What is physician-assisted dying?

Canadian lawmakers passed legislation over the summer that legalized doctor-assisted death. The law, Bill C-14, was introduced in April 2016 and later received royal assent. There are two types of Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID) in Canada: the medical practitioner can directly administer a substance that causes the death of the person who has made the request, or the medical practitioner can give his or her patient a substance that they can administer themselves. Here are five things you need to know about the new law.

Physician-assisted dying gives people the right to die with dignity

Simply put: physician-assisted dying is about giving patients who are suffering the right to die with dignity. “We value all lives and also value the choices of people who are able to make a decision on what they consider quality of life,” says Maureen Taylor, co-chair of the Ontario Advisory Panel on Physician-Assisted Dying. Taylor appears in the CBC documentary Road to Mercy, which documents Canada’s first sanctioned physician-assisted deaths. “We have to be careful not to impose our belief systems, cultural biases and sense of self-worth onto others,” she says.

Her late husband, Dr. Donald Low, succumbed to brain cancer in 2013; he was also an advocate for assisted death. “Although I miss him tremendously, I have to accept that he wanted to die with dignity, and what he considered dignity was to not suffer until the very end,” says Taylor.

The law may limit access to certain patients

To qualify for assisted death, individuals must be 18 years and older, have an incurable illness, be eligible for government-funded healthcare, and be in an “advanced state of irreversible decline” where death is imminent. In other words, patients with degenerative diseases like ALS, multiple sclerosis, or Parkinson’s may be denied because their death is not considered foreseeable.

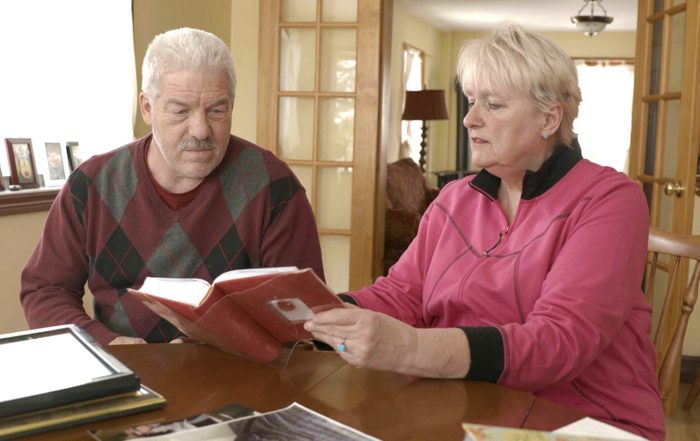

Many Canadians, however, do not have difficulty gaining approval, like John Tuckwell of Edmonton, Alberta, who was diagnosed with ALS in 2012. “The fear of death is something [John] lived with every day,” says Cathy Tuckwell, his sister. “He was afraid he’d choke to death-that the fluids would fill up his lungs and kill him.” Both John and Cathy appear in Road to Mercy. John later succumbed to ALS in his home, opting not to use his court exemption.

Advance requests aren’t allowed

Because individuals with Alzheimer’s will likely lose competence before they reach the law’s required “state of irreversible decline,” they can’t be granted the right to an assisted death that would be carried out at a later time. Currently, there’s no guarantee that patients with conditions like dementia will ever qualify for MAID.

“There have been in cases in Europe where by the time the patient is demented, they aren’t the same person anymore and don’t remember that they’d even made the request in the first place,” says Nadine Pequeneza, a Toronto-based documentary filmmaker and director of Road to Mercy. “Then it becomes a serious ethical dilemma for the doctor.”

Doctors and hospitals can refuse requests

Under Bill C-14, it isn’t mandatory for physicians to assist a patient in dying, nor is it mandatory for institutions to carry out a request. “Access is still a major concern,” says Taylor. “We’ll have to look at the Ontario government ruling for things like, for instance, what happens when a patient makes a request at a hospital that doesn’t provide it.” However, several provincial regulatory authorities encourage doctors unwilling or unable to provide MAID to refer patients to other willing institutions or practitioners.

Individuals with mental illness aren’t eligible

People with mental illness are not eligible for physician-assisted dying if they are suffering only from a mental illness, death is not “reasonably foreseeable,” and said mental illness reduces the individual’s ability to make medical decisions.

“Mental illness is tricky because you don’t see mental illness,” says Pequeneza. “People who are manic-depressive, for instance, or suffering from a personality disorder have highs and lows, so it’s not like a physical illness or degenerative illness where you constantly see someone on a downward slope.”

Road to Mercy premieres on Firsthand on Oct. 6 at 9 p.m. (9:30 p.m. NT) on CBC.