This Man Was Stung a Thousand Times by Killer Bees—And Survived

The only way to save his friend from the killer bees was to climb up the mountain and back into the swarm.

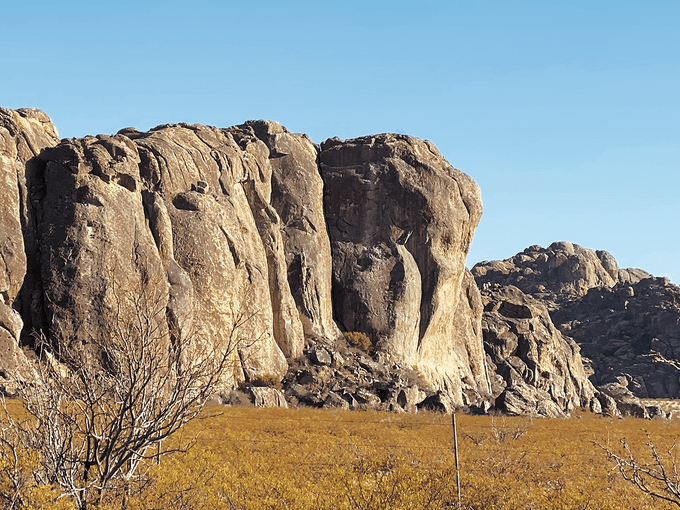

The rock hills of Hueco Tanks rise dramatically above the scrubby Chihuahuan Desert in West Texas—four masses of weathered syenite that have long been a rock-climbing paradise.

In May 2015, Doug April was finishing a six-month stint as a camp host at Hueco Tanks State Park, living by himself in an RV. The lanky 46-year-old was divorced with three kids, the youngest in junior high. He had served two tours of duty in Iraq, where he saw plenty of things that were hard to forget. Throughout it all, climbing had been a refuge. Out on the rock, he could turn off his buzzing mind and just concentrate on what was in front of him.

Now that respite was coming to an end. April had officially left the army three weeks earlier, retiring as a major, but he wasn’t through with war zones. In a few weeks, he was headed to Afghanistan for three months to fly reconnaissance missions as a private military contractor. He wanted to make the most of his last days of climbing.

Around 8:00 a.m., April’s climbing partner, Ian Cappelle, pulled up to the campsite. The 38-year-old geologist had moved to El Paso with his wife, Malynda, five years earlier. Shortly after, while out climbing, he’d met April. They’d been buddies ever since.

Burly and bearded, Cappelle didn’t necessarily look the part of a climber. But as soon as he’d tried the sport, he was hooked. He regarded April as a kind of big brother—an experienced climber and generous teacher.

“What should we do today?” April asked as they packed their ropes that morning.

“Well, you’ve been up Indecent Exposure twice already,” Cappelle said. “I’d like to do that route.”

April paused. Indecent Exposure had always given him the heebie-jeebies. It wasn’t the most difficult route in Hueco Tanks, but it was probably the most intimidating. It had two “pitches,” or sections, and both had passages that left you hanging out over big 75-metre drops, unprotected. Midway along the route there was a plaque in memory of a University of Texas at El Paso student who had died while attempting it.

But when it’s one of your last climbs for a long time, you want to make it a memorable one.

The day was beautiful. The sun was just right, the breeze perfect. If Cappelle agreed to lead the first part of the climb, April said he would lead the second.

Cappelle climbed out to his right, his chalked fingers finding their way to the cliff’s handholds. He and April were tethered together for safety, with two lines of rope connecting them through belaying devices on each of their harnesses that would act as a brake, holding the rope tight if either of them fell.

As Cappelle led the way, he clipped the rope into metal anchors drilled into the rock face for protection. Twenty minutes into the climb, he saw the memorial plaque and silently paid his respects. He made it to the ledge that marked the end of the pitch and attached himself to an anchor. April followed and they paused for a moment to rest, 40 metres up in the air.

April led the second pitch. The hardest section came early on—a huge step to the right, followed by a few metres of slim, fingertip-and-toe edges. He’d had trouble there in past attempts, but this time he nailed it, making his way to a flake of rock about the size of a refrigerator.

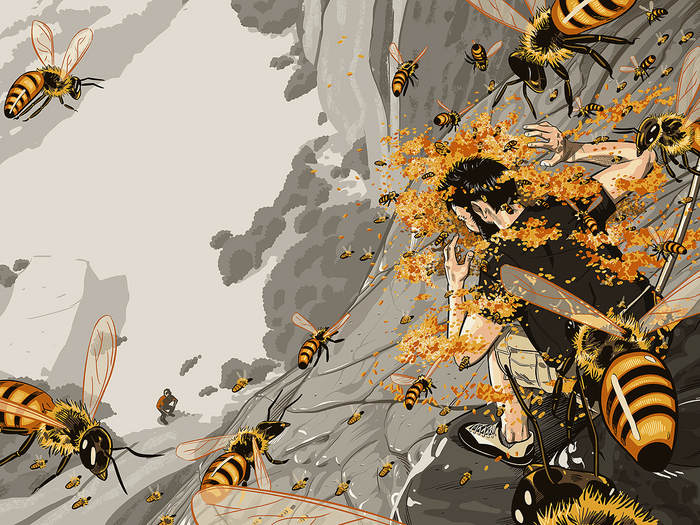

“Oh man, that was great!” he called out across the chasm, a few metres above his partner and eight metres out to the right. Then: “This is weird. Where did all these bugs come from?” April slapped the back of his neck. He looked down and, in the next moment, watched in terror as a cloud of bees swirled out of the rock—more bees than he’d ever seen, like a scene from a horror movie. The swarm enveloped him in an instant, stinging him over and over again, the pain spreading across his neck and face and body.

Regular honeybees can sometimes be territorial, but Africanized bees are much more aggressive. They arrived in this hemisphere in 1956, when African bees introduced to Brazil to increase honey production escaped, bred with European honeybees and quickly spread across the Americas, making their way to the southwestern United States by the 1990s.

When Africanized bees sense a threat, they don’t just send a couple of bees to ward it off—they send hordes, chasing a person for up to 400 metres until the threat is eliminated. If someone’s stung 1,000 to 1,500 times, scientists estimate, they’ve got a fifty-fifty chance of dying. Since the 1950s, swarms of Africanized bees have been responsible for more than 1,000 deaths; there’s a reason they’re known as “killer bees.”

A moment after the bees swarmed, Cappelle watched in horror as April jumped off the ledge, feeling the jerk of tension in his harness as his partner’s weight pulled the rope taught. “Lower me, lower me, lower me, go, go, go!” April yelled.

From his perch, a slim ledge about a metre across and just half a metre deep, Cappelle played out all 60 metres of rope, ripping it through the belaying device as fast as he could. Below him, the wall undercut the ledge he was standing on, and April disappeared from view.

That’s when Cappelle saw the first bee flying toward him. He stood as still as he could, figuring if he just ignored it, it should go away. Instead, it flew straight at him and stung him on the neck. The stings came quickly after that—one, two, three, four, and then a crescendo of pain as the bulk of the hive attacked him. Cappelle tried to cover his face, the high-pitched whine drowning out everything as the bees attacked his ears, eyes, nose and mouth.

His mind raced as the bees stung him. Why hadn’t Doug unclipped himself once he reached the ground? Once he unclipped, Cappelle could pull up the rope, anchor himself into the wall and rappel down to safety. But April was still hanging there, dead weight on the end of the rope.

Cappelle stood on the slim ledge and sucked water out of his climbing bottle, desperate to stay hydrated to stave off the effects of the venom. What do I do? What do I do? He reached up to brush the bees off his head and felt a halo of insect bodies an inch thick, stinging him over and over again. Call your wife, he thought. Tell her you love her. But what if he dropped the phone?

The toxins coursed through his bloodstream. At a certain point, the panicked thoughts subsided, replaced by a strange sense of calm. It was a terrible way to go. He was so sorry Malynda was going to lose him like this, but there was nothing he could do. The world shrunk around him, squeezing to a pinprick, and Cappelle blacked out, slumping down onto the rocky ledge.

Below him, April hung suspended in mid-air, two metres away from the wall and about 20 metres off the ground. He’d been stuck that way for about 10 minutes, and the bees hadn’t stopped stinging.

“Untie the blue rope!” he yelled up to Cappelle. He wanted Cappelle to use one of the ropes to rappel himself to the ground. But neither man could hear the other. All they could hear was the deafening buzz.

After so many stings, April’s body was becoming numb to the pain. He could feel the bees climbing all over him, but the stings hardly registered. One flew into his mouth—vibrating and fuzzy, with a slight flowery taste—and he quickly spat it out. After more than a dozen stings, people can experience vertigo, nausea and even convulsions and fainting. April had been stung hundreds of times. He pulled his ball cap over his face and tried to think.

He had always been able to keep his head in a bad situation. He’d crashed a helicopter in training and seen men die in combat. And no matter the danger, he’d always been able to flick a switch in his brain. Turn off the fear. Concentrate on what needs to be done.

What needed to be done now was clear: he had to climb down. The mountain was criss-crossed with climbing routes—he just had to find one. About five metres away, he spotted an anchor that was part of another route. He swung himself toward the bolt, caught it on the third try and clipped himself in. Then he released the ropes that were attached to Cappelle, leaving them dangling in the wind.

On a good day, this wouldn’t have been that difficult of a route, but this wasn’t a good day. He was pumped full of bee venom, his body inflamed and his mind swimming. He carefully picked out a route down.

The climb down took him about five minutes, but it felt like forever. By the time April made it to the ground, he was nauseous and nearly delirious. He stumbled toward the road, just as one of the park rangers pulled up.

“Ian,” April gasped, gesturing up at the cliff. He and the ranger called Cappelle’s name. They could see him up on the ledge. He was in the fetal position, a massive cloud of bees surrounding him. “Ian!” he yelled again. His friend didn’t move.

April did the math in his head. Someone had already called search and rescue, but it would take them about an hour to get a team from El Paso. And to get a team that could safely climb down to Cappelle and remove him? That could take climbers who didn’t know the area a few hours more. Cappelle likely didn’t have that much time.

April knew what he had to do. “Drive me back to my car,” he said to the ranger. “I’ve got another rope in there. I’ll go get him.”

April scrambled up the rocks as fast as he could. He’d decided to hike another route up the back of the mountain, then rappel down to Ian. He wore the park ranger’s radio, as well as a mesh net that he pulled over his ball cap.

Part way up the trail, he ran into two other climbing friends and conscripted them into the rescue plan. By the time they reached the top, it had been about 45 minutes since the start of the attack, and April had no idea if his friend was alive or dead. Even in his nauseous state, it didn’t cross his mind to ask one of his fellow climbers to head down instead. It was his partner down there—he would be the one to go and get him. April set an anchor at the edge of the cliff and clipped himself in. One of the other climbers began belaying him down.

For about the first 15 metres, Cappelle was out of sight. Finally, the cliff grew steep enough that he could see his partner, still motionless, covered by a swirling blanket of bees. “Ian!” he yelled. And this time Cappelle looked up.

“He had the same look I’ve seen too many times in combat, where someone’s been blown up or shot,” April remembers. It’s not fear, exactly—more a look of pure incredulity. How the hell did this happen to me? “That’s how he looked at me. Then he put his head back down.”

April made his way down to the ledge. The bees were all over him again, but by now he was entirely numb to them. He attached Ian to his belay device. “I’m going to get you out of here,” he said. Cappelle was just conscious enough to follow April’s simple instructions, while April carefully lowered him 40 metres down to the ground. Below them, the first ambulance was just pulling up.

April watched as the rangers and paramedics collected Cappelle. Then he lowered himself as quickly as he could. By the time he reached the ground, Cappelle was in a helicopter destined for the hospital in El Paso. It was only then that the search-and-rescue team arrived.

April turned down the paramedics’ advice to go to the hospital. Although he felt faint, he didn’t believe he was going to die anytime soon.

In the parking lot, he ran into two climbers who had wilderness first aid training. April stripped down to his boxers. The best way to remove the stingers, they told him, wasn’t to use tweezers, which squeezes the poison from the venom sacks into your body. The two men used their credit cards to scrape him down, sloughing off hundreds of stingers into the desert sand.

At the hospital, doctors estimated that Cappelle had been stung more than a thousand times—a high enough dose to be lethal. He had been lucky. And with a day or two to flush it out of his system, he would be fine.

Months later, after April returned from Afghanistan, the men planned a climb—back at Hueco Tanks.

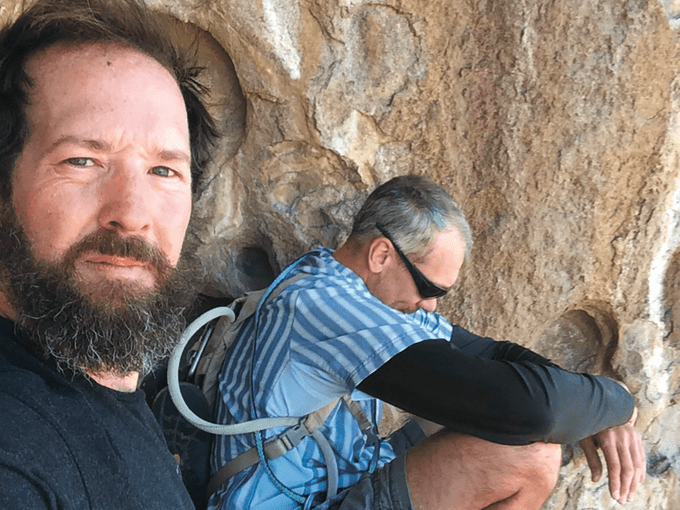

They took a different route this time, and any trepidation they might have felt being out there dissipated in the fresh air of another perfect day. They reached a little alcove high above the desert and sat down to rest.

In the months since the attack, Cappelle had had plenty of time to think about what could have happened if April hadn’t come back for him that day. His one memory after he blacked out is a flash of a thick carpet of dead bees covering the cliff ledge and then, entering the picture, April’s red shoes.

On the ledge, he tried to tell April how much he appreciated what he’d done, but his friend waved him off. It hadn’t even been a choice. “There was just no way he wasn’t going to try to help me,” says Cappelle.

The two men took in the view. Out there, in the Basin and Range Province, just a little elevation gives you sweeping vistas in every direction. The Franklin Mountains sat out to the west, hazy and indistinct. To the north, 140 kilometres away, you could see the faint outline of the Sacramento Mountains silhouetted against a sky that seemed endless. The sun was just right, the breeze light. They stood up again, the rope strong and secure between them, and went back out on the rock.

Next, read about how this rescuer refused to quit searching when a scuba diver got lost in a cave.