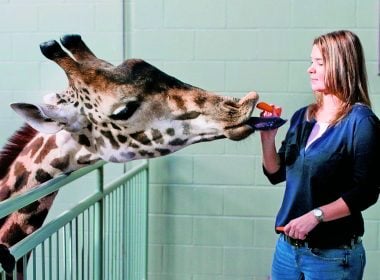

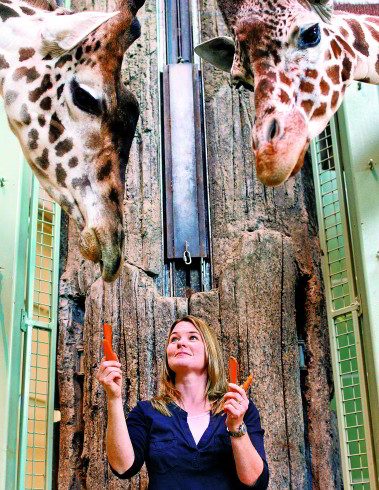

In the 19 years she has been at the Calgary Zoo, Carrie the giraffe has delighted legions of children with her gentle nature. Her physical abilities and survival instincts, though, are still as sharp as those of any giraffe in the wild on guard against predators. A mother of three, Carrie can run at speeds of up to 50 kilometres an hour, and the karate-style kicks of her nearly two-metre-long legs could take off the head of a lion.

When flood waters filled her pen up to her belly and the terrified Carrie charged, Jake Veasey knew his life was in danger. The zoo’s 42-year-old director of animal care, conservation and research dodged the animal’s flailing legs and jumped off a ladder into the water. As he did, he pushed one of his colleagues out of harm’s way. Everyone was safe-for the moment. Together, man and beast were battling the June floods. The zookeepers prayed the tale would have a happy ending.

“Man, I’ve just boiled my soup,” he said half-jokingly as he answered his phone. On the line was Jamie Dorgan, 36, the zoo’s general curator. “There’s a flood alert,” Dorgan told his boss. Veasey needed to get back there right away.

As he grabbed his keys, Veasey had no idea an entire week would go by before he returned home. He pictured a few centimetres of water, not an unusual situation for St. George’s Island, the 13-hectare islet in the Bow River that was home to, not including fish, 215 of the zoo’s animals.

He wasn’t alone in his optimistic assumptions: Darryl Dziadyk, the 49-year-old head of zoo facilities, wasn’t troubled either. But by 10:30 a.m., he’d received a phone message requesting his presence at the city’s emergency operations centre. Upon arrival, Dziadyk-who had been working with city officials on improving emergency preparation procedures for the zoo-learned this wasn’t going to be an ordinary flood.

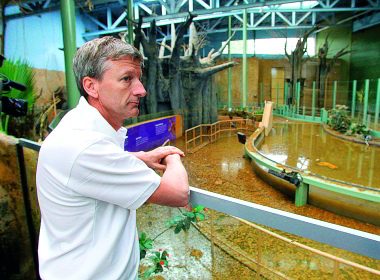

On a conference call to key zoo personnel, Dziadyk broke the news: the flow rate of the Bow River could exceed 1,800 cubic metres a second. That was much higher than the river’s rate during the deluge that devastated the zoo in 1929. On the other end of the call, the zoo supervisors watched intently as one of the facility managers spread out a flood map. “Is everyone looking at the map?” asked Dziadyk. “Everything red is going to be underwater.”

Ninety per cent of St. George’s Island was crimson. “There are only two small areas that aren’t red,” said Josh Watson, an eight-year employee. “Is this for real?” For Veasey, what mattered most was how deep the water would be in each of the buildings. “There’s a big difference between three centimetres of water and three metres,” he said. But with no way to quickly and accurately determine how high the water would reach, Veasey couldn’t assume anywhere was safe. They had no choice but to evacuate as many animals as possible. The zoo staff didn’t know it, but they only had 10 hours before the flood would hit the island, endangering more than 200 animals. The evacuation plan bordered on impossible. Getting upset about it, though, was a luxury no one could afford.

Some of the tasks in the first few hours were straightforward, if a bit unwieldy: Malu Celli, a Brazilian with a PhD in animal behaviour, found herself handling sloths for the first time; 30 flamingos were scooped up and moved in a matter of minutes; the goat-like serows were herded and loaded into a horse trailer, its driver spending hours commuting between the zoo and its Devonian Wildlife Conservation Centre, known to personnel as the ranch, south of the city.

Other tasks were not so simple. Six Amur tigers had to be tranquilized with blow darts. Normally, it would take half a day to anaesthetize and transport just one tiger. As each one went down, the others became increasingly distressed. Moving the bull elk with its massive antlers was also not for the faint of heart. “Whoa, this is crazy,” said one of the helpers to Dorgan, as a dozen men rustled the elk into a trailer. “This is not crazy yet, guys,” replied Dorgan.

Animal-health technologist Lori Rogers couldn’t believe the flood’s timing. The animal-health centre had opened its $1.2-million renovation just three weeks earlier. “If the flood had come any sooner,” she says, “there’s no way we would have had handling space for all these animals.”

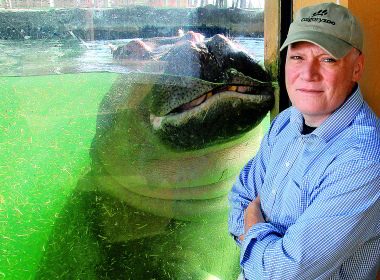

The centre could accommodate 60 animals comfortably but was on its way to 150 as night fell. While some were moved around in the zoo and others were shipped to the ranch, several animals had to be left in areas deemed safe for the time being. Lobi and Sparky, the zoo’s hippopotamuses, were water creatures, so they were secure in the African Savannah building; the gorillas could climb into what was known as the Sunshine room, an upper area of the Rainforest building; and the camels were on high ground, albeit on a small patch of land.

It wasn’t possible to move the four Asian elephants in such a short time, considering all the more susceptible animals needing evacuation. It was hoped that the elephants were big enough and on high enough ground to survive even serious flooding.

At 2:30 a.m. on Friday, Veasey, area curator Colleen Baird, Celli and Watson surveyed their sleeping quarters at the Discovery Centre. “You caught all the macaques?” Veasey asked Celli. Normally, his zookeepers wouldn’t catch more than one macaque a day. Listening to the inventory of animals rescued, he felt immensely proud of his staff, who had kept their cool.

The flood is coming, there’s nothing more we can do, Watson thought to himself as he closed his eyes. Veasey still dared to hope that it would all be for naught come morning, that they’d wake up to a simple cleanup operation. “Guys, you need to come see this.”

Watson stood over Veasey, Celli and Baird as they lay in their cots, still in the dirty clothes they’d worn the day before, their bodies warmed by covers and throws from the gift shop next door.

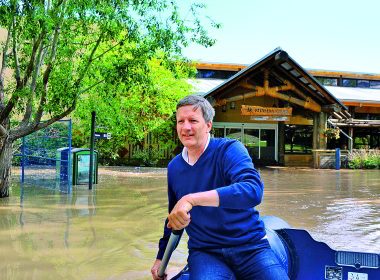

Please let me sleep a little bit more, Celli thought before she was awake enough to recognize the alarm in Watson’s voice. Within minutes, all three headed outside. “How the heck are we going to get anywhere?” said Baird as she scanned the water that had almost completely swallowed the island in just over two hours. Baird got on the phone to Dziadyk. “We need boats.”

Not content to wait, they made their way-from one dry patch of ground to another-to the Rainforest building. All six gorillas were alive and well, so Celli and Watson ensured they had enough food before heading to the Savannah building.

Unable to open the doors, Watson grabbed a rock and smashed a window. Once inside, they saw the water was rising fast and would soon overtake the meerkat enclosure. After a few confusing seconds, Celli realized all five of the squirrel-sized animals were cowering inside a long, concrete log.

Knowing that meerkats can inflict bites, Celli nonetheless reached in to try to coax them out. No deal. The pair tried tipping the log into a crate, but the terrified quintet wouldn’t budge. So they carried the log through the knee-deep water to the keepers’ kitchen. Watson stuffed an empty garbage bag in one end and taped it; the other end was jammed with a Rubbermaid garbage can. Watson carried the log on his shoulder and handed it through the broken window to one of the zoo’s directors who’d come to help.

A few minutes later, Rogers woke to the sound of someone tapping on her office window. It was two of the grounds crew with the meerkat log. “Okay, okay, where am I going to put them?” Rogers wondered aloud as she looked around her building, which now resembled Noah’s ark.

The building didn’t look good from the outside: the water came almost to the top of the exterior doors. As they tried to determine just how they were going to get inside, Veasey took his paddle and pointed toward a window below.

“Colleen, I can put my whole paddle in,” he said, demonstrating the gap in the window. The two looked at one another with horror in the realization that they were in a potentially life-threatening situation.

Spotting a straw-filled shipping container floating nearby, Veasey was inspired. If he could wedge it against the window, perhaps he could enclose the errant hippo. With a wary Baird at the ready with her tranquilizer rifle, Veasey climbed onto the container and guided it between two concrete posts outside the window. Despite his hands being numb from the frigid water, he tied knots in slots on top, securing them around the posts.

Watching the container bob in the water, a shivering Veasey figured a determined hippo wouldn’t have much trouble simply pushing it out of its way. “We need to sink this thing,” he said to Baird before opening the doors of the container. As he did, water rushed inside, wedging it in the precise spot needed to block the opening. A crisis averted, both thought, but they still didn’t know if the other hippo had managed to shimmy its way free before their arrival.

At the south end of the Savannah building, the giraffe pair, Carrie and Nabo, stood shivering in more than two metres of water, up to their bellies. With every hour they remained submerged, their chances of survival diminished.

Just getting near them was a challenge. With the power out, none of the automatic doors worked. After a few failed attempts, Dorgan, diving under the water to try various keys, finally got the exterior door open. They now needed to persuade the giraffes to go through a corridor and a water-filled chute to the open air. It was a long shot: the chute was a loading area, typically used by humans. The habit-loving giraffes wouldn’t venture there during the best of times. In the wild, there might well have been crocodiles lurking under the surface. But there was no other option. The giraffes, skittish and suspicious, were having none of it. Spotting plastic picnic tabletops floating in the water, Veasey enlisted Baird and Dorgan in a last-ditch effort. The three donned dry suits and hockey helmets-used by keepers working with the spiral-horned markhor goats-then made their way along the water-filled hallway, using the tabletops as shields. No amount of yelling, though, could convince the giraffes to move. Flares attached to the ends of sticks had no effect. The three were on the losing end of a standoff.

It was at this point that the distressed giraffes reacted wildly. Veasey, who had climbed a ladder to try to coax the animals forward, had to jump into the water to get out of the way of a charging Carrie. As he fell in, Veasey grabbed Baird, who was far too close to the panicked animal, and, using all the strength he could muster, shoved her out of Carrie’s path.

Over the coming days, the curators and their boss would face more challenges: the animals were not in their appropriate facilities, food rations were low, and the power was out for weeks. But there was some good news: they were able to see that the two hippos were still inside Savannah.

On Saturday night, Veasey and Dorgan continued to care for Carrie and Nabo, feeding them as best they could. By Sunday, the receding waters opened an alternate route to safety, one the giraffes were willing to try. Watching the beautiful animals warm up in the midday sun, Dorgan thought, I won’t relax until they’re still alive a month from now.

A month later, Carrie and Nabo were still alive, showing no signs of permanent harm. Their survival, along with that of more than 210 other animals on the islet, is a credit to the perseverance of zoo staff. For his part, Veasey downplays any personal heroics. “The support we received from the entire city was phenomenal,” he says. “The zoo is symbolic of Calgary’s recovery.”