My Dad Was Diagnosed With MS at 43—And It Changed Our Family Forever

For my mother, caregiving was filled with challenges—and triumphs.

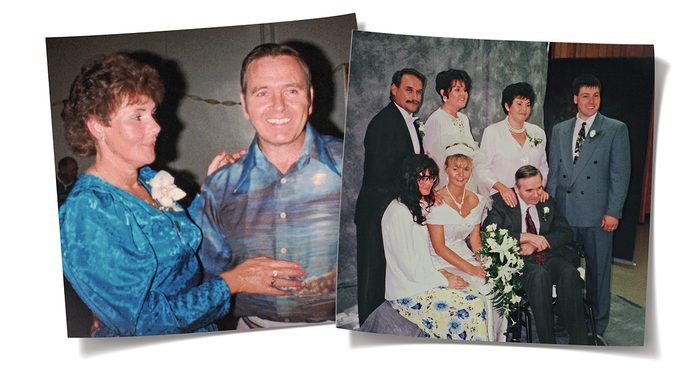

My earliest exposure to family caregiving was personal. In December 1980, during my first term at nursing school, my father, Don Polley, was diagnosed with primary progressive MS. Dad was 43 and Mom was 41. Their lives changed forever. Our lives changed forever. About 12 years after my dad’s diagnosis, my mother, Myrna, had to retire from her nursing position, much sooner than she’d planned, to become his caregiver at their home in Nova Scotia.

Far less was known about multiple sclerosis at the time, and fewer drugs and interventions were available for symptom management. The condition becomes debilitating over time, but the speed and severity of the disease are different in everybody.

Dad quickly went from his full-time work as a manager at the Nova Scotia Department of Mines and Energy to part-time, until he was fully retired and on a disability pension at 46. Still, he stayed involved with his community-service work, reading his mail and watching stocks and bonds. He even took his stockbroker course but couldn’t write the test because his mind wasn’t as sharp or as quick as it had been.

Over time, he progressed from crutches to a wheelchair. Being in the wheelchair affected his social and community life, and with his general deterioration came fatigue and decreased muscle tone. When his speech was affected, he found it increasingly difficult to hold his head upright without support. Ultimately, he stopped participating in his service clubs and church. It was a sad and significant marker of the effect the disease was having on his life.

Mom and Dad had a solid marriage. They respected each other and showed love and affection openly. They also had no problem saying when they were upset about something, though they rarely directed it at the other.

My mother was a strong woman, but the life she had enjoyed during the first 20 years of marriage was long gone. As is the case with many family caregivers, Mom’s health was affected by its demands. In addition to developing high blood pressure during her time caring for Dad, she often experienced stomach upset and sheer exhaustion.

“It’s hard,” she often said. “It’s not the life we imagined. He’s not the husband I married.” Their life changed dramatically as a new reality set in. She obtained whatever care and equipment Dad needed, learned new skills and advocated for Dad—a lot. Mom was pragmatic. A doer. And she faced caregiving head-on. There was no alternative.

We still don’t know enough about MS. This disease of the central nervous system, which disrupts the flow of information within the brain and between the brain and the body, is unpredictable. Unfortunately, Dad’s health deteriorated rapidly.

My father was never confused, but he couldn’t think or process information as fast as he used to. He grew to rely on clichés, which drove Mom nuts. I remember walking into the den on one of my visits home—I had moved west to Manitoba soon after graduating from university. Dad was sitting in his dark blue recliner rocker, next to a steel pole my brother had drilled into the floor and the ceiling. Dad hung on to it as he manoeuvred from his wheelchair to his recliner. He used it to pull himself up if he needed to reach something or take pressure off his back and bottom as he changed positions.

I swung myself around his pole as I reached down to give him a hug and a kiss. “What’s new? How are you?”

“Oh, you know, dear, the same. They treat me like a mushroom around here. They keep me in the dark.” He chuckled, proud of his wit.

As I walked back through the kitchen, I stopped to hug Mom. She rolled her brown eyes and shook her head. “I heard your father and those damn clichés! He just can’t help himself.” She paused before continuing. “He either says that he’s just like a mushroom, call a spade a spade, or you’ve seen one, you’ve seen them all.”

She took a deep breath and laughed. “Goodness,” she said. “I’m going to dive off the deep end.”

“Mom, I don’t know how to tell you this, but ‘dive off the deep end’ is a cliché.” We both cracked up.

There is caregiving crisis in North America, and around the world. Compounded by a demographic shift with aging boomers, the problem will only grow. It is estimated that 46 per cent of people over 15 years of age have provided care at some point.

I’ll never forget the day of Mom’s big confession. It was about seven years after Dad’s diagnosis, around the time she retired to take care of him full-time. “What you kids and everybody else see on the outside is not what I really feel,” she told me. “Inside I’m a seething b***h.” I was shocked that she said it with such conviction. I didn’t have a clue how to respond.

My mother could be quite funny, or at least she used to be. She was smart, compassionate and to me, the consummate caregiver. Always sharp-witted and honest, she told me that she couldn’t fully embrace the b***h thing or she might be gone forever.

I knew what she meant. Dad’s diagnosis had ripped the life my parents had planned right out from under them. How could she not feel anger and resentment? And yet she believed that if she let that bitterness take over, she wouldn’t be able to go on and live the life they had now—the new normal.

My parents still found joy in some of the old habits, like watching their favourite TV shows together and eating meals they loved. Many people take comfort in the familiar. Indeed, that’s a big part of learning how to cope: understanding that, while so many things have changed, not everything has. This is as true for relationships as it is for routines.

Dad was never demanding. Thankfully, he never became nasty or difficult, or had personality changes, traits that sometimes affect people with MS. For that, I often said a prayer of thanks.

My father loved and appreciated everything Mom ever did for him, no matter how big or small. And she was never angry at Dad, just at the tragic, horrid circumstances caused by a chronic, life-limiting illness. Mom was mad as hell that her handsome, strong, capable husband got one of the worst, most debilitating and often family-destroying diseases of the 20th century. There was no cure, and for Dad, there was little treatment.

It was unbelievable to us kids that our family future was no longer what we’d had in mind. Dad’s life was taken from him and Mom’s from her. Dad comes from a family of long-lived people, and MS doesn’t kill you in and of itself (the patient usually dies of some other cause or complication, rather than the disease). So Mom knew she was in for a life sentence.

Caregiving exacts a toll. Mom was pissed off at the world, but there was a lot of love sprinkled in. Through the 21 years of caregiving for Dad, there was laughter, as well as weddings and babies. There were wonderful outside caregivers, and there were those who didn’t seem to care much at all. There were system obstacles—lots of them—to overcome. Without love, I’m not sure what would have happened to us. We were in it for the long haul. There was no escape.

The flip side of all the sadness, burden and frustration is that most caregivers, like my mom, wouldn’t give up their role for any reason. Citing love and a compulsion to care for their loved one, they say “If not me, then who?” Caregivers want to give, to help, to be there. Good thing too, because the role is all-consuming—physically, spiritually and emotionally. It is unreal. It is real. It is pain and suffering, love and courage. It is also life in its every breath.

If I had to sum up what I observed about my mother’s caregiving, I would call it “resilience in action.” Her behaviours were part of what makes a caregiver resilient—knowing and setting her own boundaries, being aware of her sense of self, not being a martyr. Mom would remind Dad that she was up with him at night, for example. Or tell him when he was fine to wait for her for a time, that everything wasn’t always such an emergency that she had to stop what she was doing and run to him.

A non-resilient caregiver might not view things the same way. They might jump to conclusions, such as telling themselves they are a failure, that they should do more, that they need to sleep in the same room as the person they care for, even if it means doing so in a chair.

Mom told Dad that she had things she needed to do for herself: time in the morning to shower, have a coffee, read the paper or run errands. She was action-oriented and recognized that in order to get everything done, she had to get up at 6 a.m. She needed some time for herself—and for her, it was those few moments of quiet in the morning before tackling the day.

Our family meals went from lots of conversation and laughing to no laughing—only because Dad would laugh and start choking on his food or his saliva, so we had to be mindful. In the later years, taking two hours to feed Dad his supper was the norm.

Over time, Mom accepted some outside help. It wasn’t a lot of time—two hours each morning—but it got Dad ready for the day. Ultimately he even required feeding, which the paid caregivers began to do.

Gradually, Mom had to take over the feeding because they could no longer feed him without causing him to choke. Most of them either couldn’t or didn’t give Dad the time to eat that he needed. Dad was worsening, and eventually it became near impossible for Mom to get much food into him.

“Kimmie, I don’t know how much longer I can keep this up,” she told me one day. “He takes so long to chew that he’s falling asleep with food in his mouth. He chokes and chokes. I don’t know what I should do. If I don’t feed him, he’ll die, but I can’t just sit by and watch that.”

I asked, “Did you talk to him about it?”

“No. What’s the point? The next thing is a feeding tube, and I don’t think he’d want that.”

Not many people in Dad’s condition would have been fed so well. In fact, our family doctor often said, “Myrna, the only reason Donnie is still alive is because of love and the good nutrition you give him.”

Now I knew that she couldn’t go on as they were any more, and neither could Dad. I approached the side of Dad’s bed and asked, “Dad, you hear what Mom and I are talking about in the kitchen, right?”

He nodded as best he could, looking straight at me. He could no longer speak but he certainly understood us, so we always included him in our conversations.

“We just need to know what you want Mom to do,” I said. “We know it’s hard on you, choking on every meal. We need to know what you want. We can place a feeding tube in your stomach.”

He mouthed a definite “No,” then shook his head.

I nodded and replied, “Okay, then. That’s what Mom and I thought you would say.”

It wasn’t too long after this conversation that Dad died. He got progressively worse, dependent on Mom for everything. She never received more than two hours of help per day, but during the last few weeks the nurse case manager checked in with Mom more often. Our plan was that Dad would die at home.

One day Mom called to say that Dad was failing and it wouldn’t be long. I booked the earliest flight I could for myself, my husband and our one-year-old. That night, as I was packing and making arrangements, Mom held the phone to Dad’s ear so I could say goodbye. I was crying and told him that if he couldn’t wait for me, it was okay. My sister who lived in the United States was also flying in, but my sister and brother who lived near my parents were with them. A few close friends and other family, including our grandmother—Dad’s mother—visited throughout that day and evening.

Dad died at home at 9:30 in the morning on May 16, 2001, about the time our plane was landing. He had most of his family around him and was as comfortable as possible. He was 64.

Through the years of looking after Dad, there were few, if any, signposts. Getting help at decision points was challenging, and finding our way was often a matter of trial and error. Knowing what choices were available in certain situations would have been helpful, as well as understanding how various options might impact the trajectory of Dad’s life, or affect Mom as his caregiver.

Having someone, like a caregiver coach or navigator, would have helped. Mom was left to her own devices when it came to finding the necessary equipment and supplies. Every time Dad deteriorated or faced a new phase with his MS, we would be confronted with new decisions to make.

Unfortunately, all too often caregivers feel frustrated, short on time and energy and even demoralized. They learn that putting one foot in front of the other is the only way to progress.

No one could have done more for my father during his years of illness than my mother. What I witnessed informed my world view of family caregivers. They do whatever it takes for their loved ones—no matter what, regardless of the circumstances or difficulty. They put the care and the caregiving for the other above their own needs—usually because no one else will; perhaps no one else can. And it’s why I know that caregivers deserve help, support, respite and attention.

I hope I can measure up when it’s my turn to care. Because one thing I know for sure is that we—myself, my siblings, my friends—will all be called to care.

Kimberly Fraser, Ph.D., is a retired nurse and former professor of nursing at the University of Alberta. She ran a home health-care business in Edmonton and was the past president of the non-profit Caregivers Alberta.

Excerpted from The Accidental Caregiver, by Dr. Kimberly Fraser. Copyright © 2022, Dr. Kimberly Fraser. Published by Sutherland House Books. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Next, check out Kimberly’s self-care tips for caregivers.