For 15 Years, This Woman Assumed She Was Blind—Until a Second Opinion Turned Her World Upside-Down

After running some tests, the doctor delivered confounding news: “I don’t know how to tell you this, but there is nothing wrong with your eyes.”

In the mid-’90s, Connie Parke and her husband, Rob, settled in Anaconda, a tiny town tucked into the mountains of western Montana. When Parke, a mother of four, wasn’t bartending or working security at a hot-springs resort, she volunteered her time driving cash-strapped families the 12-hour round trip to the children’s hospital in Salt Lake City. Parke had experienced her own fair share of medical problems over the years: in the 1980s and 1990s, she beat uterine, ovarian and breast cancer, as well as lymphoma. By the early 2000s, she was, miraculously, in good health.

But one evening in 2003, while Parke, then in her early 40s, was driving back from Utah, she started seeing strange halos around tail lights and street lamps. “Wow, I must be tired,” she thought to herself. She’d worn glasses since she was six; she reasoned that she might need a new prescription.

Looking for answers

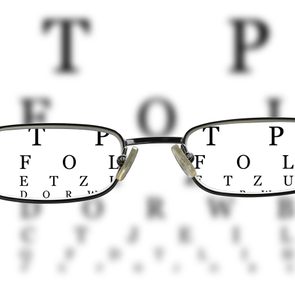

The next day, when Parke visited her optometrist, the tests he ran were alarming. She couldn’t see him wave his hand at the edge of her view, which meant she was losing her peripheral vision. He suggested it could be glaucoma, a group of eye diseases that damage the optic nerves. The condition is often caused by a buildup of pressure in the eye, which can lead to blindness within a few years if left untreated.

By the time Parke saw an ophthalmologist, three weeks later, her field of view was already murkier and narrower. The eye doctor agreed that it looked like glaucoma, but medicated eye drops, a typical glaucoma treatment, didn’t help, so Parke decided to consult more specialists around Montana and Utah. She wondered if her past chemotherapy was behind her vision problems, but the doctors dismissed it; it wouldn’t manifest years later. No one offered her a definitive answer or a treatment that would prevent her vision from getting worse.

As Parke consulted new doctors and tried to figure out what was wrong with her eyes, the halos morphed into clusters of foggy orbs. “It was like I was seeing fireworks that never went out,” she says. She stopped driving and relied on family to get around and run errands. She accidentally lit things on fire while cooking, walked into walls and tumbled up and down the stairs. Once, when she collided with a door frame, her son took her to the emergency room with a gash on her head. She was alarmed by her quickly deteriorating vision loss, but she held out hope that it wouldn’t be permanent.

About three months after her first symptom, Parke could no longer tell the bottles behind her bar apart. “Jim Beam and Jack Daniel’s look exactly the same,” she says. “I’d have a bill in my hand and wouldn’t know if it was a dollar or $100.” Unable to perform her job, Parke lost her shifts, so she applied for disability benefits.

To qualify, Parke needed to see a state doctor who was authorized to approve her for social security. She was surprised when the GP tested her eyes and delivered a new diagnosis. He believed that her retinas, the light-sensitive layer of tissue at the back of her eyes, had become detached—and that they couldn’t be fixed. “You are blind,” he said matter-of-factly, explaining that she’d have to learn to live without a sense of sight. Parke was crushed, but she believed the diagnosis. After so long without answers, this one seemed to make sense.

Adapting to a new reality

Unable to see, read or work, Parke fell into a depression. Her daughter Barbara helped her look for schools for the blind—where she could learn how to read braille and use a cane and other assistive devices—but there were none in Montana. They moved to Colorado, where they’d be closer to a school and Parke’s family. Rob found a house with a nearly identical layout as Parke’s childhood home, which helped her get around. She got to know her grandkids—nine in total—by the shapes of their faces. The company of relatives and her service dog, Talulah Mae, kept Parke’s spirits up through it all.

Over the next 15 years, Parke decided not to let blindness stop her from doing the things she loved. She fished, skated and kayaked, following the sound of Rob’s voice as she paddled along the surface of the water. She even developed a sense of humour about her new reality. Once, while Barbara was driving her somewhere, she stuck her cane out the passenger window. “What are you doing?” her daughter asked, confused. “I’m trying to see where we’re going,” she replied with a chuckle.

One more opinion

In October 2018, Rob got his eyes checked for cataracts at UCHealth, the University of Colorado’s hospital, and convinced Parke to see a retina specialist there, figuring it couldn’t hurt to get one more opinion, even after so many years. “You have nothing to lose,” he assured her. Although reluctant, Parke agreed.

After running some tests and scans, the doctor at UCHealth delivered some confounding news: “I don’t know how to tell you this, but there is nothing wrong with your eyes.”

Parke was floored as the doctor explained the truth behind her blindness. Her retinas weren’t detached. She just had a severe case of cataracts. A common 15-minute surgery could improve her vision. “I was momentarily angry,” she says. How did so many doctors miss this? she wondered. She blamed herself for not seeking out more opinions. “I didn’t have to be blind for 15 years.”

The doctor sent Parke to Dr. Jeff SooHoo, a UCHealth ophthalmologist who could surgically remove the cataracts, one eye at a time. “I definitely tried to undersell it,” SooHoo says. “For some people, you take out their cataracts and they still can’t see. But it usually won’t make things worse.”

The following month, on November 12, 2018, SooHoo operated on Parke’s right eye—making a corneal incision, removing the cataract with ultrasound technology and then replacing it with a plastic lens.

The next day, when a nurse removed the patch from Parke’s eye, she immediately burst into tears. She couldn’t believe it. She could see again. “I saw every individual strand of hair on the nurse’s eyebrow,” she says.

Incredibly, when SooHoo tested Parke’s eyesight after the operation, she could read the 20/20 vision line on a wall chart without glasses. Her vision was better than ever.

A sight for sore eyes

After her appointment, Parke laid eyes on some of her grandkids for the first time—she couldn’t tell a pair of twins apart, because she only knew the feel of their faces. It was jarring for her to see a grey-haired woman in the mirror, but she was more preoccupied with all the beauty she had been missing: squirrels jumping from tree to tree, thick fractal snowflakes, buds on branches. “I’d just sit there, waiting for the thing to bloom,” she says. She often found herself weeping with joy.

Parke had the cataract in her other eye removed a few weeks later and now has near-perfect vision. She repainted her house, got her driver’s licence and found a job as a care-unit clerk at UCHealth, the hospital that helped her.

She doesn’t dwell on the erroneous information that previous doctors provided her. “The minute I walked out of that hospital, I wasn’t even mad about being misdiagnosed,” she says. “I was just so happy to see.”

Next, find out the terrifying reason behind this 38-year-old woman’s vision loss.