Stephen Leacock’s Most Unforgettable Character

In 1876, when I was six years old, my father settled on an Ontario farm. There, we lived in an isolation the like of which is almost unknown today. We were 50 kilometres from a railway. There were no newspapers. Nobody came and went, for there was nowhere to come and go.

Into this isolation broke my dynamic uncle, Edward Philip Leacock, my father’s younger brother. E.P., as everyone called him, had just come from a year’s travel around the Mediterranean. He was about 25, bronzed and self-confident, with a square beard like a Plantagenet king. His talk was of Algiers, of the Golden Horn and the Egyptian pyramids. To us, who had been living in the wilderness for two years, it sounded like The Arabian Nights. When we asked, “Uncle Edward, do you know the Prince of Wales?” he answered, “Quite intimately”—with no further explanation. It was an impressive trick he had.

In that year, 1878, there was a general election in Canada, and E.P. was soon in it up to the neck. He picked up the history and politics of Upper Canada in a day, and in a week, he knew everybody in the countryside. In politics, E.P. was on the conservative, aristocratic side, but he was also hail-fellow-well-met with the humblest. A democrat can’t condescend because he’s down already, but when a conservative stoops, he conquers. E.P. spoke at every meeting. His strong point, however, was socializing in barrooms, which gave full scope to his marvellous talent for flattering and make-believe.

“Why, let me see,” he would say to some modest rural resident in threadbare clothes beside him, glass in hand, “surely, if your name is Framley, you must be a relation of my dear old friend General Sir Charles Framley of the Horse Artillery?”

“Mebbe,” the flattered fellow would answer, “I ain’t kept track very good of my folks in the old country.”

“Dear me! I must tell Sir Charles that I’ve seen you. He’ll be so pleased.”

Thus, in a fortnight, E.P. had bestowed distinctions on half the township of Georgina. They lived in a recaptured atmosphere of generals, admirals and earls. How could they vote any other way but conservative!

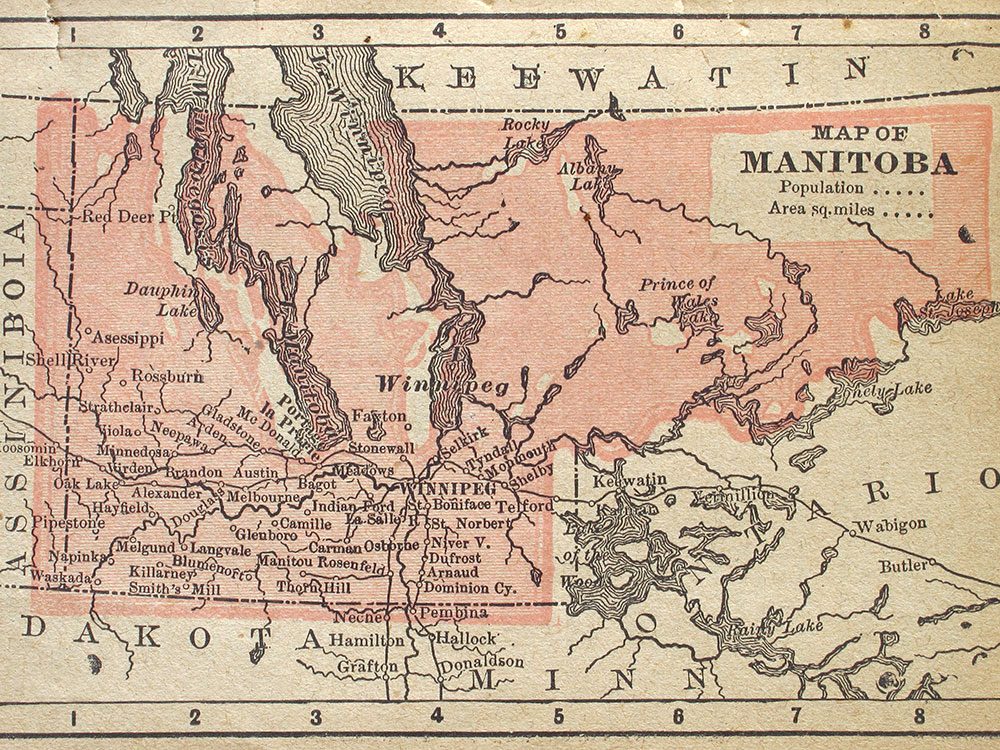

The election was a walkover for John A. Macdonald. E.P. might have stayed to reap the fruits, but Ontario was too small a horizon for him. Manitoba was then just opening up, and nothing would satisfy E.P. but that he and my father should go west. So we had a sale of our farm, with refreshments for all comers, our lean cattle and broken machines fetching less than the price of the whisky. Off to Manitoba went E.P. and my father, leaving us children behind at school.

They hit Winnipeg on the rise of the boom, and E.P. rode the crest of the wave. There is a magic appeal in the rush and movement of a boom town—a Carson City of the 1860s, a Winnipeg of the 1880s. Life is all in the present, all here and now, no past and no outside—just a clatter of hammers and saws, rounds of drinks and rolls of money. Every man seems a remarkable fellow; individuality shines, and character blossoms like a rose.

Check out 20 Extraordinary Facts About Reader’s Digest Canada!

The Manitoba Boom and Bust

E.P. was in everything and knew everybody, conferring titles and honours up and down Portage Avenue. In six months he had a great fortune, on paper. He took a trip east and brought back a charming wife from Toronto. He built a large house beside the Red River, filled it with pictures of people he said were his ancestors and carried on a roaring hospitality inside it. (Every Canadian should visit these Toronto attractions.)

He was president of a bank (that never opened); head of a brewery (for brewing the Red River); and secretary-treasurer of the Winnipeg, Hudson Bay & Arctic Ocean Railway. They had no track, but E.P. received free passes for travel over all of North America.

He was elected to the Manitoba legislature; they would have made him prime minister but for the existence of the grand old man of the province, John Norquay. At that, in a short time, Norquay ate out of E.P.’s hand.

To aristocracy, E.P. added a touch of prestige by always being apparently about to be called away—imperially. If someone said, “Will you be in Winnipeg all winter, Mr. Leacock?” he answered, “It will depend a good deal on what happens in West Africa.” Just that; West Africa beat them.

Then the Manitoba boom crashed in 1882. Simple people like my father were wiped out in a day. Not so E.P. Doubtless he was left utterly bankrupt, but it made no difference. He used credit instead of cash; he still had his imaginary bank and his railway to the Arctic Ocean. Anyone who called about a bill was told that E.P.’s movements were uncertain and would depend a good deal on what happened in Johannesburg. That held them another six months.

I used to see him when he made his periodic trips east—on passes—to impress his creditors in the west. He floated on hotel credit, loans and unpaid bills. A banker was his natural victim. E.P.’s method was simple. As he entered the banker’s private office he would exclaim, “I say! Do you fish? Surely that’s a greenheart casting rod on the wall?” (E.P. knew the names of everything.) In a few minutes the banker, flushed and pleased, was exhibiting the rod and showing trout flies. When E.P. went out, he carried $100 with him. There was no security.

He dealt similarly with credit at livery stables and shops. He bought with lavish generosity, never asking a price. He never suggested payment except as an afterthought, just as he was going out. “By the way, please let me have the bill promptly. I may be going away.” Then in an aside to me he’d say, “Sir Henry Loch has cabled again from West Africa.” And so on. They had never seen him before and wouldn’t again.

When ready to leave a hotel, E.P. would call for his bill at the desk and break out into enthusiasm at the reasonableness of it. “Compare that,” he would say in his aside to me, “with the Hôtel de Crillon in Paris! Remind me to mention to Sir John how admirably we’ve been treated; he’s coming here next week.” Sir John was our prime minister. The hotelkeeper hadn’t known Canada’s elected leader was coming—and he wasn’t.

Then came the final touch. “Now let me see … $76 …” Here, E.P. fixed his eye firmly on the hotel man. “You give me $24, then I can remember to send an even hundred.” The man’s hand trembled, but he gave it.

This does not mean that E.P. was dishonest. To him, his bills were merely “deferred,” like the British debt to the United States. He never made, never even contemplated, a crooked deal in his life. All his grand schemes were as open as sunlight, and as empty.

Check out this list of Canada’s most fascinating exports!

An Evening in the Sunset

E.P. knew how to fashion his talk to his audience. I once introduced him to a group of my college friends, to whom academic degrees meant a great deal. Casually, E.P. turned to me and said, “Oh, by the way, you’ll be glad to know that I’ve just received my honorary degree from the Vatican—at last!” The “at last” was a knockout. A degree from the Pope, and overdue at that!

Of course, it could not be sustained. Gradually faith weakens, credit crumbles, creditors grow hard and friends turn away. Little by little, E.P. sank down. Now a widower, he was a shuffling, halfshabby figure who would have been pathetic except for his indomitable self-belief. Times grew hard for him and, at length, even the simple credit of the barrooms broke under him. My brother Jim told me of E.P. being put out of a Winnipeg pub by an angry bartender. E.P. had brought in four men, spread the fingers of one hand and said, “Mr. Leacock. Five.” The bartender broke into oaths.

E.P. hooked a friend by the arm. “Come away,” he said. “I’m afraid the poor fellow’s crazy, but I hate to report him.”

Free travel came to an end. The railways found out at last that there wasn’t any Arctic Ocean Railway. E.P. managed to come east just once more. I met him in Toronto—a trifle bedraggled but wearing a plug hat with a crepe band around it. “Poor Sir John,” he said, “I felt I simply must come down for his funeral.” Then I remembered that the prime minister was dead and realized that kindly sentiment had meant free transportation.

That was the last I ever saw of E.P. Finally, someone paid his fare back to England. He received from some family trust an income of two pounds a week, and on that he lived, with such dignity as might be, in a remote village in Worcestershire. He told the people of the village—so I learned later—that his stay was uncertain: it would depend a good deal on what happened in China. But nothing happened in China.

There he stayed for years, and there he might have finished but for a strange chance, a sort of poetic justice, that gave him an evening in the sunset.

In the part of England whence our family hailed there was an ancient religious brotherhood with a centuries-old monastery and dilapidated estates. E.P. descended on them, since the brothers seemed an easy mark. In the course of his pious retreat he took a look into the brothers’ finances and his quick intelligence discovered an old claim against the government, large in amount and valid beyond doubt. In no time E.P. was at Westminster, representing the brothers. British officials were easier to handle than Ontario hotelkeepers.

The brothers got a lot of money. In gratitude they invited E.P. to be their permanent manager. So there he was, lifted into ease and affluence. The years went easily by among gardens, orchards and fish ponds as old as the Crusades.

When I was lecturing in London in 1921 he wrote to me. “Do come down; I am too old now to travel, but I will send a chauffeur with a car and two lay brothers to bring you here.” Just like E.P., I thought, the “lay brothers” touch. But I couldn’t go. He ended his days at the monastery, no cable calling him to West Africa.

If there is a paradise, I am sure the unbeatable quality of his spirit will get him in. He will say at the gate, “Peter? Surely you must be a relation of Lord Peter of Titchfield?” But if he fails, then may the earth lie light upon him.

Looking for more stories from the Vault? Check out Jesse Owens’ greatest triumph!