The Architect Who Went From “Starchitect” to Humanitarian

Yasmeen Lari designed gleaming towers for Pakistan’s corporate elite. She now rebuilds villages devastated by natural disasters.

As Yasmeen Lari looked out the car window across the Siran Valley in northeastern Pakistan, she grieved for what was no longer a lush vale with rolling green hills, trees and mountains. It was 2005, and the catastrophic earthquake that had killed as many as 79,000 people in Pakistan, India and Afghanistan one week earlier—on October 8—had reduced the valley to mud, rubble and flattened buildings.

The 65-year-old architect was there to help lead the reconstruction of settlements, but she had never done disaster work before. Lari was filled with anticipation after a two-hour flight from Karachi to Islamabad, Pakistan’s capital, followed by this five-hour drive.

Darkness had fallen before her driver pulled into a dimly lit army camp where the military rescue operation was based; at 1,500 metres it was safer from aftershocks and rock slides than lower ground. When she stepped out of the car she was taken to the commanding officer, who talked to her about the villages that needed immediate help. The enormity of the task ahead hit her full force.

Lari, who had become Pakistan’s first female architect in 1964, was renowned for designing slick towers of glass and concrete in Karachi. But here, she’d be drawing plans for earthquake-resistant homes using stone and timber debris. Working from a rough cottage near the camp, she’d spend the next four months working with volunteer architects and engineers from Pakistan and abroad.

She would send her drawings with the volunteers, who walked through difficult terrain to reach mountain hamlets. There, they’d assist displaced families with sorting debris and building new and improved homes, even as temperatures plunged and snow began to fall.

“You can’t imagine the desolation,” Lari recalls of those early days in the mountains. Her team members, often the first people to arrive on the scene, were greeted with unexpected hospitality, given the circumstances.

On one visit, villagers pulled out their best salvaged chairs and table. “They had lost everything,” she says. “But they put this damaged table in front of us and covered it with a beautiful embroidered cloth. And then they served us their World Food Programme food: biscuits, tea and eggs.”

With each passing day, Lari was re-engineering her identity—from “starchitect” to humanitarian. The profession had been good to her, but she had become disillusioned with projects for corporate elites. And doing disaster-relief work felt deeply right. So she made it her new mission.

Post-colonial upbringing

Over the decades, Yasmeen Lari has won many awards and much recognition as an architect, social justice advocate, environmentalist and feminist. While it mayseem like an unlikely path for a girl who was born into a well-to-do family in 1941, she had an unconventional upbringing. Her father, Zafarul Ahsan, was a progressive civil service officer working on development projects in Lahore and elsewhere. Her mother, Nabiun Nisa, valued education and took pride in her role as a bureaucrat’s wife who could ride a horse and entertain guests with equal aplomb.

Zafarul treated his three daughters no differently from their brother, and Nabiun encouraged them to do well in school. Lari became especially aware of politics and poverty after Partition in 1947, when Britain ended its rule of India and carved off a portion to create Pakistan.

Dividing the subcontinent into Hindu-majority India and Muslim-majority Pakistan resulted in the displacement of millions of people. Zafarul was made deputy commissioner of Lahore, which included overseeing refugee camps and creating residential areas. At home, he would talk about bereaved people, impoverished women selling sweets to the rich and the desperate need for housing.

“I understood for the first time that there can be adversity, and that people needed help,” says Lari. “My sisters and I were the first post-colonial generation. Many women had played important roles in the struggle for independence. It followed that women should participate in nation-building.”

An education

Listening to her father talk about the housing crisis and need for architects made an impression on Lari. On a family visit to London when she was 15, she applied to the school of architecture at Oxford Brookes University. She laughs as she recalls her boldness. “I was too young, and I didn’t have a portfolio of sketches or drawings, so they told me to learn to draw and then come back.”

After two years of daytime and evening classes, Lari was admitted to the architecture program as one of only five women in a class of more than 30.

Protected by her family and her husband, Suhail Zaheer Lari (who passed away in 2020), Yasmeen Lari experienced little sexism or prejudice in England. Even Karachi, where she started working after returning to Pakistan in 1964, was progressive. Building-site contractors might test her mettle by making her climb wobbly ladders in her sari, but her married status and privileged background kept her mostly insulated from discrimination.

Lari gained inspiration by exploring the historic areas of Pakistan. In Kashmir and Sindh she admired the flood-resistant heritage buildings made with local materials to withstand extreme weather. And she loved the winding streets and beautiful terraces in Lahore and Multan. As architect for a Lahore social housing project in 1973, Lari listened to the local women and ensured that there were safe, open spaces to raise children and chickens alike.

Big time

Yet soon she heard the siren call of commercial projects, with their creative freedom, large budgets and luxurious materials. From 1980 to 2000, as her buildings rose across Karachi, including the Taj Mahal Hotel (now the Regent Plaza), the Finance and Trade Centre, the Pakistan State Oil House and the ABN AMRO Bank, Lari’s renown grew. She held senior positions in national and international architectural groups, was a member of governmental advisory councils and was a keynote speaker at conferences. “It was a very heady feeling,” she says.

Despite her success, she found ways to stay grounded. Lari and her husband, a historian, created the non-profit Heritage Foundation of Pakistan to celebrate and conserve the country’s historic architecture, art and culture. Lari wrote papers and books on these themes and helped save several prominent buildings.

But it wasn’t enough to offset her growing discomfort with corporate projects. In 2000, the thrill of winning big projects was gone, and Lari retired.

“I realized I was just working with rich people,” she says. She could no longer justify fashioning buildings out of unsustainable materials like polished granite and mirrored glass when corruption was rising and millions lived in poverty, with limited access to housing, sanitation and water.

“Perhaps with my present work, I am atoning,” says Lari.

Sustainable visions

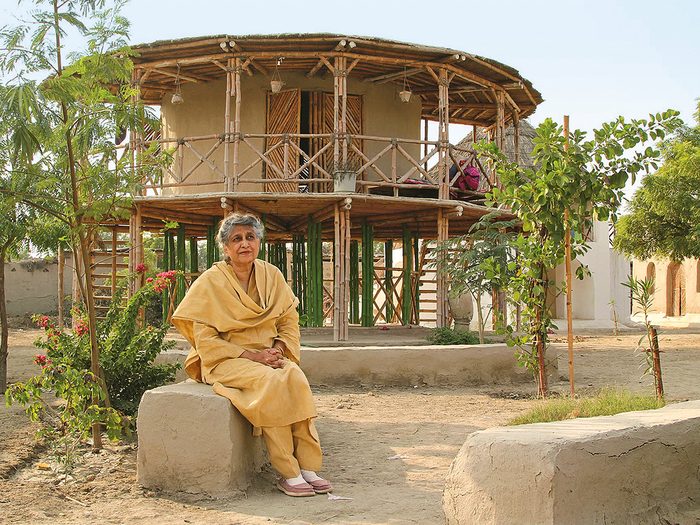

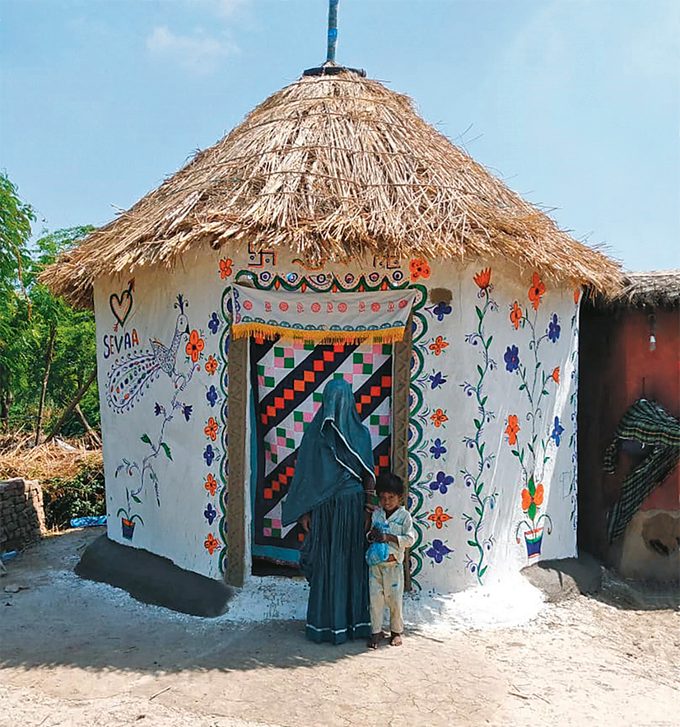

In 2013, Lari was giving a tour of a village in the southern province of Sindh that had been rebuilt after monsoon floods so destructive they impacted some 20 million Pakistanis. In a crisp white kameez and printed headscarf that fluttered in the breeze, she watched as villagers showed off the buildings she had designed. “Our old buildings used to leak when it rained, but these stay dry inside,” one villager told Lari.

The new bamboo structures are covered in a mix of sand and lime called limecrete, which holds up well in Pakistan’s climate. And women can beautify their new homes by painting designs on them, an aspect Lari loves.

Pakistan’s location and melting glaciers place it within the top 10 countries most impacted by climate change over the past two decades, even though the country itself emits less than one percent of global greenhouse gases. Ironically, rebuilding projects funded by government and non-governmental organizations tend to use concrete, burnt brick, metal sheets and other expensive, non-local building supplies.

Lari points out that the creation and transport of these materials contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions, with concrete being one of the worst offenders. Furthermore, they don’t perform well in severe weather.

In contrast, Lari’s shelters, inspired by traditional designs and made with sustainable materials such as reed matting, bamboo, mud and lime that are sourced locally first, can better withstand disasters. Bamboo homes on stilts allow water to flow through, while cross-bracing provides strength and flexibility during earthquakes. Lari’s insistence on low-cost, zero-waste and zero-carbon buildings reflects her commitment to the planet.

Trust local traditions

While her passion for sustainability has grown over the years, her faith in traditional relief funding and charity models has withered. Over two decades she has learned that the approach typically used by government and non-governmental organizations alike doesn’t work well. Locals are often treated like helpless victims, and megaprojects are developed using outside labour. Also, funds are often siphoned away via administrative fees.

“I have seen too much mismanagement when intermediaries are involved,” says Lari, who favours working at the community level. “These are the people who need me.”

Lari calls this local, cost-effective, participatory and zero-carbon approach “barefoot social architecture,” which is helping to create an ecosystem of “barefoot entrepreneurs.” For example, she has created a program that teaches impoverished people in Sindh province to construct buildings and to create and sell mud bricks, bamboo panels, terracotta tiles and other building materials.

Anyone can learn by watching DIY videos on Lari’s Zero Carbon Channel on YouTube. Also, workshops led by local experts and artisans are held at a training centre in Pono Markaz and at the beautiful, airy Zero Carbon Cultural Centre in Makli. Built by locals and Lari’s Heritage Foundation of Pakistan, the latter is the biggest bamboo structure in the country.

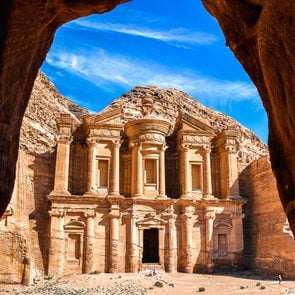

The town of Makli is located about 100 kilometres east of Karachi. Almost half the people in the region live in poverty, and many beg at the nearby Makli Necropolis, a UNESCO World Heritage Site with its nearly half a million tombs and graves. A day’s worth of alms might be 100 Pakistani rupees—equivalent to 50 cents and not enough to feed a family. When locals learn to create and sell tiles, organic soap and other products at the Zero Carbon Cultural Centre, however, they make at least four times that much. Skilled workers share their knowledge, creating more prosperity.

Women and youth gather at the centre to socialize and learn. “The women are uppermost in my mind,” says Lari. “They are the ones who really suffer.”

Household solutions

This feminist inspiration has fuelled many of Lari’s designs, which now include household innovations. For instance, more than 80,000 of her limecrete and smokeless cookstoves, called Pakistan Chulahs, have been built and decorated by villagers.

The device, which won a UN World Habitat Prize in 2018, costs about $10 to make and is fuelled with agricultural waste. The stoves stand higher than flood levels, making them safer than smoky, open cooking fires on the ground; they literally and figuratively lift women up.

Another one of Lari’s designs that benefits both women and the environment is a composting private eco-toilet shelter. About 10 percent of Pakistanis lack a toilet or latrine and must seek privacy outside, either far from their residence or at night. The eco-toilet provides better sanitation and hygiene, and more dignity.

Lari’s Holistic Villages project builds on all these advances to help villages become self-sufficient. At a cost of about $200 per household, villagers can build disaster-resilient bamboo houses, Chulah stoves and shared eco-toilets. They have access to solar-powered lights, hand-powered water pumps, instructions and assistance to produce their own food, and training to create income-generating products or businesses.

Lari says about 60,000 zero-carbon holistic houses have been built since 2010. Next, she wants to scale up—and rehabilitate one million households.

In 2022, floods struck again, as glacial meltwater and epic monsoon rains covered one-third of Pakistan, destroying crops, homes and villages. They displaced about 33 million people, many of them already below the poverty line. Lari and the Heritage Foundation organized artisans to create and supply another of her innovations: prefabricated bamboo walls for 3.5-by-3.5-metre quick-assembly shelters.

Creating connections

Lari now travels regularly from her base in Karachi to Makli, to events around the globe and to the United Kingdom, where she holds a visiting professorship at Cambridge University’s department of architecture. For the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, earlier this year she created three stunning bamboo mosques that can be dismantled and reassembled. In 2020 she won the Jane Drew prize for raising the profile of women architects and, in 2023, the coveted Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) Gold Medal. Even King Charles is a fan; one of her shelters can be found on his Highgrove estate.

Lari insists that anyone who wants to help the impoverished and flood-affected in Pakistan should go directly to the people. She recommends connecting with village leaders to help fund things like water pumps, solar panels and school computers. (The Heritage Foundation of Pakistan offers information about villages in need and how to direct donations.)

“It’s no longer a matter of just giving money and cleaning your conscience—you need to create connections,” says Lari. “We need to believe in people’s capacity to bring about change. I treat displaced people as partners, not victims. They know what to do.”

At age 83, Yasmeen Lari is still fizzing with ideas about zero-carbon designs, flood mitigation, skills building and self-sustaining villages. As she said when she accepted the RIBA medal, the honour “has strengthened my mission.”

Many young architects have told her that they find her work inspiring, which gratifies her. “Architects can no longer work for just the one percent,” she says. “That doesn’t allow them to serve humanity as much as they could.”

If you enjoyed this story, read about a website that channels aid directly to displaced Afghans next.