Mysterious Symptoms: Intense Heartache and a Sore Behind

Patient: Marvin, a 55-year-old chemical engineer

Doctor: Dr. Brian Goldman, a Toronto ER physician, CBC host and author of The Secret Language of Doctors

One recent winter afternoon, a middle-aged man walked into the emergency room at a hospital in downtown Toronto, holding his head. Marvin had experienced headaches, but nothing like this. The pain came on gradually, then grew more intense over several hours until it throbbed across his forehead. He also felt fluish and kept rubbing his left buttock. “Aches and pains,” he told Dr. Brian Goldman, who was on call that day. “Must be getting old.” Marvin had no fever, and no one around him was sick.

“I’m an emergency physician, so I always think worst-case scenario,” Goldman says. “This was not a headache guy, so that factor made his case unusual.” Because of the intensity and atypical nature of the pain in his patient, the doctor immediately wondered whether he had a tumour or subarachnoid hemorrhage (a brain bleed often caused by an aneurysm). The other possibility was meningitis.

Goldman started with a physical exam. Marvin’s heart rate was a little elevated. His ears, nose and throat showed no signs of flu or viral infection. “I checked his neck for stiffness, which is a sign of meningitis, but it was normal,” Goldman says.

The only definitive test for meningitis is a lumbar puncture to look for white blood cells in the spinal fluid. But in a patient with intracranial pressure due to bleed or a tumour, the procedure would direct that pressure downward, squeezing the brain toward the base of the skull. “He would lose consciousness, go into a coma and eventually stop breathing,” Goldman says. The doctor ordered an emergency CT scan, which showed that all was well in Marvin’s brain, making it safe to proceed with a lumbar puncture.

Goldman carefully inserted a long needle in the middle of Marvin’s back, between the fourth and fifth vertebrae. The fluid went to the lab, which confirmed the absence of red blood cells, helping the doctor rule out a hemorrhage. However, there were white blood cells-a clear sign of infection. The test showed 95 white blood cells pure cubic millimeter-not a lot, but enough to reveal that Marvin did have meningitis.

The illness, an inflammation of the membranes around the brain and spinal cord, comes in several forms, including bacterial and viral. “Bacterial meningitis is rapidly progressive and often kills young adults,” says Goldman. The viral form has subtler symptoms and is also less likely to be fatal-but it’s most common in kids under five. “I had no idea why he had viral meningitis,” Goldman says. “Then I remembered his bottom.” The doctor asked to take a look.

There, on Marvin’s left buttock, was a red rash with groups of blisters. “The medical mind looks for the connection,” Goldman says. “It doesn’t assume there are two different illnesses.” Suddenly the viral meningitis made sense. In addition to a horrible headache, Marvin had shingles.

The illness is caused by the varicella zoster virus, one in a group of enteroviruses that tend to circulate in summer and early fall. Others include mums and West Nile-and all of them can cause meningitis. Goldman says it’s not uncommon for varicella zoster to lead to shingles, but he’d never seen shingles and viral meningitis occurring simultaneously.

Marvin was admitted and put on acyclovir-the only intravenous antiviral drug that treats meningitis. Two days later, the headache was gone and he made a full recovery. The moral of the story, Goldman says, is to look for a connection. “You never know what you’re going to find.”

Mysterious Symptoms: Chest Pain, Fever and Fatigue

Patient: Angeline, a 32-year-old administrative assistant

Doctor: Dr. Anne McCarthy, chair of the Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel and professor of medicine at the University of Ottawa

In 2013, Angeline visited her doctor. She’d had a fever for several days, her chest felt tight, and she was exhausted. The physician noticed that her lymph nodes were swollen and that she’d lost some weight. He decided to refer her to the Ottawa Hospital for a CT scan and biopsy, which led to a diagnosis of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

The fifth most commonly diagnosed cancer in Canadian adults, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma has a good prognosis when it’s caught early-especially if the patient is under 60. Angeline was given medication to support her immune system, chemotherapy to target the cancer cells and steroids to bolster the treatment. A week later, she became tired and nauseous, and her blood-cell count dropped dramatically. These can be side effects of chemo, but in this case, they were unusually pronounced.

Within days, Angeline’s fever spiked and she had trouble breathing. Bacteria had entered her bloodstream, and she’d developed an infection in her lungs and abdomen. The patient was admitted to the ICU and given antibiotics, but the drugs didn’t help. Instead, Angeline’s breathing worsened, and she was put on a ventilator.

That’s when Dr. Anne McCarthy was called in. The infection disease specialist found traces of a rash on Angeline’s abdomen. When she learned the patient had grown up in Haiti and immigrated to Canada eight years earlier, McCarthy immediately thought of strongyloides.

Strongyloides are a type of roundworm common in Southeast Asia, South Africa and the Caribbean. The larvae are small-about the size of a mustard seed-and are transmitted to humans through contaminated soil. They can penetrate unbroken skin (often through bare feet) and migrate through the body to the small intestine, where they lay eggs.

In this case, the wavy rash on Angeline’s stomach was a clue: it can appear in patients with strongyloides. When McCarthy checked the patient’s stool sample, she says, “the larvae were everywhere.”

Because there are no obvious symptoms, people can be infected for years without knowing they have the parasite. Angeline had experienced mild gastrointestinal issues at times, but otherwise wealthy, apart from her recent cancer diagnosis-until she was given some steroids as part of her treatment. “Strongyloidiasis is a sleeping disease,” McCarthy says. “It can exist in your body and do relatively little harm until you give it an advantage.” Doctors aren’t entirely sure why, but steroids stimulate the parasite to reproduce faster.

Those drugs had indeed unleashed the bug throughout Angeline’s body, a condition known as disseminated strongyloides, which causes death in 50 to 90 per cent of cases. Unfortunately, it takes time to get treatment because the two anti-parasite drugs that fight the disease (albendazole and ivermectin) aren’t licensed in this country, though they are used in the United States. McCarthy had to request permission from a special program through Health Canada. Although she remained in the ICU for almost a month, the patient received the drugs and made a full recovery, at which point she was able to resume treatment for the non-Hodgkin’s syndrome.

Like most people, Angeline had no idea she could be at risk for strongyloides. Even physicians often know very little about the parasite. McCarthy, who chairs the advisory committee that’s developing strongyloides guidelines, encourages practitioners to adopt a few key queries into their preventive care routine: Where were you born? Where have you lived? Have you travelled anywhere for six months or longer? “There is treatment for strongyloides and people can survive it,” she says. “We just need to ask the right questions from the beginning.”

Mysterious Symptoms: Hiccups, Headache and Vomiting

Patient: Olivia, a 24-year-old university student

Doctor: Dr. Anthony Traboulsee, a neurologist at UBC Hospital in Vancouver

Three years ago, Olivia began hiccuping-and couldn’t stop. The bouts, which lasted up to an hour, would dissipate for a similar amount of time, then reappear. Her head ached. A couple days later, she started vomiting. A hospital visit resulted in anti-nausea pills, but the queasiness didn’t stop. Because throwing up can signal a brain tumour, her next trip to the ER two days later led to a CT scan (the results were negative), and a lumbar puncture to rule out meningitis.

A couple days after that, Olivia’s vision blurred, and she had trouble getting out of bed. Still stumped, doctors put her on antibiotics in case her problems were the result of an infection, then monitored her in the ICU. By the next morning, the patient couldn’t see and was paralyzed from the neck down.

“She was fully awake and aware and very frightened,” says neurologist Dr. Anthony Traboulsee, who was called in after an MRI revealed evidence of inflammation, swelling and damage along Olivia’s brain stem and spinal cord. The other doctors suspected acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), a brief, intense inflammation in that area, resulting from a bacterial or viral infection. But ADEM is more common in children and is often mistaken for multiple sclerosis (MS)-which is itself often confused with Neuromyelitis Optica (NMO). Traboulsee suspected this last condition was the culprit.

Much like MS, NMO is a relapsing inflammatory disease that occurs when a person’s immune system attacks the cells in their central nervous system. It affects the optic nerves and spinal cord, and sometimes the brain.

The disease is rare-while about 100,000 Canadians have MS, only about 1,000 have NMO, Traboulsee estimates. “It’s more aggressive than MS, like a forest fire raging through the nervous system,” says the doctor. Symptoms can include blindness, weakness or paralysis, spasms, vomiting, hiccups and loss of bladder or bowel control due to spinal cord damage. In Canada, the only lab equipped to do the blood test required to diagnose NMO is in Calgary. It generally takes two weeks to get the results.

Traboulsee sent the patient’s blood to the lab but didn’t wait to hear back. “It’s like when someone is drowning,” he says. Without treatment-ideally within 48 hours after symptoms appear-most NMO sufferers wind up in a nursing home.

The doctor immediately started Olivia on a plasma exchange to target the inflammation. A day or two later, she could see shapes and wiggle her fingers and toes. He added in chemotherapy, and Olivia’s recovery was quick and dramatic. “The plasma exchange removes the sparks, but the chemotherapy puts out the fire by removing the abnormal immune cells that are creating the destructive antibodies in the first place,” Traboulsee explains.

After a week of receiving the combined treatment, Olivia regained her sight and could walk again. She’s now on long-term preventive treatment and takes azathioprine, an immunosuppressant, twice a day. There have been no relapses since the initial attack. (When it’s not treated, NMO has a 100 per cent rate of recurrence.) Olivia was able to finish her degree and hopes to someday get married and start a family.

“Like with any rare illness, the key is early treatment and preventive care so people can lead normal lives,” Traboulsee says. But not every doctor is aware of every rare disease. “Because NMO is frequently misdiagnosed and can be suddenly severe, patients are sometimes written off. We can rescue them and give them their lives back.”

Mysterious Symptoms: Abdominal Pain, Diarrhea and Fever

Patient: Daniel, a 38-year-old firefighter

Doctor: Dr. Emily McDonald, a general internal medicine specialist at McGill University Health Centre in Montreal

While working as an internist at a community hospital just outside Montreal last June, Dr. Emily McDonald was asked to check on a patient in the ER. Daniel had arrived the night before, complaining of a bad stomach ache and diarrhea. “He was a big, strong guy, but he was pale and sweating and holding his abdomen,” McDonald says. “He looked very sick.”

Daniel’s girlfriend was worried it might be food poisoning: they’d had dinner at an oyster bar two nights earlier, and the symptoms had started shortly after that. The patient had a fever of 40 C, and lab work revealed he had reduced kidney function and his platelet level was low. “The results were abnormal for someone with simple gastroenteritis,” McDonald says. “Low platelets can be a sign of a more serious infection.”

McDonald went to find a bed with a heart monitor in an area for more acute cases. She was working with a nurse when Daniel’s girlfriend suddenly appeared. “She told me, ‘I think you need to come right now,'” McDonald says. “We ran back to the ER.” Daniel was struggling to breathe, and his lips had turned blue.

“His oxygen levels had dropped dramatically,” McDonald says. The doctor put him on a ventilator, but that didn’t help. As a chest X-ray revealed, his lungs were full of fluid. “I called the main academic hospital in Montreal and said, ‘I’m bringing someone in-and there better be a bed when we get there because he’s dying.'” McDonald joined the patient in the ambulance for the 20-minute ride. “By then his oxygen level was life-threateningly low, putting huge stress on his heart.”

For the next three hours, the intensive care team at the hospital worked to stabilize Daniel and figure out what was wrong. The patient was given extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), which involved pumping his blood through a bypass machine to remove carbon dioxide and add oxygen. Meanwhile, an infectious disease specialist tried to determine what Daniel might have been exposed to. His girlfriend mentioned that four weeks earlier, the couple had gone on a camping trip and rented a cabin near Calgary. The specialist asked if they’d seen any signs of mice. They had. She immediately sent Daniel’s blood to a lab to test for hantavirus.

Hantavirus is an infection that can spread to humans if they breathe air infected with the virus, which is shed in rodent urine and droppings. Mice in Quebec don’t carry the virus, but mice in Alberta do. “Some infections are geographically restricted, like malaria in African mosquitoes,” McDonald says. The incubation period is one to four weeks, which coincided with Daniel’s camping trip, and his flu-like symptoms and breathing problems were endemic to the disease. When hantaviruses are inhaled, they invade the tiny capillaries in the lungs, causing them to leak. Eventually the lungs fill with fluid and make it impossible to breathe.

“There’s no treatment for hantavirus except to attempt to support the body,” McDonald says. The virus kills at least 30 per cent of the people it infects. Fortunately, Daniel was put on the bypass machine in enough time to help see him through. After four days, his heart and lungs were able to work on their own. Three weeks later, he was discharged-and his positive results for hantavirus arrived the following day. “It’s not a common test, and it takes a while to run it, so we didn’t know he had the disease until after he went home,” McDonald says. Though his heart had been at a standstill for five days, Daniel emerged from his ordeal with no neurological damage. Today, he’s back fighting fires.

Mysterious Symptoms: Numbness in One Leg, Abdominal Pain and Inflammation in a Toe

Patient: Tara, a 34-year-old sales representative

Doctor: Dr. Heather Cox, a surgeon at the Northern Alberta Vascular Surgery Centre in Edmonton

In March 2015, Tara visited the walk-in clinic in her small town in northern Alberta. Her right middle toe had been red and swollen for a week, and now she was worried because her right leg and foot felt numb. The doctor there diagnosed her with a general infection and prescribed an eight-week course of antibiotics. Tara’s sore toe improved, but the numbness didn’t. That sensation evolved into pain that increased over the next three months, making walking difficult. She also had sporadic bouts of stabbing abdominal pain for several seconds at a time.

After nearly four months, pain and numbness left Tara so debilitated that she went to the ER three times in one week. On her third visit, an ultrasound revealed that she’d lost all function in a kidney, but one physician wasn’t convinced that this was the only problem.

When a kidney fails, most people experience back pain, but Tara’s discomfort was at the front of her abdomen. The doctor consulted the Grey Nuns Community Hospital in Edmonton, where Dr. Heather Cox was on call. “He couldn’t find a pulse in her foot, her toes were blue, and she had no feeling in her leg,” recalls Cox, who told him to send the patient over immediately.

Tara arrived at the hospital at midnight. Cox ordered a CT angiogram (a CT scan that reveals the veins and arteries). The doctor was dismayed by what she saw. “The vessel going to the dead kidney was completely blocked, as was the one supplying her right leg, from her belly button to her ankle,” she says. There were blockages on the left, too. Cox discovered the source of the patient’s abdominal pain: two of the three arteries leading to her gut were obstructed or damaged.

Tara had vasculitis, a recurring inflammation and scarring of the blood vessels that can cause vein and artery walls to become so thick that they close. It’s a rare condition with a mortality rate of about 10 per cent, Cox says.

The solution was to bypass those scarred channels. The procedure helps, but vasculitis has a high rate of recurrence. A rheumatologist started the patient on steroids to reduce inflammation and a vasodilator to open her arteries and capillaries. Two days later, Cox attached an artificial blood vessel to the healthiest ones she could find in Tara’s legs, bypassing more damaged sections.

The surgery lasted five hours. When Tara woke up, the pain was gone. She still had numbness in her third toe (the redness mistaken for an infection had actually been early gangrene, though circulation was restored after surgery), but she could feel her leg again. She was able to walk within 10 days. Because the vessels to her gut were so damaged, however, she still had trouble eating-a condition that will likely continue for the rest of her life.

After a month, Tara returned home. But as she was weaned off the steroids, the numbness returned to her right leg. Back at the hospital in Edmonton, a CT scan determined that the inflammation had returned and the bypass was blocked.

Although Cox offered her another reconstruction, the patient was concerned about the risks of infection and digestive issues-invasive procedures could make her existing problems worse. “Surgery can have a paralyzing effect on the gut as the body focuses on healing elsewhere,” the doctor says. Tara was also dismayed at the idea of undergoing another operation that might not save her leg in the long run.

Instead, she opted to have her leg amputated below the knee. Since Tara is young, she’s a good candidate for a prosthetic. She’ll need to remain on steroids and blood pressure medication permanently to keep her vessels open and blood flowing to her organs. “It had been such a long ordeal, and she just wanted to get on with her life,” Cox says. “It was a difficult decision, but she handled it incredibly bravely.”

Mysterious Symptoms: Persistent Cough and Night Sweats

Patient: Dr. Beth Donaldson, medical director of Copeman Health Care in Vancouver

Doctor: Dr. Khaled Ramadan, a hematologist at Providence Health Care in Vancouver

In late 2009, six months after giving birth to her son Oscar, Dr. Beth Donaldson, then 34, suddenly developed a deep, forceful cough. When it hadn’t resolved itself after a few weeks, she visited her family doctor, who prescribed antibiotics. A month later, she was still coughing. Her GP figured she had post-viral bronchitis and put her on a puffer.

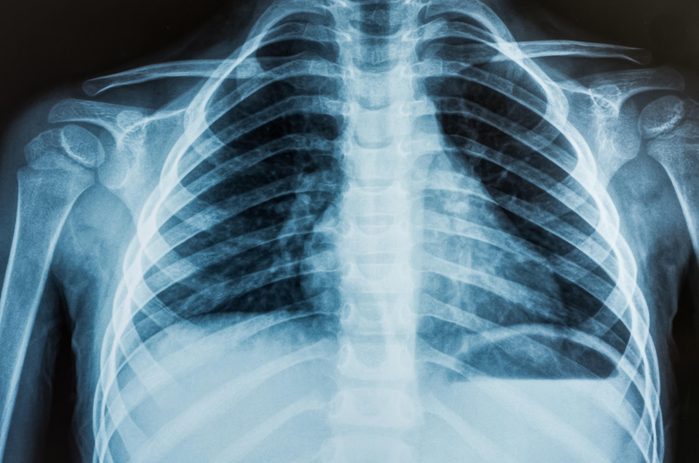

It didn’t help. In fact, Donaldson’s fits became so violent that she fractured four ribs. Her doctor X-rayed her chest and suggested she take drugstore painkillers. Every cough was excruciating. After about a month, Donaldson began waking up in the night, itchy and drenched in sweat. “I was breastfeeding and thought it was because I was hormonal,” she says. She observed that the veins on her neck were dilated. “I dismissed that, too. I was so hot, I decided that must be the reason.” After several sleepless weeks, Donaldson’s mother finally urged her to see the doctor again.

A second chest X-ray, broader and less targeted than the first, revealed a large mass just under the left side of Donaldson’s rib cage that was compressing her lungs, causing the cough and threatening to cut off her airway. She was told it could be one of four things: lung cancer, thymoma (a rare cancer of the lymphatic system), Hodgkin’s lymphoma or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (the distinction depends on abnormal bodies called Reed-Sternberg cells. If they’re present, it’s classified as Hodgkin’s). Dr. Khaled Ramadan was called in to oversee the biopsy. “Her disease was quite advanced,” he says. “It was urgent that we start treatment to shrink the mass and reduce the risk of airway obstruction.”

The biopsy revealed that Donaldson had Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a variety that occurs in only about 2.7 out of every 100,000 people. “Although lymphoma is a common cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma represents approximately 10 per cent of all cases,” says Ramadan. Many types of lymphoma have grave prognoses, but fortunately, the Hodgkin’s form is treatable, with cure rates of around 90 per cent.

Five days after her diagnosis, Donaldson started chemotherapy, going once every two weeks for six months. She wanted more children and worried that the treatment might affect her fertility, but Ramadan assured her that the chemotherapy she was receiving doesn’t usually damage the ova. Besides, the disease had gone for so long without a diagnosis that waiting wasn’t an option.

While the symptoms Donaldson experienced are common indicators of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, patients and doctors often overlook them. “Unfortunately, the diagnosis is delayed in many patients because the signs are so non-specific,” says Ramadan. “If you develop unintentional weight loss, heavy night sweats or fevers in the absence of infection, it’s important to bring that to a doctor’s attention.”

After a single round of chemo, the mass in Donaldson’s chest started to shrink. Once she’d had six treatments, it was no longer detectable on a positron emission tomography (PET) scan, which uses a radioactive tracer to look for disease in the body. Her cough was finally gone, too.

“They told me if I’d waited another two weeks, the cancer could have cut off my jugular,” she says. “Let’s just say I order a lot more chest X-rays for my own patients now than I used to.” After her treatment concluded and she got the go-ahead from her doctor, Donaldson had no trouble getting pregnant with her second son, Angus. Six years after her diagnosis, she’s still healthy and cancer-free.

Mysterious Symptoms: Diarrhea, Exhaustion and Jaundice

Patient: Daniel, a 42-year-old communications manager

Doctor: Dr. Les Lilly, medical director of liver transplants at Toronto General Hospital

Last April, Daniel got sick while travelling in India. He’d been careful to drink only bottled water. He loved street food, though, and, in the second week of his trip, developed severe diarrhea. A doctor at a clinic near his hotel in New Delhi prescribed an antibiotic, which made Daniel feel better. But two weeks later, after he had returned home to Ajax, Ont., and finished his course of medication, the diarrhea resumed.

His GP suspected giardia, an intestinal infection caused by microscopic parasite, and put him on metronidazole, an antibiotic commonly prescribed to treat the condition. A stool-sample test confirmed the infection, but even after Daniel’s gastrointestinal symptoms abated, something wasn’t right. He felt increasingly tired. Three weeks later, his skin started turning yellow.

Doctors at a local hospital couldn’t determine the source of Daniel’s jaundice. He had no history of liver disease and had been vaccinated against hepatitis A and B, as well as yellow fever, typhoid and Japanese encephalitis, all of which can interfere with liver function. An ultrasound showed no abnormalities in his blood vessels or bile ducts. He was screened for hepatitis B and C, Epstein-Barr (a virus that causes mononucleosis, which can lead to liver problems) and cytomegalovirus (a common virus that can attack the liver), but the results were negative.

Still, Daniel’s liver biochemistry was abnormal, and tests showed his clotting factors were off. The organ makes proteins that help blood clot; people with acute liver failure often develop internal bleeding, especially in the gastrointestinal tract.

A liver biopsy suggested that Daniel had a viral form of hepatitis. After five days, his health was declining, and he was transferred to Toronto General Hospital. “He was very jaundiced by this time,” says Dr. Les Lilly, the hospital’s liver transplant specialist. Two days later, Daniel became confused and no longer knew who he was. That’s when his name was added to the transplant waiting list, where patients are given priority based on both the severity of their disease and the availability of a suitable donor.

“We couldn’t be certain what was causing his liver failure,” Lilly says. Even the antibiotic Daniel had taken in India could’ve been to blame. “An accurate drug history is important because almost any medication can cause liver problems.” Given the patient’s travel history, Lilly suspected hepatitis E, a water-borne virus that’s rare in North America but endemic to South Asia. (A blood test confirmed the diagnosis, but results wouldn’t arrive for two weeks.)

There is no vaccine or drug to treat hepatitis E, although the illness is typically benign, Lilly says. “You might feel unwell for a few days and probably turn a little yellow, but by the time you decide to do something about it, you start feeling better. This patient had an unusually severe reaction.” Daniel’s gastrointestinal issues were likely caused by a combination of giardia and hep E-diarrhea commonly occurs in people with advanced liver disease.

Within days, a donor in another province became available, and doctors began prepping the patient for surgery. While they waited for the liver to arrive, Daniel’s confusion cleared. In a matter of hours, the transplant was cancelled. Over the next few days, his liver biochemistry started returning to normal. Two weeks later (about two and a half months after his trip to India), he was discharged, although it took six months for a full recovery.

Daniel was lucky. By the time liver failure reaches the stage where the patient becomes confused, there’s only a 15 per cent chance that the organ will recover on its own and the patient won’t require a transplant. But when viral hepatitis is caught in time, “if you can support the patient through the worst of it, the liver will repair itself,” Lilly says. “It’s a remarkable organ.”

Mysterious Symptoms: A Non-Stop Runny Nose

Patient: Jia, a 39-year-old defence attorney

Doctor: Dr. Satish Govindaraj, an ear, nose and throat specialist at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City

Jia was at her office working one afternoon in May 2014 when her nose suddenly started running. At first she thought it was just a cold, or maybe seasonal allergies, but the fluid seemed to be coming from only her left nostril-and it wouldn’t stop. Worse, whenever she bent down or exerted herself in any way, the flow increased significantly.

After four days, she went to her family doctor, who told her the symptoms weren’t typical of a sinus infection: she didn’t have a headache, cough or sinus pressure, and the fluid was clear, as opposed to yellow or green. Still, he prescribed an antibiotic and a corticosteroid nasal spray, just in case. Two weeks later, Jia’s nose was still running. She had no history of allergies and was otherwise symptom-free, so her doctor ordered a CT scan.

The radiologists didn’t highlight anything out of the ordinary in the results, but Jia’s GP was concerned she might have a cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak. He referred her to Dr. Satish Govindaraj, who confirmed those suspicions. The CT had actually revealed a small bone gap in Jia’s skull, and brain fluid was leaking from her nose.

The patient was fortunate that her physician picked up on the symptoms, says Govindaraj, who took on Jia’s case after the leak was confirmed. In cases of runny noses caused by colds or allergies, mucus is usually present in both nostrils and at some point decreases (or even disappears). In contrast, “because CSF fluid is continuously produced,” he says, “it’s usually more of a steady drip.”

Jia had a spontaneous leak, meaning she had no preceding trauma that might have caused it. The condition is rare and, though it tends to occur most often in obese or overweight middle-aged women (weight around the abdomen puts pressure on the veins, and that pressure is transmitted to the brain), Jia didn’t fit the profile. However, the CT scan indicated that the lining of her brain had herniated into her sinus cavity. A tiny tear had developed in the lining, leaking fluid from her brain into her nose.

A sample of the fluid confirmed the presence of beta-2 transferrin, a protein found only in the eyes, liver and brain fluid. “If you encounter it coming out of the nose, you know it’s from the brain,” Govindaraj says.

Without surgery to repair the leak, Jia was at risk of meningitis or a brain abscess-infection could be easily passed from her nose to the vulnerable tissue poking into her sinus area.

After a second CT scan to guide the procedure, Govindaraj performed endoscopic surgery through her nostrils. He removed the exposed area of brain, patched the gap in her skull with bone and tissue from her nose, bolstered the graft with dissolvable packing and inserted a sponge to keep pressure on the area. “Because the patient had such a high-flow leak, we had to get it sealed fast.”

Five days after the surgery, Jia returned to Govindaraj’s office to have the sponge removed. While the leak is fixed, there’s still a risk a new one could develop. Govindaraj prescribed acetazolamide, a diuretic that also decreases brain-fluid pressure, and recommended a neuro-ophthalmologist to monitor her for signs of elevated intracranial pressure in her eyes.

The doctors still don’t know why Jia-or anyone else-experiences unusually high brain-fluid pressure. In her case, accumulated stress on her skull over time led to the gap, which may have already been there for months or years before the leak occurred. “I still see her once a year, just to check that she’s doing well,” Govindaraj says. “But she’s back to regular activity with no restrictions and is living a normal life.”

Mysterious Symptoms: Extreme Back Pain and Unexplained Weight Loss

Patient: Brett, a 52-year-old factory worker

Doctor: Dr. Herbert Ho Ping Kong, Osler professor of expert medical practice at the University Health Network in Toronto

It all started with a bad back in the fall of 2014. At first, Brett dismissed it as a side effect of his physically demanding job in an auto plant. But two weeks later, when the pain got worse, he went to his family doctor in Brampton, Ont., who sent him to a physician at the Workplace Safety and Insurance Board (WSIB). The MD there confirmed Brett’s suspicions-he was getting older and doing too much heavy lifting. He was told to rest and take painkillers.

But then Brett began losing weight, and his back pain got worse. A different GP referred him to an orthopaedic surgeon. X-rays revealed nothing amiss, so Brett was sent home with more meds. By now it had been three months, and the pain was so intense he could no longer work. He tried a third GP, who discovered blood in Brett’s urine and referred him to a nephrologist. Concerned he might have a tumour, the doctor called for a cystoscopy (in which a camera is inserted through the urethra to the bladder to look for signs of cancer), but the results were negative.

Brett did, however, test positive for IgA, a relatively benign disease that occurs when the antibody immunoglobulin A lodges in the kidneys, causing inflammation and, in some cases, resulting in blood in the urine. The doctor told Brett to manage his blood pressure and cut back on cholesterol, which would help protect his kidneys and slow the progression of the disease, which can’t be cured.

But IgA didn’t explain the back pain. At this point, six months into his ordeal, Brett could hardly walk. He’d also begun sweating profusely and had lost 30 pounds. Then one of his fingers turned black. He consulted a fourth GP, who sent him to Toronto Western Hospital to see Dr. Herbert Ho Ping Kong, who’s renowned in the city for his skill in sorting out difficult diagnoses.

“If only someone had listened to his heart,” says Ho Ping Kong. Within two minutes, the doctor was able to diagnose Brett with subacute endocarditis. “He would’ve been dead within three weeks,” says Ho Ping Kong, who sees a case like this every couple of years; it’s estimated that between two and six of every 100,000 people suffer from the condition. Endocarditis is an infection of the inner lining of the heart that affects individuals who have diseased or damaged cardiac valves, such as those born with a congenital defect. (The doctor suspects Brett may have had rheumatic heart disease.) Bacteria in the bloodstream travel to the heart and attach themselves to the damaged area, causing symptoms that include severe muscle pain, sweating, weight loss and blood in the urine.

Given the patient’s history and symptoms, Ho Ping Kong knew as soon as he heard a heart murmur that it was endocarditis-and that they had to move fast. The blackened finger was a sign of a septic embolism: infected tissue had broken off the heart valve and lodged in the artery in his finger. “It was an emergency,” says Ho Ping Kong. “More pieces could break off and travel to his legs, his kidneys or his brain and cause a stroke.”

Over the next week, the patient was given antibiotics and had cardiac surgery to replace the valve and prevent heart failure. Because the damage was extensive, he also needed a pacemaker. Although he couldn’t lift as much as he used to, Brett was back at work within two months, pain-free. “There are some cases where the clinical diagnosis is as good as any kind of CT scan or MRI,” Ho Ping Kong says. “It’s that combination of taking a complete medical history and a thorough physical exam-and you always have to listen to the heart.”

Mysterious Symptoms: Headache and Blurry Vision

Patient: Mahika, a 27-year-old dental hygienist in New York City

Doctor: Dr. Raj Shrivastava, a neurosurgeon and associate professor at the Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City.

Mahika wasn’t initially worried when she felt a persistent throbbing behind her eyes two years ago. It was January and she had a bad cold, so she figured the pain was probably due to a sinus infection. She self-medicated with overthe-counter pain medication for a week, and when that didn’t help, she went to her family doctor, who put her on a course of antibiotics.

Over the next two weeks, however, Mahika’s headaches worsened, and her vision grew blurry. Assuming she needed a new prescription for her eyeglasses, she visited her ophthalmologist. Her eyes looked fine, he said, but he couldn’t explain the blurred vision. By now the pain in her head was becoming unbearable: she had trouble concentrating at work and couldn’t read or watch TV.

Mahika returned to her doctor. She’d never had a migraine before, but her mother was prone to them, and her doctor suspected that might be the issue. She referred Mahika to a neurologist, who prescribed triptan drugs, a common migraine treatment that constricts blood vessels and blocks pain pathways in the brain.

Unfortunately, that didn’t work. It had been nearly four months since her headaches began, and Mahika was having trouble seeing out of her left eye. Fearing a brain tumour, the neurologist booked an MRI. The imaging revealed a large skull-base meningioma-a mass that arises from the membranes surrounding the brain and spinal cord. It was pressing on her optic nerve, causing vision loss, and was surrounded by a dense supply of arteries. A neurosurgical colleague said the tumour was inoperable and the only option was radiation, but Mahika’s neurologist wasn’t ready to give up.

She referred the patient to Dr. Raj Shrivastava at Mount Sinai, who’d operated on difficult cases in the past. “The patient was an emotional wreck,” he says. “But when I saw her imaging, I believed the tumour could be operated on endoscopically, by going through her nose with a camera.” According to Shrivastava, the efficacy of radiation is only about 50 per cent at best. Mahika was in danger of losing vision in both eyes, then developing paralysis if the tumour continued to grow and press on her brain.

Over the next six days, Shrivastava met with a team that included surgeons, engineers, radiologists and computer scientists to determine how to tackle the tumour. Using ultrahigh-field 7T MRI imaging, unique to Mount Sinai’s OR protocol, the team created an intricate 3-D map of the patient’s brain. “It allowed us to plan our trajectory,” Shrivastava says. “We performed a virtual surgery to determine what angle we were going to come in at, how much bone to drill, where each artery was, planning each step in exquisite detail.”

On the day of the surgery, there were nine screens in the operating room, monitored by 10 doctors, who were also watching the patient. “It was the first time we’d integrated all these technologies into a case,” Shrivastava says, noting that the complexity of the tumour spurred him to take this novel approach.

After almost 12 hours of surgery, Mahika woke with improved vision. The doctors removed the entire mass, significantly reducing the risk of its return. She spent three days in the hospital and two weeks recovering at home. By then, the headaches were gone and her vision was fully restored. And happily, tests confirmed that the tumour was benign.

“Everything went according to plan,” Shrivastava says. “With the help of technology, neurosurgery is leaving less to improvisation. As for the patient, this had been such an overwhelming experience that she didn’t believe the tumour was actually gone-she was very, very happy.”

Two years later, Mahika is still healthy-and happily tumour-free.

Mysterious Symptoms: Low-Grade Fever, Persistent Cough and Fatigue

Patient: Ted, a public sector worker in his late 40s

Doctor: Dr. Neil Shear, head of dermatology at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto

For three weeks in February, Ted struggled to banish what he thought was a nasty flu bug. He had a dry cough, a fever of 38 C and a feeling of fatigue that eight hours of sleep – and over-the-counter cold medications – couldn’t fix.

Finally fed up with feeling lousy, Ted went to his family doctor, who discovered puzzling sores the size of small warts inside his mouth and nose and referred him to the internal medicine clinic at Sunnybrook Hospital, in midtown Toronto. The physician there suspected vasculitis – inflammation in the veins, and arteries that often presents with fatigue, coughing and skin sores.

It was now April, three months after Ted started feeling sick, and his health quickly deteriorated: his cough worsened and he was so tired he could barely make it through his workday. He’d also lost his typically healthy appetite and was dropping weight. More troubling: the lesions in his mouth and nose were expanding (some to the size of toonies), and had spread to his throat.

Ted was referred to an oral surgeon, who biopsied the lesions in his mouth. The results were read as granulomatous vasculitis, aligning with the internist’s earlier suspicions. This variant typically involves the upper respiratory tract – an X-ray revealed a fuzzy shadow in Ted’s lungs. The disease affects about one in 25,000 people, often in their 40s and 50s, and may lead to heart disease and kidney damage. While the condition can be very serious, when it’s diagnosed and treated promptly, the current survival rate is about 90 per cent.

Unfortunately, two weeks of taking corticosteroids to control inflammation and suppress his immune system didn’t relieve Ted’s symptoms. The lesions had spread to the skin on his arms, legs and torso, and the abscesses in his mouth and throat made it difficult to eat or talk. By this point, it had been almost six months since the onset of his illness, and Ted had lost hope of ever getting better. Because the sores on his body were so disfiguring, he was referred to dermatologist Dr. Neil Shear.

Shear took one look at the patient and knew he didn’t have vasculitis. “Once you see a condition like this, you don’t forget it,” he says. What Shear saw was blastomycosis, an airborne fungal infection that originates from mould that grows in damp soil and decomposing leaves. It’s found in the United States and Canada, as well as parts of India and Africa, and affects people (and animals) who breathe in the spores, though not everyone who’s exposed will develop the infection.

Flu-like symptoms typically appear one to three months after a person inhales the fungus. Once the micro-organisms enter the lungs, they transform into a yeast that spreads through the bloodstream. “Eventually, the patient would have been on a ventilator and likely would have died,” Shear says.

Blastomycosis is uncommon in many regions, and the patient is still unsure where he picked up the illness. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, yearly incidence rates in the U.S. are approximately one to two cases for every 100,000 people. Shear says the infection is often misdiagnosed because it so closely resembles the flu. When reviewing biopsy results, it’s helpful to know what to look for, he says. In Ted’s case, the fungal elements were noted but weren’t perceived as being significant. “It can take a little extra detective work.”

Fortunately, the condition is treatable. Although Shear performed a second biopsy and fungal culture, he didn’t wait for the results to start a regimen. He promptly prescribed a high dose of antifungal medication two times a day for a month. “After a week, the patient started getting better,” Shear says. Today, Ted has fully recovered.

Mysterious Symptoms: Swollen Legs and Shortness of Breath

Patient: Alberto, a 33-year-old lab technician in Chicago

Doctor: Dr. Nir Uriel, director of heart failure, transplant and mechanical circulatory support at the University of Chicago Medicine

Alberto was diagnosed with Crohn’s disease in his early 20s but controlled flare-ups in his digestive tract with a restricted diet and drug therapy. In May 2014, two years after he’d started a regimen of methotrexate, an immune-system suppressor that reduces inflammation, he noticed that his legs looked swollen. He also felt fatigued and started losing weight. The doctor he consulted diagnosed him with cirrhosis – the medication he’d used to treat his condition had cause irrevocable scarring to his liver.

Alberto was prescribed a different anti-inflammatory, which should have resolved his symptoms. But instead, his legs and hands ballooned, and his skin appeared puffy and stretched. He had edema: swelling caused by excess fluid in the body’s tissues. Within seven months of his cirrhosis diagnosis, Alberto was having trouble walking and had developed shortness of breath. His doctor sent him for an echocardiogram at a local hospital, concerned that the latter symptom suggested a heart-related problem.

The test revealed that Alberto had reduced ejection fraction – a measurement of the amount of blood pumped out of the heart each time it contracts. He was diagnosed with acute decompensated heart failure (a sudden worsening of symptoms), but cardiologists couldn’t figure out why. He had no family history of cardiomyopathy (a condition distinguished by abnormalities in the heart muscle); there were no signs of inflammation; and an angiogram showed only healthy looking arteries.

By early 2015, Alberto was wholly debilitated and terribly depressed. As they struggled to identify the source of his heart trouble, cardiologists treated him with a host of medications to treat cardiac failure, but his blood pressure dropped so low that his body couldn’t tolerate the treatment. It was then that Alberto was referred to Dr. Nir Uriel.

“The patient’s parents had to wheel him into the clinic because he didn’t have the strength to make his way from the parking garage,” Uriel says. “He had end-stage heart failure.”

Uriel began evaluating Alberto for a combined heart and liver transplant, while simultaneously trying to determine the cause of his cardiac issues. “Because a lot of tests had already been done, we tried to think outside the box, to find something that hadn’t been done.”

Uriel wondered whether the Crohn’s, which made it difficult for the patient’s body to absorb nutrients, might be at fault. He analyzed Alberto’s blood for minerals crucial to heart health and found a selenium deficiency, something no one at the hospital had encountered before.

“Selenium is responsible for the electrical activity between the cells in the heart. When a patient is deficient, it can cause cardiomyopathy,” Uriel says, adding that it had taken a few months to identify the source of Alberto’s heart trouble because he was in such bad shape. “We really thought, This heart is done.”

After consulting a nutritionist to determine how best to reverse the patient’s deficiency, they put him on a selenium drip. Within days, Alberto’s condition had improved. “Six months later, his heart had completely recovered,” Uriel says, “with no need for a transplant.”

While Uriel acknowledges that this was a rare twist in a cardiac-failure diagnosis, he says the case shows how important it is to think about what might be missing in the blood, especially in a patient with nutrient-absorption issues. After leaving the hospital, Alberto changed medications and followed a specialized diet that includes selenium supplements. Now, two years after his ordeal began, he’s back at work and playing golf again – with a healthy heart.