Leap of Faith

On March 18, 2017, Verna Marzo awoke in her Calgary apartment with crushing abdominal pain. It was 4 a.m. and the analgesic she took did nothing to ease her suffering. Her roommates decided to drive her to the nearest emergency department.

The 44-year-old had been living for a year with a cyst that doctors had discovered pressed up against an ovary. It was likely benign and would shrink on its own, she was told. But at the hospital, tests revealed that the cyst had grown to the size of a grapefruit. Worse, Marzo’s pain and fever suggested it might have ruptured. Knowing she would need emergency surgery, doctors ordered her transferred to Foothills Medical Centre by ambulance.

The chief physician on call that night recommended a full hysterectomy. Marzo, who wanted the ordeal to end, consented emphatically—“Get it out!”—and was whisked to an operating room.

By morning, with the surgery completed, Marzo was recovering in the intensive care unit, but something was still wrong. She had a raging fever and her abdomen was distended. When ICU physician Dr. Paul McBeth arrived for his shift at 8 a.m., he scrutinized her file. Taking out a cyst is a fairly straightforward operation, he thought, but she’s clearly in shock. “We’re missing something,” he told his residents.

Marzo’s sister Debie, who had been at the hospital the night before, gasped when she parted the curtain to visit again that morning. Marzo had ballooned overnight due to fluid leaking from her blood vessels. Her sister, it struck Debie, had “tripled in size.”

Meanwhile, Marzo’s blood pressure had crashed, her tissues were oxygen-starved and she was breathing with the help of a ventilator. Doctors chose to put her into a coma so her body wouldn’t have to work so hard, and gave her high doses of broad-spectrum antibiotics to combat infection.

Marzo’s body was in shock, but there are many different kinds of shock. The doctors went into detective mode. McBeth peppered Debie with questions in the family waiting room. Had her sister been travelling? Did she have any allergies? Could she have overdosed? What was the family history?

A Life-Threatening Diagnosis

Marzo had never been less than a storm surge of energy. As a young girl in the Philippines, she loved sports—running and surfing especially—and her playful hijinks were contagious. She is the second-oldest among four siblings in a fun-loving family for whom, as she puts it, “every day is April Fool’s Day.”

To raise money for his children’s education, Marzo’s father left their village, La Union, to work in a factory in Saudi Arabia when Marzo was six years old. At age 28, Marzo decided to return the favour, leaving a marketing job in her hometown to seek employment abroad. That quest led her to Calgary in 2001, where she worked as a nanny and then started her own cleaning and interior-design business.

Marzo’s parents stayed in close touch through Skype as their daughter learned to navigate the culture, to overcome her shyness and to soften her blunt Filipina English with common Canadian idioms. She found an evangelical church community full of kindred spirits, one that her sisters Debie and Luela joined when they followed her to Calgary several years later. Things went smoothly in her new home—until they didn’t.

Some 18 hours after Marzo arrived at Foothills, McBeth’s initial fears were confirmed: Marzo had sepsis, massive inflammation that was triggered by E. coli in her bloodstream. Exactly how the bacteria got into her system—whether from inside the hospital or elsewhere—will never be known.

Septic shock is a grave complication, a flash flood that can overwhelm a body in 12 hours. Only about half of those who contract it survive.

The doctors had a near-impossible balancing act on their hands. One symptom of the condition is runaway blood clotting, so blood thinners were issued. But those can trigger internal bleeding and lower a patient’s blood pressure. The drugs used to counteract that effect starve the tissues of oxygen. Meanwhile, Marzo needed to be kept in a coma, but sedation could drive her blood pressure even lower. Cardiac arrest was a real threat.

Sure enough, Marzo flatlined—twice within a couple of hours. McBeth and his colleague, Dr. Jason Waechter, took turns resuscitating Marzo by giving her intravenous doses of epinephrine.

“I’m afraid it’s hour-to-hour now,” McBeth told Debie and some close friends who had gathered in the waiting room that evening. “We need to be prepared for the worst.”

Marzo’s kidneys had shut down. There were blood clots in her lungs and capillaries. McBeth hardly left her bedside the entire night.

In the morning, McBeth met again with Marzo’s circle of support. “The likelihood of survival in the next hour is very, very low,” he told them. He doesn’t like to give exact probabilities, but when pressed, he guessed she had less than a 10 per cent chance of survival.

As her condition worsened and her likelihood of making it shrunk even further, Debie texted loved ones who couldn’t be there, asking for prayers. In the Philippines, Marzo’s mother applied for an emergency travel visa.

Read about the car crash victim who survived internal decapitation.

Her Only Chance of Survival

If a person’s odds of surviving are linked at all to their passion for this world, then the doctors had underestimated Marzo’s chances.

At age six, she experienced her first great thrill, jumping from a bridge into the local river. Thirteen years after arriving in Canada, she took a much bigger jump—this time tethered to a skydiving instructor—over the canola fields of Innisfail, Alberta.

Then, one day five years ago, Marzo found a companion for such exploits: Leah Escabillas, a young woman who showed up at Marzo’s church. Escabillas had emigrated from Saudi Arabia, where life for women is stiflingly proscribed. Marzo sensed a fellow traveller in Escabillas, someone whose hunger for adventure matched her own.

The two started planning trips together, which grew into a series of ongoing experiments in endurance and adrenalin. They went on snowshoeing and hiking expeditions. They cage-dived with great white sharks off of Cape Town.

Then, in 2016 they decided to bungee jump from Victoria Falls Bridge, on the border of Zimbabwe and Zambia. As Marzo stood more than 100 metres above the Zambezi River, with Escabillas close behind, it was clearer than ever to her that she’d found someone to share her mission to live right to the edge of her skin. You do this because it scares you, they agreed. You go out on a limb because that’s where the fruit is.

“Five, four, three, two, one, bungee!”

Marzo didn’t die the day after her emergency surgery, or the one after that. But on day five, her family received more bad news. Marzo’s arms and legs were ischemic: oxygen-starved. The resulting dead tissue could spark a release of toxins throughout her body that would kill her unless something radical was done.

She was eased off her cocktail of sedatives, paralytic medications and anti-anxiety meds, and quickly surfaced from the coma. The next day, with a half-dozen people crowded around Marzo’s bedside—including Debie, Luela, the hospital chaplain and Charles Coleman, a close friend—McBeth laid out her options.

“Your best chance of survival is with amputations,” he said.

It was her call, he emphasized, but if she opted to go ahead, there was no time to waste. In every limb, the ischemia was quickly spreading toward the joint, so any delay meant potentially losing a chance at prosthetics.

If ever a moment called for Marzo to be decisive, this was it. She was on life support, with a breathing tube, but she could still nod and shake her head.

Five, four, three, two, one. Marzo gave McBeth the go-ahead.

Find out how a complete stranger saved a dying girl’s life.

A New Life’s Purpose

On April 4, one day after two rounds of amputations, Marzo slowly came to. Alone in her hospital room, she looked down and saw her bandaged and shorter right arm. No left arm. Lower down, there was the disorienting outline of her diminished legs under a cream-coloured blanket.

For the first time she felt a darkness engulfing her. As a person of faith who has always found guidance in prayer, she made a request to God: “I’m sure there is another person here in this hospital who is not long for this world but wants desperately to live,” she said. “I’m asking you to let them live and take me instead.”

But when the days continued to pass, and she did not get her wish, she started a different conversation.

“Looks like I’m here to stay, at least for now. I wonder why.”

As social workers and psychologists prepared her for the inevitable crash in her spirits, it occurred to Marzo that perhaps she had found a new life’s purpose: to not be that person who gives up.

“Okay,” she said to herself, “Let’s do this.”

A name was coined for the growing group of front-line support gathered in Marzo’s corner: Team Verna. Beyond her close friends and family, it also included a physiotherapist and a social worker. Someone was always around to sing to Marzo, tell a joke or gently lay a hand on her in prayer. Anchoring Team Verna was her mother, who had arrived at Marzo’s bedside on April 1. (Marzo’s father, who was recovering from a heart attack, remained in the Philippines).

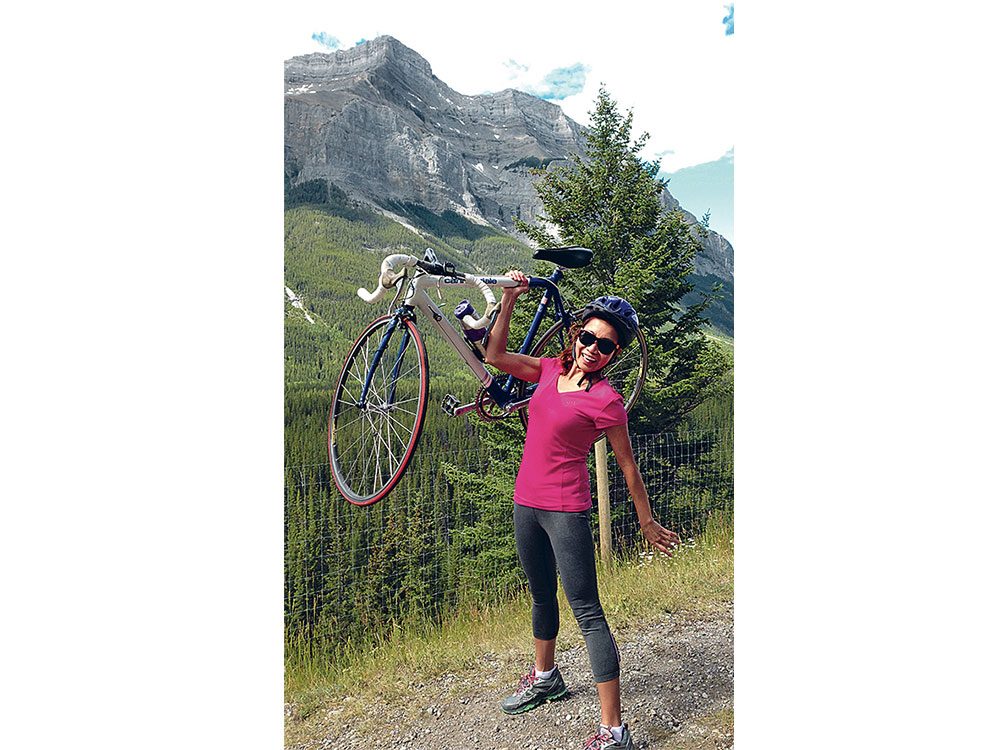

The walls of Marzo’s private room became adorned with photographs of her dangling over some precipice or free-falling from the sky. These images weren’t for her benefit, though—they were for her caregivers. “When they come to treat this person, they see her as a survivor, a thriver—not someone who elicits pity,” Coleman says.

Little by little, Marzo’s body started repairing itself. She’d lost her hair and eyelashes; they grew back. Blood clots had riddled her body and her brain; they dissolved. “She probably has some element of permanent kidney damage, but her kidneys function. Her liver functions,” says McBeth.

Then, one morning in late May, a nurse looked in on Marzo.

“How’re ya doing, girl?”

There was no response. The nurse leaned right into her ear. “Verna?” Nothing. The nurse’s face became clouded with concern.

She summoned the doctor on the ward. Both of the caregivers worriedly checked her vital signs on the monitor, looking for clues.

Suddenly Marzo’s eyes popped open. And she broke into a smile. The tension was shattered, and everyone laughed.

A surgeon performing an amputation will try to save as much of a limb as possible. Sometimes they will leave it a little long, then go back, if necessary, and take more. “We need to salvage enough tissue to ensure we can close the wound site to provide a functional limb,” McBeth says.

Discouragingly, Dr. Rick Buckley, the orthopaedic surgeon who performed the amputations, had to open Marzo up four more times during the second week of that May—ultimately reducing her left arm to no more than a stub and, devastatingly, cleaving off the right leg above the knee.

To live in her new body, and function day by day, Marzo had to relearn how to eat, go to the bathroom and even sleep. “It’s like being a baby all over again,” she says.

Around that time, Marzo’s prosthetic legs arrived at the hospital. Walking on them required her full concentration—and it took training. “There’s a lot to think about just to stand,” Marzo says.

But she was the most ferociously committed rehab patient her physiotherapist, Erin McDiarmid, has ever seen. “Verna out-planks everyone,” she says. “And out-crunches the trainers.” Determined to be ready for hiking by the summer, Marzo insisted on practising over uneven ground.

In August, Marzo’s fibreglass right arm was ready; it fit to her stump by suction. Impulses from forearm-muscle contractions are conveyed to hydraulics in the five-fingered hand so that Marzo can signal it to open or close simply by thinking those words.

“I can eat!” she proclaimed the first time she tried it. “I can brush my teeth!”

And then, after that: “I can rob a bank! No fingerprints!”

Growing up, Marzo had never seen an amputee. “In my village there were none,” she says. “If someone lost a limb in a farm accident, they’d probably die because they couldn’t work and make money.” Even after arriving in Canada, she only recalls encountering one amputee, in church.

On December 7, 2017, after 263 days in hospital, Marzo was transferred to the Carewest Dr. Vernon Fanning Centre, a long-term-care facility in northeast Calgary. Here are the amputees, she realized.

Marzo found the mood inside sombre. Ambitions were banked, and Marzo noticed that most of the patients were relying on the aides for everything. “They’re becoming dependent on them,” she says. “But I know they can do more.”

There was a gym in the facility, but few went. As Marzo performed her exercises with focus and dedication, her effort became an inspiration. Other residents started showing up, and Marzo lavished them with praise. Before long, the gym was full and, among residents, workout time became known as “happy hour.”

At the end of March 2018, Marzo decided to enter a 5K race taking place in Calgary that summer. But the day before the event, there was a setback with the prostheses. She had just received a new fitting for her right leg, and, no matter how Debie attached it, the pain was unbearable. Marzo was incandescent with frustration. She can’t do this, she told Debie. She’s pulling out of the race.

“Okay,” Debie replied. “But why don’t you just go anyway? We’ll bring your chair. I can always push you.” Marzo let a long silence hang in the air after her sister’s offer. Then she asked: “Where are you planning on eating after?”

On July 21, Marzo never needed the wheelchair. She walked the entire five kilometres and approached the finish line to cheers and the promise of a victory burger and shake on Debie’s dime. After she crossed the line, Escabillas enveloped her in her arms—and planted a tantalizing idea. The Honolulu Marathon takes place the second Sunday in December each year. “Let’s do it together,” she said.

In the ensuing months, Marzo spent as much time as she could on the treadmill to build up her aerobic base. Periodically, she landed back in hospital with bowel obstructions—fallout from the scar tissue—but after each complication, she focused again on her goal.

Then fate dealt yet another blow. On August 18, 2018, Marzo learned that Escabillas had been hiking a high ridge on the flank of Mt. Rundle in Banff, Alta., when she slipped and fell. Escabillas was rushed to hospital but pronounced dead on arrival.

For Marzo, the news was devastating. After Marzo’s tragedy, Escabillas had not given up on their adventures, even arriving one day to go snowshoeing, carrying a sled on which to pull Marzo. But now she was gone.

In the days that followed, Marzo realized she didn’t want their Honolulu dream to die. She wouldn’t be able to run the race that December, but would aim to do it by 2020. If running a marathon is a feat more of heart than head, more of soul than body, then it will be no problem. And Escabillas will be right there with her still. They’ll do it together.

“Team Leah,” says Marzo, raising her right arm in salute.

Next, read about how a woman’s cousin saved her life with the ultimate gift—an organ donation.