Decoding the Blues: Treating Depression

The delicate art of treating depression.

“A grey wall now, clawed and bloody.

Is there no way out of the mind?

Steps at my back spiral into a well.

There are no trees or birds in this world,

There is only sourness.”

-Apprehensions, by Sylvia Plath

In 1953, 20-year-old Sylvia Plath submitted to her first round of electroconvulsive therapy-one of many treatments she would receive in the quest to relieve her ever-intensifying depression. She chronicled her illness in The Bell Jar-before taking her own life at age 30. Now acclaimed as a classic portrait of mental illness, the novel is an example of the agony of depression and the demoralizing process sufferers endure in pursuit of a cure. The condition has been documented in medical literature for nearly 2,500 years and has confused us for just as long.

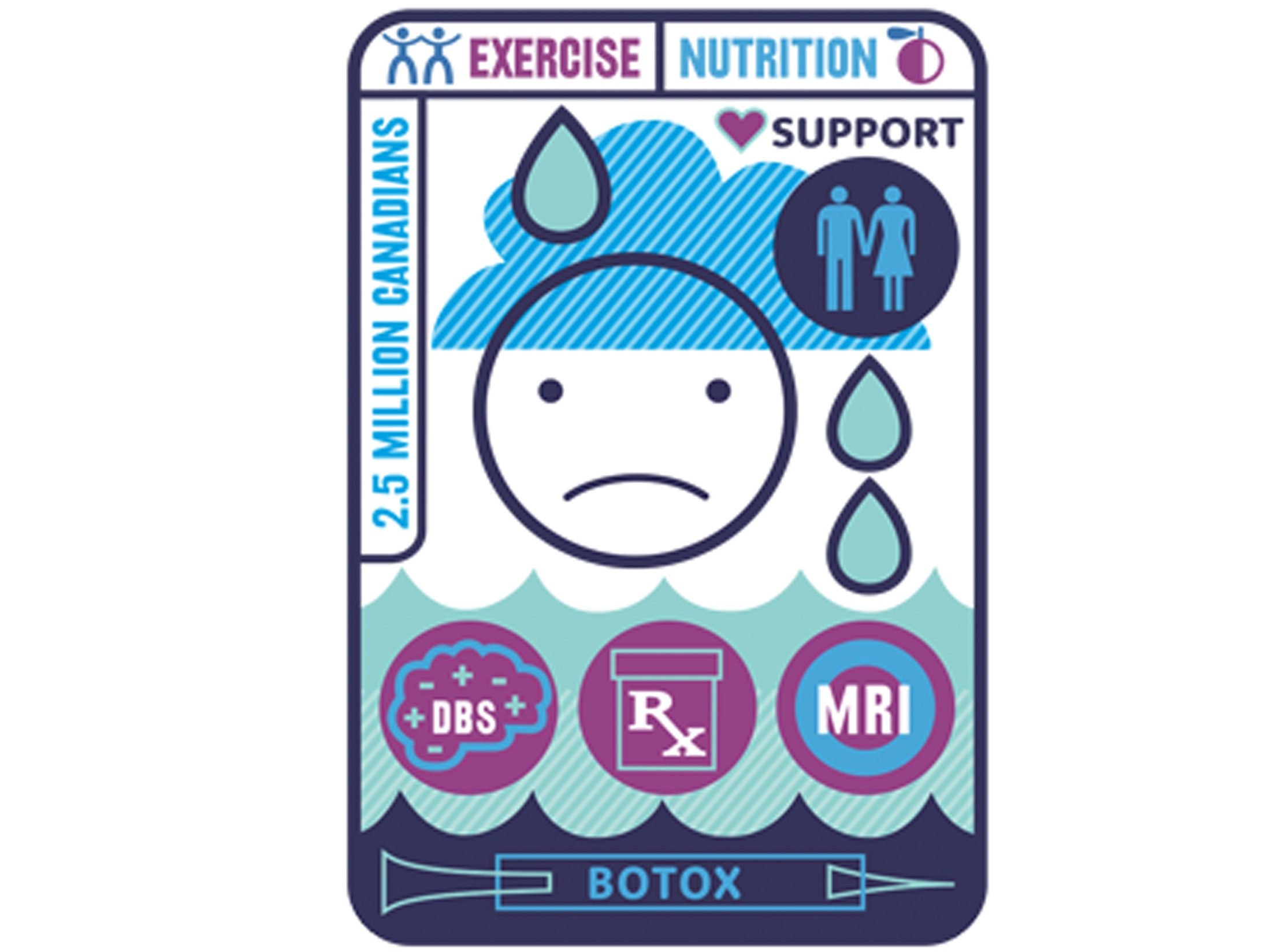

Two and a half million Canadians over 18 will suffer from a depressive illness in their lifetime, making it one of the most common mental health disorders in the country. Despite its pervasiveness, diagnosing and treating the condition has always been a mix of art and science, says Dr. Beth Robinson, director at the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy

Association. In fact, the first antidepressant drug-one of the primary treatments for depression today-was discovered by accident in 1951, when doctors tested the efficacy of a pill, iproniazid, on tuberculosis patients. The drug had some effect on TB but a dramatic effect on patients’ moods: sufferers became increasingly happy.

The divide that characterizes depression research today-is this a disease of the mind or the body?-shows how mysterious the disease remains. Our approaches to it, from bloodletting to asylums, have shifted as each era’s experts have tried to decode the condition. “What makes depression different from something like diabetes is that the research strategies tend to work backwards,” says Dr. Sidney Kennedy, professor of psychiatry at the University of Toronto. “Effective treatments are used to further understand how the disorder develops.”

Research is ongoing into effective new medications for depression-such as ketamine, a popular street drug-as well as a procedure called repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, or rTMS, which uses pulsing magnetic fields to influence brain activity. Doctors are also turning to a new frontier in treatment called deep brain stimulation (DBS). Developed as a therapy for treatment-resistant depression, which afflicts 20 to 30 per cent of patients, it involves implanting electrodes in an area of the brain, which are then connected to a pacemaker in the chest. Early studies on the surgery have shown remarkable success. “Now depression is diagnosed by having the patient self-report symptoms, in addition to physician observation. But in the future, doctors could add biological tests-such as functional MRIs-to diagnose depression,” Kennedy says.

Other remedies, including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), can also influence brain pathways, similar to DBS. CBT involves patients repeating certain exercises-such as scoring their moods throughout the day-that promote more positive thinking habits. An increasing number of Canadians are seeking out CBT for mental health issues; some studies have found it as effective as pharmaceuticals for depression. And though current thinking on the disorder addresses its psychological and social aspects as well as the physical, establishing depression firmly as a medical disease could go far in helping people feel less ashamed of their condition and encouraging them to seek treatment. “Therapy can, and often should, be augmented with medication when necessary, as well as with nutrition, exercise and interpersonal supports,” Robinson says. “Humans are multi-faceted and so is depression. It makes sense that treatment would be complex, too.”

The Breakthrough:

Can warding off depressive feelings be as simple as turning your frown upside down? According to recent studies, the answer could be yes. One, by Dr. Eric Finzi and Norman E. Rosenthal published in the Journal of Psychiatric Research in May 2014, found that Botox might be an effective treatment for depression-patients reported feeling less depressed six weeks after being injected. Researchers at the Hannover Medical School in Germany and the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center have also conducted trials with promising results. The idea behind the studies is known as the “facial feedback hypothesis,” which suggests that facial expressions induce the mood they’re supposed to evoke. That is, you aren’t frowning because you’re upset; you’re upset because you’re frowning. When the muscles responsible for showing sadness are paralyzed, the theory goes, we’re prevented from getting stuck in those emotions.

Ask an Expert:

Dr. Beth Robinson, director of the Canadian Counselling and Psychotherapy Association

Q. What’s the difference between sadness and depression?

Sadness is pathologized in our culture-think of how many times you have heard someone say, “I’m depressed!” when they’re a bit down. But it’s a normal response to upsetting life situations. Depression is a larger and more severe condition of which sadness is one symptom. Clinical depression includes feelings like worthlessness and guilt, along with changes in eating and sleeping patterns, in addition to sadness.

Q. When should I seek professional help?

When sadness is starting to interfere with your job, it’s time to consult a professional. Your first port of call should be your family physician, in order to rule out any underlying medical conditions that can cause or masquerade as depression, such as some brain injuries or thyroid disorders. Once medical conditions are ruled out, your family doctor may be able to refer you to a psychotherapist or a psychiatrist.