What’s Wrong with Me?

The patient: Kurt* (name has been changed), a 66-year-old living on a pension

The symptoms: Unpredictable episodes of airway swelling

The doctor: Dr. Anette Bygum, dermatologist at Odense University Hospital in Denmark

For Kurt’s entire adult life, he’d been under constant threat of asphyxiation. His first fright occurred at age 20, when his throat suddenly closed up. He’d noticed unusual swelling over the previous couple of years, but nothing this severe. ER doctors suspected an allergic reaction and gave him antihistamines, corticosteroids and adrenaline, to no avail. As a life-saving measure, they surgically opened Kurt’s windpipe with a tracheotomy. Gradually, the swelling subsided.

Kurt went through a similar event a year later. As before, anti-allergy medications had little effect, but this time the swelling, or edema, eventually abated without surgery. Doctors tested Kurt’s level of C1 esterase inhibitor (C1-INH), a protein that blocks fluid build-up in tissues. A genetic condition called hereditary angioedema (HAE) can cause a deficiency of this protein, but it’s rare, affecting only one in about 50,000. As it turns out, Kurt’s C1-INH wasn’t low at all; it was actually elevated, and so another possible answer evaporated.

A Lifelong Struggle

More than 40 years passed, during which time Kurt had multiple emergencies. On one terrifying occasion, he came to the hospital with difficulty speaking, began gasping for air and started turning blue right in front of doctors. That was the day he had his second emergency tracheotomy. He had a third, then a fourth, along with many other hospital stays for edema and milder episodes that he waited out at home. Sometimes, Kurt had to miss family gatherings, and he and his wife were too nervous to travel—what if they couldn’t find a hospital quickly?

Throughout that time, specialists were mystified. One suggested an elimination diet to pinpoint a food allergy, but it didn’t help. They checked his C1-INH levels again, which were still high. Kurt underwent skin-prick allergy tests, but one hopeful reaction—to brewer’s yeast—proved to be a false positive after Kurt was given beer to drink.

These are the signs of oral cancer you should never ignore.

Renewed Hope

In 2014, one of Kurt’s physicians recalled a colleague, Anette Bygum at Odense University Hospital, who had expertise in unusual swellings, and figured a referral was worth a shot. For Bygum, who has done extensive research on HAE, the alarm bells were ringing—especially after she learned that Kurt often had episodes after dental work. Physical trauma and strong emotions can provoke attacks in people with the condition. “I thought his history was so convincing, he should have HAE,” she says.

Bygum suspected, however, that Kurt had a rare subtype called HAE Type II, in which the body makes the C1-INH protein but it doesn’t work properly. Accounting for just 10 to 15 per cent of HAE cases, the subtype was not well-known when Kurt first developed symptoms. Bygum tested Kurt’s C1-INH function and confirmed it was poor. A genetic analysis then solidified the diagnosis by identifying a mutation as the cause.

A Full Recovery

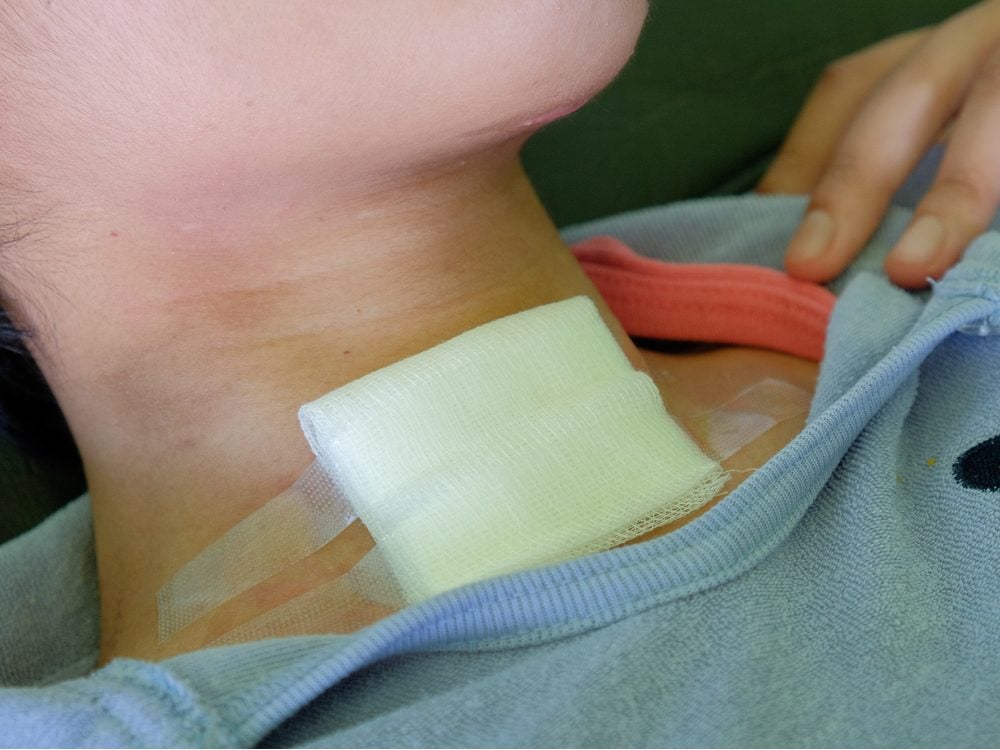

There’s no cure for HAE, but Kurt now carries a vial of C1-INH concentrate. In an emergency, doctors can inject this medication directly or infuse it in an IV drip, instead of performing a tracheotomy.

“He and his wife were very relieved,” says Bygum. Patients with HAE are three to nine times more likely to die from asphyxiation if undiagnosed. And some doctors suggest that scarring from multiple tracheotomies may complicate further procedures.

Ironically, Kurt hasn’t had another crisis in the five years since his condition was discovered. Sometimes, HAE becomes milder with age, says Bygum. But since attacks are triggered by stress, there may be another explanation: “We have often seen attack frequency go down after we tell patients what this disease is. They don’t need to be anxious anymore.”

Next, check out these health symptoms you should never ignore.