The Butterfly Effect

In a stark white examination room at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children (SickKids), a medical team has gathered for a new experimental skin-care procedure. A dermatologist, three residents and a nurse throng Dr. Elena Pope as she applies a translucent membrane to her patient’s raw flesh. The nurse snaps some photos.

“Does it hurt?” asks Pope, the institution’s head of pediatric dermatology.

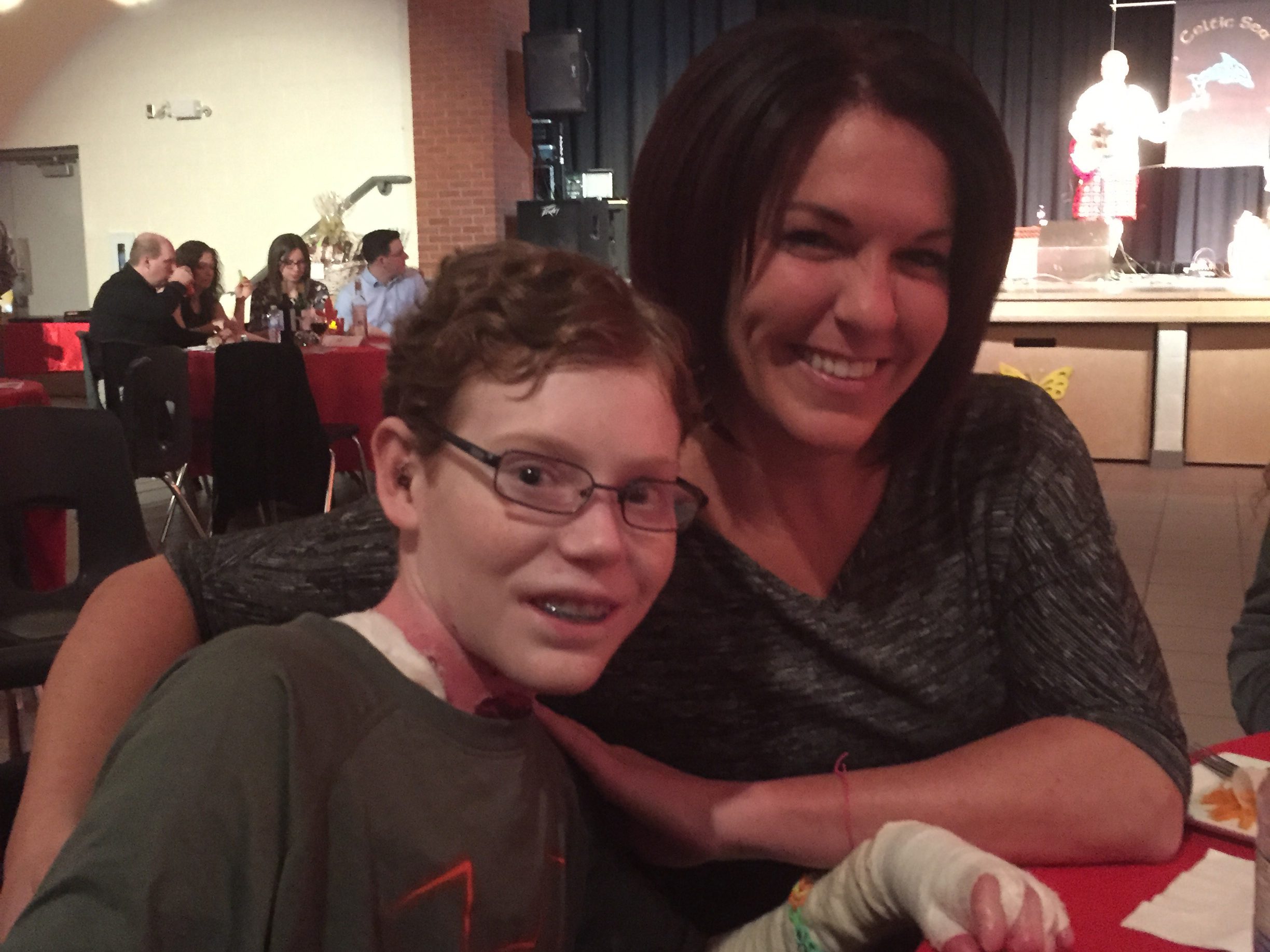

“Just when you touch,” answers 15-year-old Jonathan Pitre before exhaling audibly. Standing at his side with arms crossed, his mom, Tina Boileau, never averts her gaze from her child.

Jonathan is one of about 3,500 Canadians living with epidermolysis bullosa (EB), a genetic condition in which the two layers of skin-the epidermis and dermis-fail to anchor together because they lack one of several key proteins. EB sufferers are nicknamed Butterfly Children, since their skin is as fragile as that creature’s wings-the slightest friction can cause a painful abrasion that won’t heal properly, if at all. Jonathan has the most severe form of the condition; 60 to 70 per cent of his body’s surface is chronic wounds, which can lead to a host of fatal complications. The average life expectancy of someone with his subtype of EB is 25.

On this December morning in 2015, the teen is bound in gauze from neck to waist, and from the thighs down. His exposed skin is a patchwork of red and purple sores. Over the three worst lesions, Pope carefully places strips containing amnion, an anti-inflammatory placental membrane that provides growth factors to promote healing. The hope is that the amnion will help repair Jonathan’s skin and reduce his discomfort; if it works, additional applications can be used to close more of his wounds. The problem is, to test these treatments, Jonathan must submit to the thing that hurts the most: contact.

As Pope continues the treatment, Jonathan whimpers and looks over his shoulder at the group. A bead of sweat clings to his cheek. The doctor asks if he wants a moment.

“You have to do it, so do it,” he says. Above his head hangs a painting of a boy on a unicycle juggling apples. He glances up at it as though seeking advice on how to defy probability.

For people with epidermolysis bullosa (EB), lesions can occur inside as well as outside the body. When Jonathan was born, blistering in his airway impeded his breathing, and doctors were forced to intubate. He spent the next month and a half in the neonatal intensive care unit at the Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario. He was diagnosed with a recessive dystrophic form of the disease, which means both his parents carry the gene. It also means his condition will deteriorate. In the coming years, his compromised body will be at increasing risk of cardiac problems, organ failure and skin cancer. “With EB, every child is different,” says Pope. “He may beat the odds. It’s hard to predict.”

Jonathan weighs 72 pounds-about half the average of a boy his age-and that includes the gains he’s made since a gastrostomy tube was inserted last November, which allows him to receive the nutrients he wasn’t getting orally (eating inflames sores on his gums and in his throat). Chronic scarring has reduced his appendages to stubs, and the buildup of scar tissue has fused his digits and made them appear webbed-a condition called syndactyly. He’s already had three surgeries to separate the contracting fingers from one another. Over the past two years, his compromised mobility has led to osteoporosis, and while he can walk down the hallway at home, he depends on a wheelchair to carry him greater distances.

Ironically, as the disease has become more physically debilitating for Jonathan, it has also been a source of empowerment-for himself and others. In 2012, Pope invited the then-12-year-old to participate in a panel at the Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Association (DEBRA) International Congress, held in Toronto. With typical candour, Jonathan talked about his condition before an audience of nearly 150 that included EB patients and researchers from around the world.

“It was life-changing,” Jonathan says of the experience. “It was the first time I’d ever met someone else with EB. It made me feel like I wasn’t alone anymore.”

Moreover, he realized the effect of his public speaking: “Sharing my story made me feel like I was making a difference. It made me redouble my efforts.”

Since the congress panel, those efforts have included becoming an ambassador for DEBRA Canada. The organization, of which Tina serves as president, has adopted the slogan, “The worst disease you’ve never heard of.” The group is trying to change that.

In October 2014, the Ottawa Citizen-based 30 minutes from Jonathan’s hometown of Russell, Ont.-ran a profile of the teen. Within a matter of days, the story was picked up by other North American outlets and generated more than $100,000 in donations to DEBRA, giving him faith that telling his story might indeed produce results.

Back at their two-storey home in Russell, Jonathan stands hunched on a rug in his mother’s room. Tina sits cross-legged at his feet cutting a strip from a roll of silicone. Jonathan has an angry-looking oval wound on his calf, as though he’s been bitten by a lamprey eel, and when Tina applies the silicone, he gasps sharply. Changing Jonathan’s dressings is an exhausting three- to four-hour process that takes place three evenings a week.

“Ow,” he says. “Ow, ow, ow.” The string of ows turns into an extended, keening howl. Jonathan’s Boston terrier, Gibson, whines from the other side of the closed door.

“Sorry, buddy,” says Tina. As Jonathan’s moan peters out, she prepares the gauze and stretch bandage that will secure the silicone to his leg.

Jonathan turns his attention to sports highlights on the TV. The Ottawa Senators fan has an eye on becoming a sports broadcaster, a career that would suit his confident, unembellished manner. He scoffs at a soccer clip.

“They’re babies,” he says. “Always throwing themselves on the ground, even when they’re just touched.”

Tina asks her son to turn so she can study his backside. Then she removes a needle from its antiseptic sleeve and pops a blister behind his right knee. Jonathan shudders. She can’t always know if an area of skin will be particularly sensitive, and it’s a challenge to be gentle enough. Sometimes when Jonathan lets out a gasp, his mother takes a corresponding deep breath. Then, as he weeps, she busies herself with scissors and silicone, getting a few more strips cut to size.

“I’m hurting him,” Tina says of the dressings ritual. “It’s not quality time.”

But it’s family time nevertheless. At one point, Noémy, Jonathan’s 13-year-old sister, comes in and stretches out on the bed. The curly-haired girl pushes up her glasses and opens a trivia game on her iPhone.

“Whose laws deal with gravity and motion?” she asks.

“Newton,” Jonathan answers.

“How’d you know that?”

Now wrapped to the waist, Jonathan rests on a stool and scrolls through photos of Gibson on his iPhone. Balanced in his lap is a plush wolf named Aurora. “As much as it’s childish, I do what I have to do,” he says. “EB kids like soft things.”

A glistening sore larger than a dinner plate covers most of his back, and Tina begins to tackle it. With her brother’s next howl, Noémy sits up and crosses her legs. Jonathan’s body is flexed, the tendons in his neck strained like guy wires. Every beat of his heart ripples the thin white skin over his ribs.

In the absence of effective therapy or a cure for epidermolysis bullosa, caring for Jonathan requires constant vigilance. Avoiding potential pitfalls-things as mundane as zippers and oral hygiene-is perennially important. A zippered sweater might be easier for the teen to get in and out of, but the metal can rip his flesh. Brushing his teeth safely is a challenge, but not brushing leads to infection. In Jonathan’s world, staying healthy means risking further agony.

EB sufferers experience contact with their skin as stinging pinpricks. “The pain,” says Jonathan, “is basically indescribable.” To mitigate his suffering, the teen takes analgesics, including methadone, but they’re often inadequate. His doctors are struggling to come up with the right combination of medication to provide as much relief as possible. Where modern medicine falls short, Jonathan’s imagination-his “secret weapon”-comes into play.

“I slow my breathing and try to meditate,” he says. “I imagine a flame, and I throw the pain into the flame.”

Until 2014, the painkillers and mental exercises enabled Jonathan to regularly go to school in the neighbouring town of Embrun. These days, he misses class when he’s too tired from his bathing routine the previous evening; his attendance is also interrupted by trips to SickKids in Toronto. With the help of school staff and his teaching aide, he keeps up with his studies from home but still worries about falling behind his peers.

Jonathan was able to participate in gym-his favourite class-until four years ago. His earliest friends knew to be gentle with him, but not everyone followed suit. Between Grade 5, when he switched to a new school-leaving behind his close pals-and high school, there was bullying and name-calling. “My wounds smell,” Jonathan says with a shrug. “Of course, they do-they’re wounds.”

The harassment has largely ended now that his classmates have adolescent preoccupations, but it still affects him. “I was shocked by the bullying when I was little,” he says. “Now I’m mostly sad that I don’t have friends anymore.”

While Jonathan’s frequent seclusion at home allows him fewer opportunities to socialize in person, his online network continues to grow, thanks to his role at DEBRA. And even as he admits to his outsider status, he maintains his favourite people in the world are Noémy and Tina. “There’s being a mother and caring for a child, and then there’s Mom,” he says. “I wouldn’t be able to go on without her.”

“My life has been dedicated to making sure he’s got the best I can possibly give him,” says Tina. “His health has gotten progressively worse over the years. I plan to keep doing what we’ve been doing and taking every challenge straight-on. That’s what moms do: we help our kids through the bad and the good.”

“We’re at the baby stages of exciting research,” says Pope of the work being done in the field of epidermolysis bullosa (EB). Among the therapies showing promise are stem-cell injections, which involve introducing bone marrow cells into the blood, and gene therapy, where the patient’s own genetically corrected skin cells are grafted onto his or her wounds. Clinical trials are under way, and Jonathan is committed to doing his part to find medical solutions-even though a breakthrough might come too late for him.

In the busy waiting area at SickKids the morning of the amnion treatment, a toddler is splayed across two seats, playing with a plastic truck and burbling out engine sounds. This is the same lounge where Jonathan waited for a graft treatment last August, when his back was scrubbed of “non-viable” tissue, followed by the application of cadaverous skin to shrink the wound. On that occasion, Jonathan was ashen-faced and withdrawn. Pope thought he looked scared-just like any kid undergoing a major procedure. Still, she considers him exceedingly resilient, particularly in his choice to become an advocate for awareness rather than giving in to self-pity. “Jonathan’s subtype of EB is the most devastating medical condition we have,” says Pope. “It affects the whole body and causes such a significant amount of pain-and there’s no cure.”

Jonathan eyes the toddler’s truck as it crashes to the floor. When asked if he’s afraid of dying, the teen is quiet for several seconds. He’s searching for the right words.

“I want to have a regular life and to grow up to be an adult,” he says. A few more beats: “Yes, I’m scared.”

The admission seems to hearten him. “It’s supernormal to think about what’s ahead. But I’m still here. That’s the way I think of it. I’m still here.”

How you can support the cause:

- On Facebook, Jonathan Pitre shares updates with an online community of more than 2,000.

- DEBRA Canada’s website has additional information about EB, as well as a secure donation portal. Funds raised support awareness campaigns, as well as EB patients and their families.