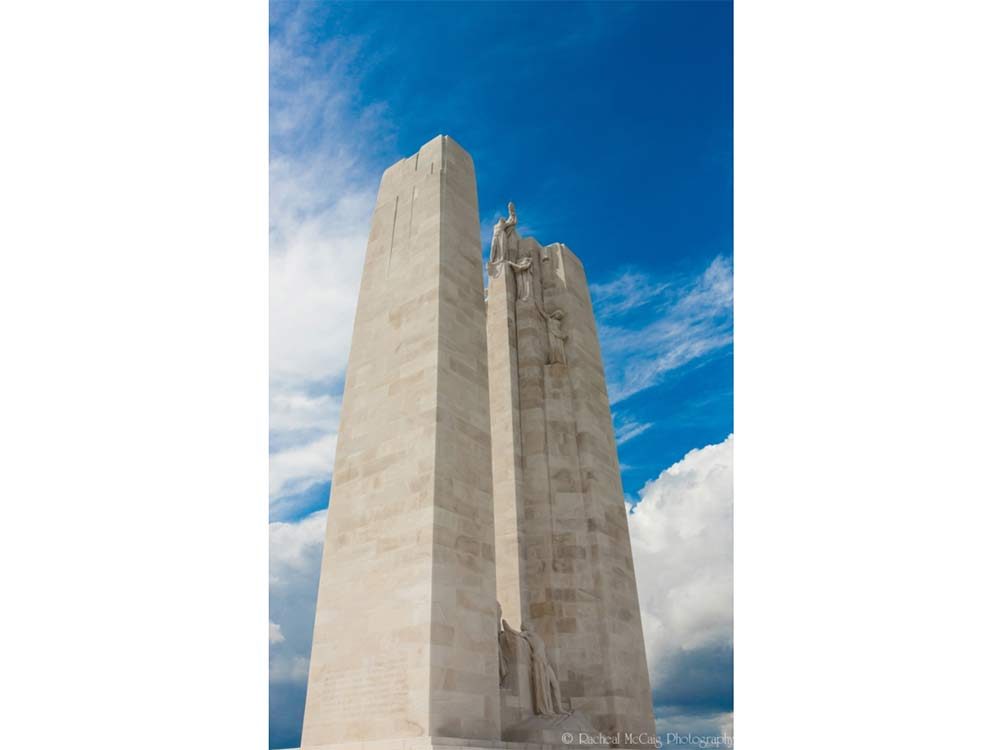

The 100th Anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge

Designed by renowned Canadian sculptor Walter Seymour Allward in 1921, the Canadian National Vimy Memorial’s twin pylons represent Canada and France, and pay tribute to the 3,598 Canadians who died there, as well the 7,000 Canadians that were injured during battle.

Canadian photojournalist Racheal McCaig first visited the memorial—located in Givenchy-en-Gohelle—in 2014 with her children, and the experience made a lasting impact. “The sense of Canadian pride really hits you, but also the sense of tragedy and what those soldiers sacrificed,” she says. Now, a series of photographs she captured in 2016 will be exhibited in Canada and France as part of the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge on April 9.

Her exhibit, Je Me Souviens: Vimy 100, will showcase 18 photographs of the monument and its surrounding trenches, and is an integral part of the official ceremony marking the centenary. Starting in June, McCaig’s exhibit will tour select cities in Canada. “It’s about giving Canadians the chance to see what we accomplished at Vimy Ridge,” says McCaig. “Whether or not you agree with why Canada fought, the reason our opinion and freedom exist today is because we did fight.” Here’s a sneak peek of McCaig’s photography, which will have you seeing the iconic image on the back of our $20 bill in a whole new light.

“A vous nous lancerons le flambeau”

This striking photograph captured the attention of Pierre Senechal, mayor of Givenchy-en-Gohelle, who later requested that McCaig’s work be part of the official ceremony. “It was pouring rain, and I first saw the monument as the skies cleared,” she says. “I knew I needed to capture this moment, and figured that this was the best way to present it.”

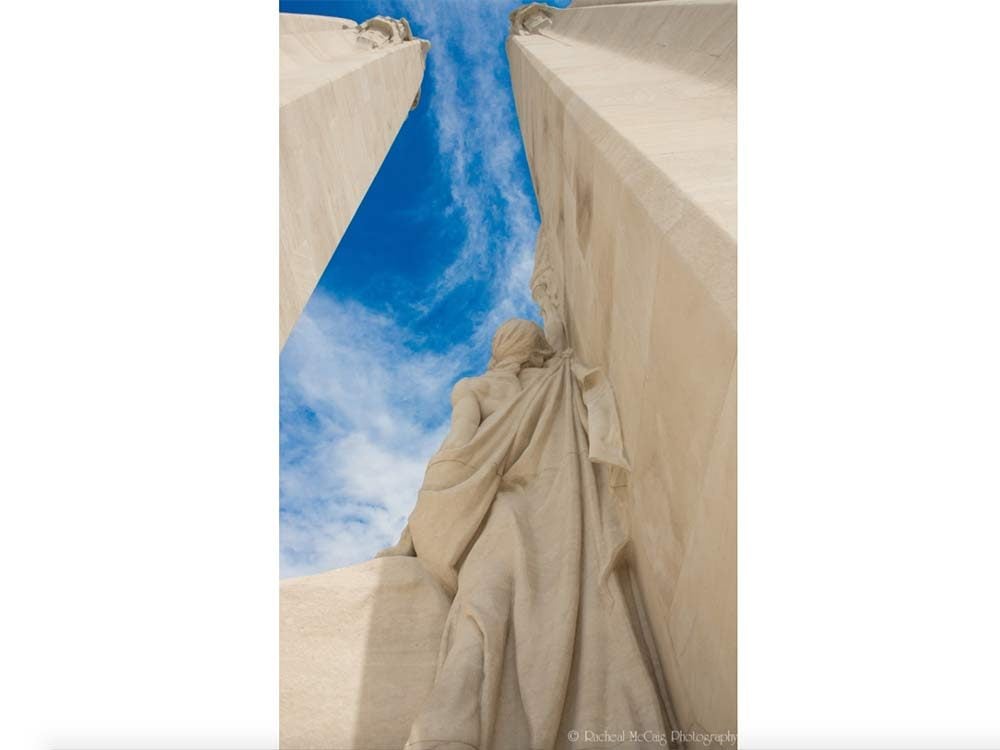

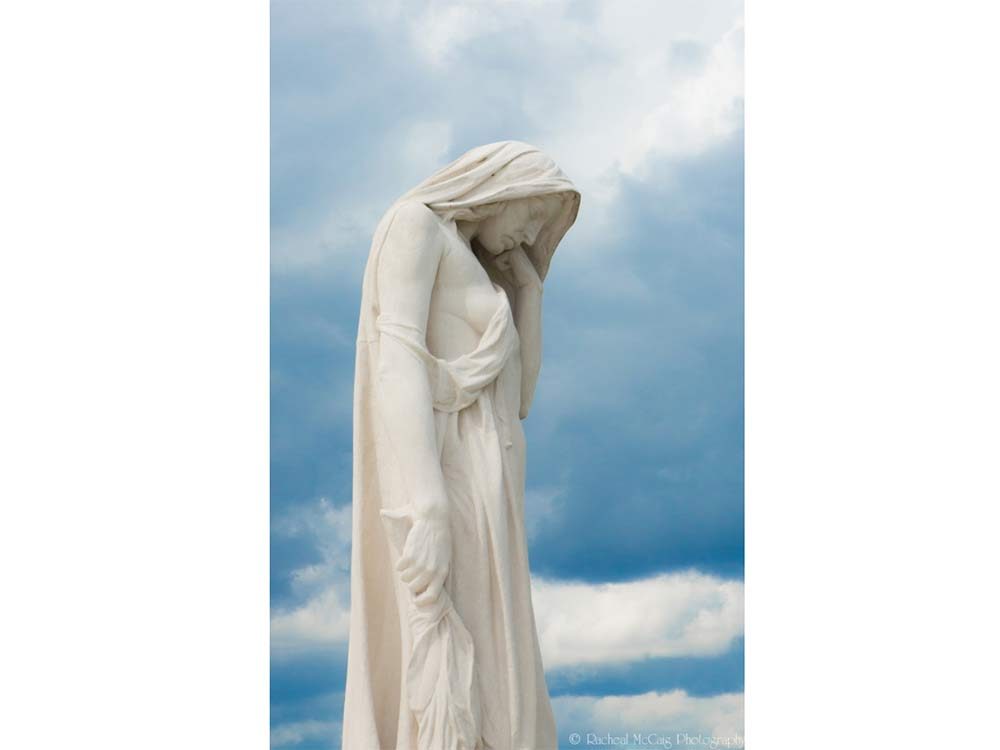

“La femme qui pleure”

“This statue goes by several names, including ‘Female Mourner,’ ‘Weeping Woman,’ and “Canada Mourns,'” says McCaig. “It’s a tribute to the price we paid during the battle, and is sculpted out of a single block of limestone.” The statue is located on the left side of the stairs leading up to the monument, and was carved on-site. According to McCaig, the original model for the statue was a dancer-turned-model by the name of Edna Moynihan, and McCaig had the opportunity to meet her surviving daughter.

“Une vue a une mise”

“With this image, I wanted to show the gunner’s sight during battle and accurately depict the distance from which Canadian soldiers saw the enemy,” says McCaig. Many new platoon tactics were implemented by the Canadian army during the Battle of Vimy Ridge—troops were ordered to move constantly, outflank enemy machine gunners, and use grenades and follow-up with bayonets. Canadian Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew McNaughton also used brand new optical and acoustic techniques to locate enemy guns. These tactics solved many of the challenges inherent in trench warfare.

“Nous nous souviendrons”

According to McCaig, this photograph depicts one of the few unknown graves at Vimy Ridge. “The Canadian cemetery is located next to the memorial, and I saw each of the headstones row by row,” she says. “It made the battle that much more tangible.” Percy Moore of Carleton Place, Ont. was the youngest soldier she found—having lied about his age at the time of enlistment, he was 16 when he died at Vimy Ridge. Albert Williamson, 39, a clerk in Prince Rupert, B.C., was the oldest.

“Le chemin de la victoire”

A labyrinth of underground bunkers, the Grange Subway was the main tunnel Canadian soldiers used to sneak under enemy lines and execute their successful surprise attack on April 9th, 1917. “We nowadays don’t realize what this network was really like,” says McCaig. “It’s small and narrow, yet filled with train tracks, lighting systems and storehouses.” Stretching 800 metres in length, features of the tunnel also included command posts, hospitals, water reservoirs and communication centres.