The Fascinating Origins of Butter Tarts—Canada’s Most Beloved Dessert

Where did the butter tart come from? And is it still a butter tart if you add bacon? Here’s the surprisingly controversial story of this sweet little treat.

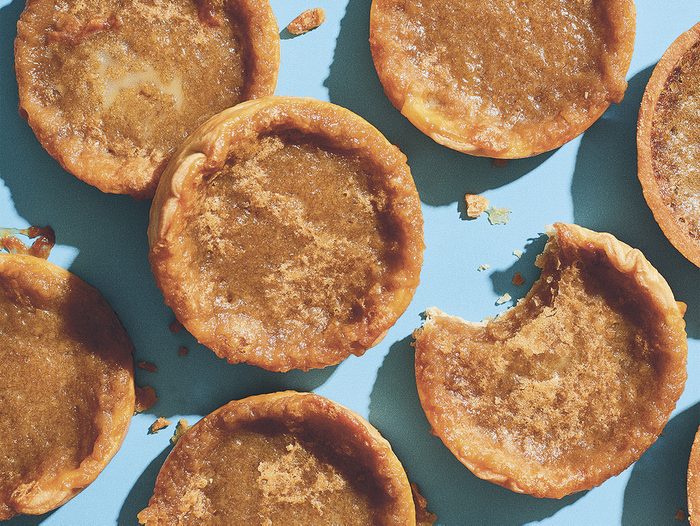

Within its fragile pastry shell and its sticky filling of butter, sugar, syrup and egg, the butter tart holds Canada’s memories of long weekends, country bakeries, recipes handed down through generations—and an eternal debate over raisins.

Though it is made from pantry staples, the alchemy of a butter tart’s ingredients makes for something all its own. And its simplicity means you’ll usually have what you need on hand to whip up a dozen. Plus, they freeze well (some say they taste even better frozen, especially on a hot summer day).

But why do butter tarts and Canada seem so inseparable?

For me, it’s the memory of eating oozing tarts on a cottage deck in the midday sun, followed by a dive into the lake to wash off all the sticky residue. Often, it was too hot to bake our own, so my family and I would drive into town and wait in line for butter tarts at the local café, sometimes sharing one on the car ride home.

Whatever your own experience, the butter tart is firmly tied to our Canadian identity. People become lifelong devotees to the tart, pledging undying loyalty to their local bakery or their mother’s version.

Here’s the surprisingly controversial story of this sweet little treat.

Controversy #1: The Butter Tarts Origin Story

The exact origin of butter tarts is unknown. Some credit the filles du roi: the young French women who settled in New France between 1663 and 1673 to marry voyageurs. They combined their knowledge of pastry with the ingredients on hand and, according to the Canadian Encyclopedia, created butter tarts.

Others look to settlers from the “border counties” between Scotland and England, who arrived in Canada in the 1800s toting Ecclefechan tarts, also called border tarts. Food writer Elizabeth Baird believes the treat, filled with dried fruit and made in a pie tin, evolved into the butter tart. Further proof? Immigrants from the same region also settled in Georgia, home to pecan pie.

However, culinary historian Liz Driver, author of Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825–1949, suggests that perhaps homemakers who had dairy, eggs, flour, lard and brown sugar put them together into a humble tart to feed farmhands, family and visitors year-round. This, she says, explains the butter tart’s similarities to Quebec’s sugar pie (which contains whipping cream); the butter tart is a parallel invention born of necessity and similar circumstances. “Why is it,” she asks, “that Canadians can’t just accept that we made something ourselves?”

Controversy #2: National Dessert Status

Does the butter tart deserve icon status in our broad and diverse country? If nostalgia and history are reason enough, then the answer is yes. In 2019, Canada Post even put the butter tart on a limited-edition stamp. (It did not, sadly, taste like a butter tart.)

If that’s not enough, then also consider age and geographic supremacy: butter tarts date to at least the early 1900s and are popular from Newfoundland to British Columbia. But what about Nanaimo bars, a latecomer to the handheld dessert scene, having originated in the 1950s? Well, a 2018 voting bracket created by Daybreak North, a CBC radio show in B.C., still crowned butter tarts the champion holiday treat over Nanaimo bars.

Okay, so they’re nationally revered, but are they a Canadian icon? South of the border, Americans have largely remained unaware of our beloved tart—their loss. In classic Canuck fashion, many Canadians find it more reason to propel the tart to icon status.

Controversy #3: Tours, Trails and Tension

Across the country, tens of thousands of Canadians have taken part in festivals and tours that celebrate the not-so-humble butter tart. It seems every small bakery, especially in rural Ontario, sells them—some displaying ribbons and awards from taste-offs and festivals. The largest festival is Ontario’s Best Butter Tart Festival, which has been running since 2013 in Midland. (In its inaugural year, the festival sold out of 10,000 tarts by 11 a.m.) Around 65,000 people come for one butter tart-filled day in June every year.

In 2006, bakeries and businesses in Wellington County, Ontario, launched Canada’s first self-guided butter tart tourist trail. In 2011, the Kawarthas Northumberland tourism board started a butter tart tour of more than 50 stops through the Kawartha Lakes district, Northumberland County, and Peterborough, Ontario. The Wellington trail team was not pleased and sent a cease-and-desist letter to the new tour. Things calmed down after the two sides met over butter tarts (yes, really) and decided to co-exist.

Controversy #4: The Perfect Butter Tart

Raisins or no raisins? Our passion over the addition of dried fruit has become an ongoing conversation among Canadians. Perhaps it’s what keeps our country together: we love to bicker over something so small and so sweet.

Nuts vs. no nuts: While some (including me) feel that walnuts or pecans take the tart into pie territory, others prefer a little crunch.

Other add-ins: Formerly restricted to raisins, currants and nuts, fillings have started to reflect our country’s diverse cuisines. For creative bakers the tarts are a canvas to experiment with flavours such as cardamom, Nutella, ginger and miso. Some tarts definitely push the classic recipe—there are versions filled with cheesecake or that taste like poutine. Bacon is becoming a popular add-in and bolsters the case for eating butter tarts at breakfast.

Runny or firm? Do you like them so gooey that you’ll need a swim after, or firm enough to eat one-handed while doing chores? Until you find your favourite, maybe you’ll just have to keep testing them all.

© 2020, Emma Waverman. From “The Surprisingly Controversial Story of the Butter Tart,” Cottage Life. (July 6, 2020).

Now that you know the butter tarts origin story, check out 10 must-try Canadian dishes (and the best places in the country to find them).