Yes, Your Seasonal Allergies Are Getting Worse

Climate change is exacerbating seasonal allergies for one in four Canadians who dread the first sniff of spring. Here's how to minimize your exposure.

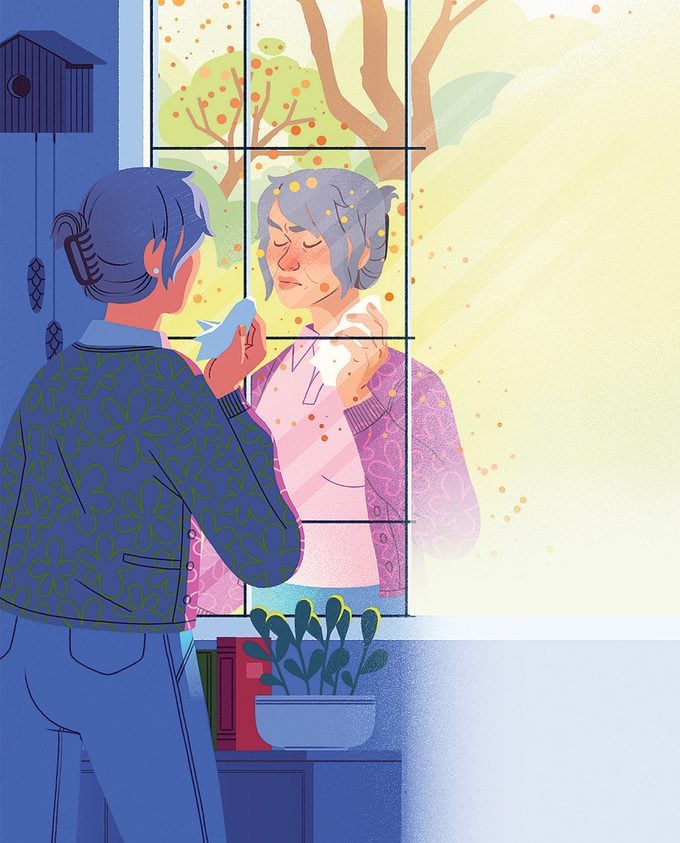

Ah, the first signs of spring—and the first sign of seasonal allergies. It could be the buds on the trees or the warm sunshine. Or maybe you know it’s spring because your nose is running, you’re sneezing and your eyes are red and itchy.

More than nine million Canadians suffer from seasonal allergies, which can start as early as February on the west coast and last well into the summer months. They can be triggered by pollen from grass, plants such as ragweed and goldenrod, and budding trees such as birch and maple.

“I’ve had allergies for 10 years, but they have been getting worse over the last few seasons,” says Toronto-based Patrick Boyd. The 30-year-old isn’t the only one experiencing a spike in the symptoms of allergic rhinitis, which typically include a constantly running nose, watery, burning or itchy eyes and a scratchy throat. Across the country, seasonal allergies are on the rise as the peak pollen months start earlier, last longer and have become more intense. In 2023, Toronto experienced its worst allergy season of the last five years.

“We have seen pollen getting worse in Canada,” says Daniel Coates from Aerobiology Research Laboratories, a Canadian company that monitors airborne allergens (and provides pollen forecasts to the Weather Network). “You have cycles up and down, but if you do a trend line between all the years of data, you can see that pollen levels are rising,” he says.

Experts believe that climate change could be to blame. “What’s really been throwing everything off is the fact that our winters are lasting longer, and then we get thrown into basically summer temperatures,” says Dr. Anne Ellis, a clinician-scientist and chair of the division of allergy & immunology in the department of medicine at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario.

This sudden change in temperature causes the trees to panic and “bomb” us with pollen instead of slowly budding and blooming, she says. And, since the trees are releasing pollen much later in many areas across the country, they are now overlapping with grass-pollen season. “For people who are allergic to both, they’re getting a double whammy,” says Ellis.

To make matters worse, allergic rhinitis is aggravated by the very thing driving climate change: air pollution. Research from Ellis’s lab has shown that diesel exhaust makes ragweed allergy symptoms much worse. “If you’re in an urban area with traffic-related air pollution, this is likely to intensify your symptoms,” she says. (Interestingly, many cities also unwittingly exacerbate the air-quality problem by planting too many male trees—which release lots of pollen—since they don’t produce messy fruit or flowers, she says.)

Fortunately, you can minimize your exposure on peak pollen days. First, to know when those days are going to be, follow the pollen forecasts from your local weather source. Then, when tree, grass or weed pollens are in full force (usually between late spring and mid-summer), practise good allergy hygiene by not hanging laundry outside to dry, keeping windows closed and installing a HEPA filter on your furnace. Exercising indoors, delegating yard work and gardening chores that stir up allergens and showering after being outdoors will all help to minimize your exposure.

Despite, or maybe in part because of, how common spring allergies have become, we tend to dismiss them as just the spring sniffles. But this does a disservice to people who are suffering with the symptoms, day in and day out, sometimes for months at a time, says Ellis. “Nobody dies of hay fever, but it has a huge impact on quality of life,” she says.

Boyd describes often feeling irritable due to the discomfort in his eyes and nose. “Allergies also give me headaches,” he says. Like roughly three-quarters of people with allergic rhinitis, he has never seen a doctor about it, but he says his allergies have gotten so bad that he’s considering making an appointment.

“If over-the-counter antihistamines aren’t working for you, it’s time to see your physician,” says Ellis. Your doctor can prescribe better antihistamines, nasal steroids, eye drops and, if necessary, refer you to an allergist who can determine if you’re a candidate for immunotherapy. This can involve sublingual tablets or a series of allergy shots that slowly minimize your body’s reaction to the allergen so you don’t experience as many symptoms, says Ellis. “The most important thing is not to suffer in silence.”