The entire puddle was red with his blood…

Aaron Cole couldn’t pass up an adventure, and his girlfriend, Shelly Johnson, couldn’t say no to going along. Driving through New Hampshire on a vacation trip to Baxter State Park in Maine, the couple had already stopped to do somersaults off a lakeside cliff. When they saw Silver Cascade, a waterfall that tumbles down 600 feet in the White Mountain range, Cole had one thought: Let’s climb it.

It was a sunny August day. The college students had set off in bathing suits and flip-flops. Soon they were grappling up the rocks on either side of the falls.

Their ascent was no jaunt – some vertical faces loomed as high as 15 feet. One climbing website cautions that the falls require “a combination of sure feet and steady nerves,” before bluntly warning against the attempt. An experienced climber, Johnson, 22, still needed a hand from Cole, 24. And as with all rock climbing, going up – with the terrain ahead clearly visible – is the easier part.

Just how, Johnson wondered, are we going to get down?

About 45 minutes into the hike and not far from the peak, Cole decided to walk into the falls where they ran over moss-covered rocks. “Please don’t,” Johnson called to him. But she knew Cole: Her concern would only egg him on. Not wanting to give him the satisfaction, she turned away.

When she turned back a few seconds later, she saw that Cole had fallen on his backside and begun sliding down the slick slope. With every moment, he picked up speed and careened toward a sharp drop-off.

For a second, Johnson stared in disbelief. Then she snapped to. “Roll over!” she yelled to Cole. She hoped he could roll his way out of the fast current and get a grip on one of the drier rocks just a few feet on either side of him.

But Cole couldn’t get any traction. As Johnson looked on, he smashed his head on a rock, and his body went slack. Then he disappeared over the drop-off.

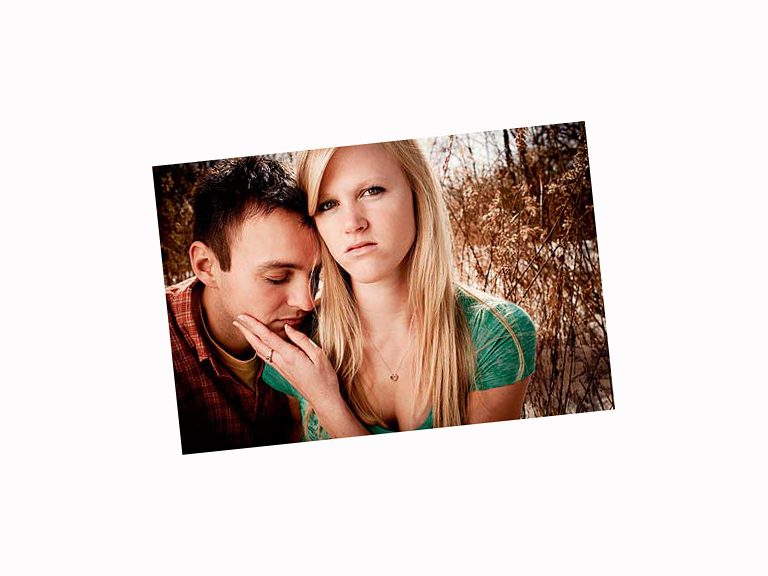

Cole and Johnson met in her senior year at Michigan’s Grass Lake High School. His parents were her coaches – his dad in track, his mom in cheerleading. She and Cole connected the following spring, when he helped his dad at a track meet by refereeing the pole vault, one of Johnson’s events.

On their first date, they went horseback riding and four-wheeling under the light of a full moon. The romance continued in college, where Johnson studies nursing at the University of Michigan and Cole pursues speech therapy at nearby Eastern Michigan University. And they took frequent trips, to wakeboard, snowboard, ride horses, and camp.

It’s always been a happy relationship, Johnson says, with just one sticking point: Cole’s appetite for risk. “Let’s put it this way,” Johnson says. “We’ve been together four and a half years, and I can’t remember the number of times that I’ve taken him to the hospital. He’s never taken me once.”

Johnson had seen Cole fall off horses and crash his snowboard, but those mishaps didn’t prepare her for what happened at Silver Cascade. After scrambling down to peer over the drop-off, she found Cole lying facedown, about eight feet below, in a pool of water. He was thrashing around in spasms. The entire puddle was red with his blood.

Johnson leaped into the water and managed to flip Cole over and drag him to a dry spot. He wasn’t breathing, so she leaned in and gave him rescue breaths, something she’d done many times in CPR classes but never in real life. After the fourth breath, he spit up water, and his chest began to rise and fall. He came to but then quickly fell unconscious again.

With Cole now breathing, Johnson looked over his wounds. Some were obvious. Blood poured from a two-inch gash between his left eyebrow and temple. On the back of his head, there was a lump the size of a goose egg. He also had a deep cut on his forearm.

With her nurse’s training, Johnson could interpret more than what was obvious. Cole’s eyes looked like they were rolling around in his head, and his pupils, she remembers, were “tiny black dots, like the tip of a ballpoint pen” – classic signs of brain trauma.

She could also see that the gash on Cole’s arm was dangerously close to the radial artery. If he had nicked it, he could die.

The two had left their cell phones in the car, and there was no one else in sight. Johnson, knowing she was a long way from help, faced an agonizing decision. Should she try to get Cole down the treacherous path by herself? If he had a spinal cord injury, moving could paralyze him. But if she left him there, she felt sure, he would bleed to death. “I can’t just leave him,” she concluded.

“Stay with me,” she kept telling Cole. “Stay with me.”

Johnson knew Cole’s wounds needed bandaging, but she had nothing except the clothes she was wearing – a pair of black surf shorts and a bikini. First she took off her shorts and wrapped them around his head like a tourniquet. But what about his arm wound?

“That’s when the swimsuit top came in handy,” Johnson says. “And there was no second where I thought, People are going to see me without my top on. When you’re in that situation, you’ll do anything. My bikini bottoms would have been off if I’d needed to.”

Johnson still struggles to explain how she did what came next. At five feet six inches, she weighs 115 pounds. Cole is four inches taller and weighs 160. Ordinarily, she can’t lift him for even a few seconds. But in the adrenaline rush after the accident, she was able to wrap Cole’s arms around her shoulders, reach behind her to grab his legs, and begin to make her way down the rocks. To descend the vertical faces, she had to slide her bottom and inch her way down, pressing hard with her back to pin him to the rocks.

“Stay with me,” she kept telling Cole. “Stay with me.”

She yelled for help, but the roar of the waterfall drowned out her voice. It’s like a nightmare, she thought: I’m screaming, but no one can hear. As she neared the bottom, about a half mile from the place where Cole had slipped, Johnson called out to a group of people milling around the trail near a natural wading pool. “Help us!” she cried.

Behind the wheel of his Jeep Grand Cherokee, Vernon-John Gibbins was driving on New Hampshire’s lush, isolated Route 302 when a police car whipped by and pulled over to the side of the road. A critical-care nurse, Gibbins was on his way to Maine’s Camp Cedar, where he spends his summers running the health center.

When Gibbins saw the police officer rush across the road toward the falls with a first aid kit, he stopped his Jeep and ran to join the group standing around Cole, who was weak but conscious.

“You’re going to be fine,” Gibbins told Cole after checking his head and arm wounds. But he wasn’t so sure. Another hiker, one from the wading pool, had called 911, but how long would it take an ambulance to arrive in rural New Hampshire? As they waited, Johnson, who had retrieved a dress from the car, talked softly to Cole and held compressions on his wounds. But within minutes, Cole went from being calm and coherent – he knew his name and that he’d been in a climbing accident – to fighting three men who then had to pin him to the ground. Gibbins recognized the telltale signs of an internal head bleed, which puts pressure on the brain and sometimes makes victims disoriented and aggressive.

After 15 minutes, an EMT arrived in an ambulance, but he didn’t have the training to administer a sedative to Cole, which was necessary before inserting a breathing tube. Without intubation, Cole couldn’t be transported, because he might stop breathing on the way. The EMT called a paramedic for help.

By now, Cole was slurring his words and still throwing punches. But even then, says Gibbins, he always seemed to calm down at the sound of Johnson’s voice. She knelt by him, holding his hand and stroking his hair, telling him, “I love you,” and, “Lie still.”

It took another 15 minutes for the second ambulance to arrive. The paramedic quickly gave Cole a shot of a sedative and inserted a breathing tube. But after a few minutes, Cole woke up and began to grab at the tube.

They were losing precious time. So they decided to carry Cole – despite his thrashing – across the rocks and through the weeds to the ambulance.

Thirty minutes later, they neared Littleton Hospital. “We’re almost there,” the driver called out.

Thank God, thought Gibbins, who had accompanied the couple. But he worried the small facility might not be equipped to handle this kind of trauma.

At the hospital, the medics rolled Cole into the emergency room. There doctors quickly called for a helicopter to take him to Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center in Lebanon, where he could be evaluated by a brain surgeon. When Gibbins glanced at himself in the mirror in the ER bathroom, he saw that he was covered head to toe in Cole’s blood.

At Dartmouth, Johnson spent the night on a couch in Cole’s room. When she woke up, she immediately felt her exertions of the day before. “I’m a track runner, and I’ve been sore from lots of different things,” she says. “But I literally could not move.” And she was so hoarse that she could only whisper. The physical pain was compounded by worry.

Doctors kept Cole in an induced coma for two days, hoping that the swelling in his brain would recede. The medical team couldn’t predict what his condition would be when he woke.

Johnson was still at his bedside when he did. The doctor told him to wiggle his toes, and he did. Then Johnson used one of their private signals: They hold up their fingers in a one-four-three pattern – first the pointer finger, then four fingers, then three – their way of saying “I love you.”

When Johnson signaled, Cole lifted his hand and did the same, and Johnson melted with relief.

She wasn’t the only one. As soon as Cole could talk, Johnson called Gibbins’s cell phone. “I have someone who wants to say hello,” she said.

Then Gibbins heard a young man’s voice. “Hey, buddy,” Cole said, and Gibbins broke down crying.

“I know that something led me to be on that road at that exact moment to be able to help him,” Gibbins says.

Not only did Cole escape brain damage but he also came through the experience with only scars on his arm, leg, and forehead. “He calls them his warrior scars,” Johnson says.

Cole doesn’t remember much of what happened after he slipped. But he does recall Johnson telling him not to walk in the water. “I think after this, we’ve settled down a little bit,” Cole says. “It knocked a little bit of the daredevil out of me.”

Johnson holds out hope that in the future, “there will be times when I’ll say to him again, ‘Aaron, don’t do that,’ and maybe he’ll think twice.” She can’t account for how she carried him down the mountain. “I look back and think, How in the world did I do that? It definitely makes me feel like there are powers out there stronger than mine.”

Check out more Drama in Real Life.