Drama in Real Life: Trapped in a Fiery Wreck

Even now, Beatrice Roberts can’t recall why her truck veered off the highway and burst into flames. But she knows who she has to thank for saving her life. A Reader's Digest Canada classic, originally published in 2014.

The world was spinning. Seconds earlier, Beatrice Roberts had been driving her red Ford F-150 down a stretch of stick-straight highway she’d taken for years. Sunlight glimmered in her rear-view mirror as she headed home to Grand Falls-Windsor, a 14,000-person town in central Newfoundland. Inexplicably and in an instant, she’d crossed the yellow line of that familiar two-lane road, and her truck was crashing toward the side of the highway. As the steep ditch zoomed closer, Roberts braced herself. She watched the rocky ridge smash into her windshield, shattering the glass.

A retired store clerk and cook, the 63-year-old had lived in Grand Falls for 20 years. As she was driving, Roberts had thought about her mother, whom she had just visited in Springdale, an hour and 20 minutes away. Last fall, her mother had had a stroke, and she’d lived with Roberts and her husband, Terry, throughout the winter. But by May, the family had decided a long-term-care facility was best, and a weekly ritual had begun. Roberts would spend time with her mother outside, chatting with other residents or watching TV. That Sunday, July 27, 2014, should have been just like the others. Instead, Roberts was screaming for her life by the side of the road.

“The truck is on fire!”

Ryan Folkes could feel the sun on his face as he drove his black Ford F-150 truck along the Trans-Canada Highway. It was a stretch of road he’d been down hundreds of times, just outside his hometown of Grand Falls-Windsor. Here, thick copses of black spruce and balsam fir line the paved two-lane highway, which is so flat you’d think you were in the Prairies. Based in Gagetown, N.B., Folkes was on a week-long vacation from his post as a corporal in the armoured corps of the Canadian Armed Forces. It was good to be home. He hadn’t visited in about a year, and he’d come to appreciate the place more than he had before his nine-month stint in Afghanistan in 2012. Four of his military friends—Ryan Elliott, Nick Bronson, Adrien Guindon (a former soldier) and Lee Westelaken—plus Elliott’s wife, Danielle, had come along for the trip, eager to see the Rock for the first time. It was a vacation six months in the making. They’d spent an idyllic first few days kicking back at Folkes’s family cabin, which the 26-year-old had helped build, half an hour outside of town.

That afternoon, Folkes had planned to take the group to Leech Brook, a trio of waterfalls where locals loved to hang out. The boys had piled into the pickup, Billy Currington’s country song “Pretty Good at Drinkin’ Beer” blaring over the speakers. In his rear-view mirror, Folkes could see Westelaken and the Elliotts following behind in their car. The six would spend the day at Leech and later head into town to Folkes’s parents’ place for dinner—steaks on the barbecue, probably, Folkes thought as he passed a stretch of green.

“The truck is on fire! The truck is on fire!” Rodney Mercer cried out to curious passersby climbing out of their cars to survey the scene. He and his wife, Jennifer, a gynecologist with the Central Newfoundland Regional Health Centre in Grand Falls-Windsor, had skidded to a stop after seeing a red truck roll over a steep embankment on the side of the highway. Normally, their 21-month-old triplets would be in their back seat, but they’d taken Rodney’s parents up on an offer to babysit. Perpetually exhausted, the couple figured they’d make the most of the hazy day and take their new boat out to Badger Lake, about half an hour away.

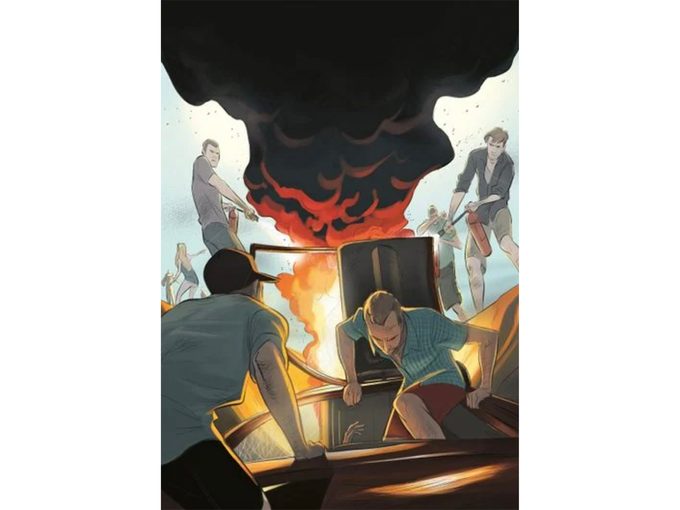

The Mercers vaulted into the ditch, where the truck had landed on the passenger side. Clouds of smoke emanated from the engine, and Jennifer urged the other drivers to stay back. Rodney, a Grand Falls town councillor and teacher, ran for the extinguisher he knew was buried in the back of the boat behind their car. Sprinting back, he was followed by two men who attempted to dampen the flames that were now shooting skyward with dirt and gravel. A woman in one of the first vehicles behind them to stop yelled out that she was calling 9-1-1.

“Help me!” Roberts screamed over and over from inside the truck. Struggling to breathe, she could smell the smoke. “We’re here,” Jennifer called back. “We’ll try.” Roberts could see the orange glow in the truck’s hood moving closer to where she was pinned, her right foot lodged behind the pedals and her body draped over the inflated airbag. She’d released her seat belt after the crash, a gut reaction that left her deeper in the truck-and harder to reach. The three men were keeping the fire at bay, but just barely. Each time they thought they had put it out, the engine would shoot out more flames. They knew they couldn’t win.

Moments later, the five soldiers ran up. They had pulled over to the roadside when they spotted the smoke trailing into the sky, and they immediately sprang into action. They had each been trained in emergency extraction from vehicles and advanced first aid, and, having served together in the same squadron for nearly six years, quickly fell into a rhythm. Folkes and Westelaken hopped on top of the truck, wrenching the door open with their hands. The smaller of the two, Westelaken climbed inside the cab, taking Roberts’s hand. Folkes hovered above, assessing the damage, before following Westelaken. “Check on the fire,” he told Elliott, who had firefighting experience.

“You gotta hurry up…”

Meanwhile, bolstered by instinct and adrenalin, the growing crowd of over a dozen passersby morphed into a series of moving parts. Danielle directed traffic on the two-lane highway and shooed away rubberneckers snapping photos with their smartphones. Another civilian ripped up a yield sign from the side of the highway and carried it to the truck to use as a makeshift stretcher. The soldiers scrambled to get to Roberts before the fire did, racing against the sparks still flying out from under the buckled hood.

“I need to know how long we’ve got,” Folkes asked Elliott. He looked back at Folkes. Not wanting to alarm Roberts, the 25-year-old responded quietly. “You gotta hurry up,” he said, looking his friend in the eyes. Bystanders handed Elliott fire extinguisher after fire extinguisher, but it wasn’t enough. Until the local fire department arrived on the scene, there was only so much to be done.

Folkes climbed down into the cab’s back seat, and together he and Westelaken managed to shove the front seats back to give Roberts more space. Her left foot was dangling, nearly severed. She had cuts up and down her legs, so deep on the left side the men could see pockets of fat below the skin. “What’s your name?” Folkes asked her, determined to keep her from panicking. He was accustomed to first aid in combat; he’d never seen anything like this so close to home. “Where are you from?” She answered clearly, alert through her tears. The friends worked quickly, and in minutes they’d extracted Roberts and lifted her carefully out through the door, passing her to Guindon and two men waiting at the top of the truck, before climbing out after her. The men laid Roberts gingerly on the yield sign; the soldiers each took a corner, while the civilians followed behind, keeping her legs from swinging. A grim procession, the group carried Roberts carefully to the other side of the road, about 40 metres from the truck.

“Get back!”

At the same moment, Elliott, realizing the blaze had progressed beyond an exhaust fire and was going to blow, yelled at bystanders to get back. Three minutes later, the truck exploded, caving in on itself and sending up a wall of flames that separated Elliott, on the highway’s south side, from the rest of the group to the north. Suddenly alone, the young soldier turned and glanced down the highway. Stopped cars stretched out in both directions beyond the horizon.

With Roberts safely on the highway shoulder, the soldiers and Jennifer, along with two nurses also on the scene, began to treat her injuries as best they could. One bystander hauled over a 12-pack of Pepsi to use as an improvised splint for her injured legs, while another grabbed blankets from surrounding cars to keep her warm. Others pulled first-aid kits from their glove compartments, handing gauze and bandages to the team packing and wrapping her wounds. “How’s it going?” Folkes asked Roberts. “Where were you headed?” Anything to keep her conscious, talking, calm.

Twelve minutes later, the paramedics from Central Newfoundland Regional Health Centre pulled up. “When the ambulance arrived, you could hear a collective sigh of relief,” Rodney says. Jennifer stayed with Roberts as she was lifted onto a stretcher and rushed to the hospital. “She was lucky to be alive,” Rodney says. “Regardless of whether they were trained military or medical personnel, everybody had a role to play in saving this woman’s life. We were very proud to be a part of that group.” Once the emergency-room doctors at Central Health had assumed care of Roberts, the Mercers drove home and rushed inside to hug their kids. It was the last time they’d try to take the boat out for the summer.

Danielle and the five friends never did make it to the waterfalls or the Folkes family dinner that night. Instead, they piled into their vehicles, turned around and headed back to the cabin. “We cracked a couple of beers and cooked up some steaks,” Folkes says. “After that, we just wanted to relax.”

Beatrice Roberts spent three months recovering in hospital in St. John’s, N.L. On October 23, 2014, she was transferred back to Grand Falls-Windsor, where her lung, which was punctured, and her back, which was broken in one place, continue to heal. In the meantime, she’s been receiving visits from her 12 siblings and stitching patches for a patchwork quilt that she’ll work on in earnest when she’s fully recovered. She’s still learning the identities of the people who came together to pull her out of her truck. “Everyone was a stranger to me. I don’t know any of them. It really was a miracle,” she says. “I owe those people my life. I wouldn’t be here otherwise. There were a lot of angels there that day.”

Check out more Drama in Real Life from the pages of Reader’s Digest Canada.