because during Maan’s four weeks at the centre he has been unable to join in with class singing. He and his mother fled ISIS under heavy shelling in May last year. But Laura, 30, paid him special attention, giving him stars, toys or balloons as symbolic rewards whenever he got something right. Now, he relaxes into seven lines of Arabic lyrics, finishing with the words: “I come to my school and see my teacher and all my friends here beside me.” As his song ends, his classmates give him a round of applause.

Don’t miss these powerful true stories of Canadian veterans.

“Education is light, and ignorance is darkness.”

Seven weeks after she began school, Takwa sits behind her desk in Arabic class. Her teacher hands out plastic blocks marked with words in Arabic. They must match their first block, which says “the letter R”, with other words starting with R. It’s learning by playing, explains teacher Riman Ezzeddine. “We must help them feel safe. And confident,” she says. She turns to Takwa, who first gives the word in Arabic for pomegranate, raman. Then she gives the name of her brother Rashid who is in the classroom, too. Riman gives Takwa a gold star.

She sometimes encourages Takwa to teach her brother at home—a mark of her trust in a particularly diligent student. But it’s also a way of helping the girl to picture a future more prosperous than her past, because Takwa has revealed that she has a dream. She hopes to become an Arabic teacher.

Across the country, the situation for refugee children is still “terrible”, says Bill Van Esveld of Human Rights Watch. He points out that government and NGO targets for enrolment overall are unambitious, given that in 2017 more than 300,000 of 630,000 Syrian children living in Lebanon were still not in formal schooling. Greater government action is needed, he says, “or we will continue to fail these children.”

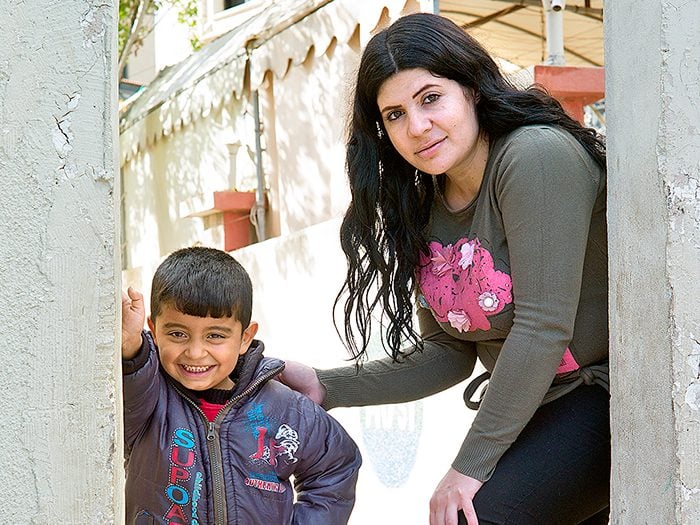

Like refugees across the country, this family still faces challenges. Takwa’s mother Rahma is eight months pregnant and suffers from anaemia. She is homesick for Syria, and worried her youngest boy is malnourished. For now, though, says Rahma, the school in Zefta brings bright spots of pride and joy—valuable for refugees worn down by uncertainty.

“The children are so excited to go and learn,” she says. Her own schooling is rudimentary—she struggles to read and write — but she’s come to prize learning all the more. “Education is light, and ignorance is darkness,” she says.

We’ve rounded up the most inspirational stories from across the globe.