How to Heal Your Gut

A decade ago, Kaitlyn, a 28-year-old support worker living in Ontario, had become very ill. She had painful constipation and was contracting fevers and losing weight. “If I ate too much, I would vomit,” she says.

After tests ruled out Crohn’s disease and colitis, Kaitlyn’s family doctor diagnosed her with irritable bowel syndrome, a chronic disorder that causes cramping, pain and bloating along with constipation or diarrhea.

IBS isn’t something that can be cured but, rather, managed through lifestyle changes. A dietitian suggested to Kaitlyn that the bacteria that lived in her intestines—collectively known as the gut microbiome—might be out of balance, contributing to her condition. She recommended Kaitlyn take probiotics—pills that contain specific strains of bacteria—to help put things in order.

After only a few days of taking the probiotics, Kaitlyn felt a lot better. “The pain and fevers went away, and I was able to eat without getting sick,” she says. Although she still needed to avoid specific foods that trigger her IBS, she gained back some of the weight she had lost.

But probiotics don’t work for everyone, and we don’t really know why. Although the state of our gut microbiome impacts many facets of our physical and mental health, scientists have had the technology to study it for only the last 15 years. That said, discoveries are being made every year. Here’s what we know about the gut, how to tell if it’s out of balance, and how to make it as healthy as possible.

How does a gut microbiome form?

Imagine a jar of fermented food, like sauerkraut, which is full of bacteria. In the case of the cabbage that transforms into this dish, the bacteria that already live on the cabbage flourish when you cover it in brine and put it into a sealed container. Inside that oxygen-deprived space, those bacteria break down the components of the food—like carbohydrates—and release acid, which gives sauerkraut its tangy flavour. A similar process happens inside your intestines every time you eat: bacteria break the food down, transforming it into crucial vitamins, amino acids, chemicals and, yes, gas. (Here’s what your farts can reveal about your health.)

All those bacteria start colonizing you the minute you’re born. Babies who are born vaginally have different microbiomes than those who are born by C-section, because the former are exposed to more of their mother’s bacteria. After that, you pick up more bacterial strains from breast milk, your house, the environment outside, contact with other people, the food you eat and even the family dog.

By the age of three, your microbiome has pretty much settled into how it will look when you’re an adult. The different types of bacteria that live in your gut help you digest food, but they also impact other aspects of your body, as well, including your immune system, your brain and your cardiovascular health.

What bacteria are in your gut?

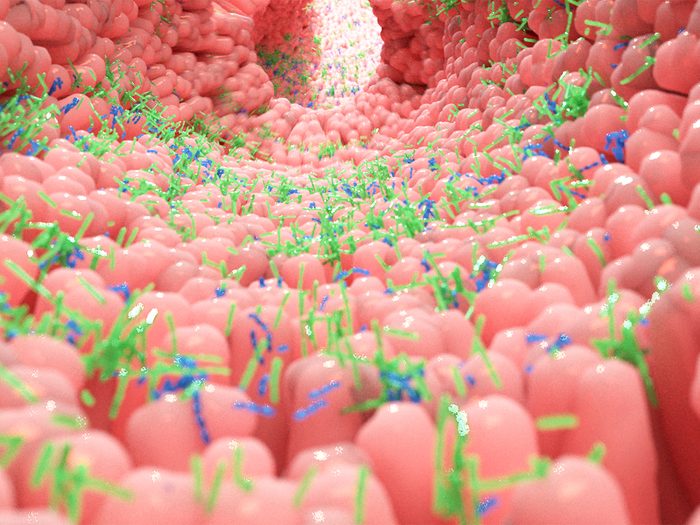

“Your gut is like its own ecosystem,” says Sean Gibbons, a microbiome researcher and assistant professor at the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle. “It’s warm, humid and wet—like a rainforest.” And, he explains, like any thriving ecosystem, your gut is healthy when it’s diverse, with hundreds of different types of bacteria flourishing.

Two of the most important types of bacteria in a gut system are Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes, which feast on dietary fibre and break down complex carbohydrates. Both of them also churn out short-chain fatty acids, microscopic compounds that help maintain the integrity of the gut wall. (That barrier is supposed to be porous in order to let nutrients through, but if it’s too porous, that can lead to inflammation.) They also have anti-inflammatory properties and can promote brain health.

You want to feed those two types well, because if there’s not enough food in your system, they’ll turn to their secondary source: you. “They will actually start to eat your gut mucus,” explains Gibbons. If that happens, many bacteria in your gut that wouldn’t bother you with an undisturbed gut surface will suddenly be seen as outside agents from your immune system, setting off a response that can lead to inflammatory bowel disease and other gut problems.

Signs Your Gut is Out of Balance

You have a stubborn bowel condition

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis—known together as inflammatory bowel disease—cause inflammation and breaks in the lining of the intestines, leading to pain, diarrhea and weight loss. About one in 150 Canadians has IBD, and according to Dr. Eugene Chang, director of the Microbiome Medicine Program at the University of Chicago, its exact cause is still unknown. He says, however, that researchers think affected people are genetically predisposed to have an overactive immune system, and that their microbiome changes in subtle ways to prefer bacteria that thrive in that inflammatory environment. “Those bacteria further activate the immune system, and it’s a vicious cycle that eventually triggers IBD,” explains Chang.

IBS, which is much more common and affects up to 11 per cent of people worldwide, shares many of the same symptoms as IBD but without the inflammation and ulcerations. Like IBD, the exact cause of IBS isn’t clear, but studies have shown differences in the microbiome of IBS patients—and there are anecdotal reports that probiotics can help some of them feel better.

Your medications aren’t working

The medicines doctors prescribe don’t always work, and in some cases, the gut microbiome may be to blame. Just like microbes break down the fibre and starches in our food, they can also break down pharmaceuticals, making them act unpredictably.

In fact, a 2019 study from researchers at the Yale University School of Medicine looked at 271 drugs taken orally and found that the gut microbiome affected two thirds of them, with the bacteria consuming about 20 per cent of their active ingredients. That means, for example, that if you have too much Eggerthella lenta—a bacterium found in about a third of us—the commonly prescribed digoxin might not help your heart disease symptoms.

This effect on medicine has even larger implications for cancer treatment. Recently, researchers found that the gut microbiome can affect the progression of some types of cancer, and that it also affects who responds to immunotherapy and bone marrow transplants.

All of the above has given birth to a new field: pharmacomicrobiomics, the study of how your gut microbiome affects a drug’s actions. In 10 to 15 years, your doctor may be able to test your microbiome through a stool sample and then modulate the dose—or possibly prescribe a probiotic—to make your pills work better. And clinical trials are currently investigating whether cancer patients are more likely to survive if they’re given tailored probiotics, a special diet or a fecal transplant—a small bit of poop from someone else that could reset your gut microbiome.

Find out the surprising things your poop can reveal about your health.

You struggle with your weight

“Two decades ago, we all thought that obesity and metabolic disorders were just how much you ate,” says Chang. “But it turns out that the gut microbiome seems to play a really important role.”

The connection is clearest in mice: when researchers from the Washington University School of Medicine transplanted stool samples from obese and thin people into the rodents, the animals who received fecal transplants from the obese participants gained more weight and put on more fat than the ones who received them from the healthier participants, even when the mice all ate the same low-fat diet.

There’s some evidence from humans, too: for a 2020 study, Belgian researchers gave people who had insulin resistance and were overweight or obese a bacterium that’s found to be more common in the guts of lean men. Similar to the mice experiment, the new bacteria lowered participants’ insulin resistance, and they lost more weight and fat than a placebo group.

You’re depressed

We think of mood disorders as originating in the brain, but it appears your gut can be a source of them, as well. A 2019 study found that people with depression had fewer Coprococcus and Dialister than most people, and other research has found that mice who receive stool transplants from depressed humans get depressed, too.

So could changing someone’s gut microbiome improve their mental health? The research is still emerging, but a 2017 Australian study found promising results. It looked at people with major depression who were on medication or therapy. Half of the participants kept their treatment regimes while also switching to a Mediterranean diet, which is rich in microbiome-enhancing whole grains, vegetables, fruits and lean protein. That group had a much greater reduction in their depression than the others.

Here are the signs of high-functioning depression you might be ignoring.

You have allergies

A diverse microbiome can help regulate your immune system, especially early in life. So if your immune system is hypersensitive because your microbiome isn’t up to the job, it increases your chances of having allergies, asthma and eczema.

That’s why exposure to a variety of bacteria, starting right when you’re born, is so important. Kids who are born vaginally are less likely to have allergies than those born by C-section—and so are people who are raised on farms, have pets or grow up with germy older siblings in the house. The thing is, all this needs to happen really early in life. “After one year, it’s too late. The immune system has already made up its mind,” says B. Brett Finlay, a microbiology professor at the University of British Columbia and author of Let Them Eat Dirt.

According to Finlay, antibiotic use can also have a big impact: as it wipes out the bacteria making you sick, it will also indiscriminately wipe out bacteria that keep your gut diverse and healthy. That raises the risk your gut microbiome will be inadequate for warding off the conditions that cause allergies, asthma and eczema. In fact, Finlay and other UBC researchers found that people who had been prescribed antibiotics before age one were twice as likely to develop asthma by age five—and the risk increased with every course of the medication.

The impact of a less diverse gut persist into adulthood. When researchers with the American Gut Project analyzed the gut microbiomes of more than 1,800 people with allergies, they found that those with seasonal allergies and nut allergies had less diversity in their gut.

Discover the sneaky reasons you’re bloated all the time.

How you can improve your gut microbiome

There isn’t a magic all-purpose prescription that will improve everyone’s gut health, though researchers are hopeful that within five years, microbiome tests will be detailed enough to prescribe personalized probiotics or make other patient-specific recommendations. But there are some changes experts recommend that can help right now.

1. Eat more fibre

One of the most well proven connections between lifestyle and gut health is that eating more fibre creates a better microbiome. Fibre is the main food source for the most important gut bacteria, so not getting enough starves them, and many of them die off. That means they may produce fewer of those short-chain fatty acids and other important components of your diet, and they’ll begin consuming the mucus that lines and protects your gut.

Unfortunately, most people across Western countries don’t get enough fibre. For example, according to Julie Thompson, information manager at the charity Guts UK, even though U.K. government guidelines recommend eating 30 grams of fibre each day, and the average person eats only 19 grams.

To get your 30 grams, focus on eating five servings of fruits and vegetables each day, as well as a whole-grain carbohydrate at every meal.

Here are 12 high-fibre foods worth adding to your cart.

2. Diversify your diet

Your overall goal for gut health is to create a diverse microbiome. And it’s not just fibre that provides sustenance for good bacteria—other things in our meals do, too. If you eat a large variety of foods, including many different types and colours of fruits and vegetables, that variety will promote a healthy gut.

Not all food is helpful: high-fat processed foods deplete healthy bacterial strains and make your gut less diverse in general, says Chang. In fact, if you were to suddenly swear off eating your salad in favour of fries, he adds, “Your microbiome would change within 24 hours, with a decrease in the healthy microbes that plant fibre promotes.”

Find out the foods everyone over 50 should be eating.

3. Avoid unnecessary antibiotics

Antibiotics are a literal lifesaver when needed, but they do tend to throw our gut microbiome off balance by killing even the bacteria you want to be in there, like the gut-wall maintaining Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. Usually, a plentiful amount of those two can crowd out bacteria that can make you sick, just as it’s harder for weeds to establish themselves in a lush lawn than in unplanted dirt. But when antibiotics do their job of destruction, bad bacteria can take over before the good have a chance to re-establish themselves. That usually comes with a telltale result that something is off: diarrhea. While most healthy gut microbiomes can bounce back from that, if yours is already unbalanced, Gibbons says antibiotics could lead to issues like IBS.

To help prevent antibiotic-caused diarrhea, you can take a probiotic the same day as you start your antibiotics. A 2017 University of Copenhagen review found that only 8 per cent of people who took probiotics developed diarrhea when they took antibiotics, compared with 18 per cent of those who took placebos.

Most importantly, make sure you really need an antibiotic before you take it. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at least 30 per cent of antibiotic prescriptions are unnecessary.

Find out more medication mistakes that could be making you sick.

4. Talk to your doctor about probiotics

As mentioned, probiotics have been proven to prevent diarrhea while taking antibiotics. They may also protect people when they’re travelling to a country where the bacteria in the food and water are different from those back home. Most usefully, though, they may help people who have IBS, although their effectiveness has yet to be confirmed in studies. Anecdotally, however, experts say they can work for some people and continue to encourage patients to try them for gut-related issues. It’s best to try them only at the direction of a health care provider, who can suggest specific brands so you’re not wasting your money on random products. In the meantime, scientists are working to understand them better. “Within the next five to 10 years, I believe we’ll start to see medical grade probiotics hitting the consumer market,” says Gibbons.

Here’s more on what probiotics can (and can’t) do.

5. Fit in a workout

Regular exercise changes your gut microbiome for the better—at least according to some early research on the topic. A 2016 University of British Columbia study found that athletes with the best cardiorespiratory fitness levels—a marker that measures how well your body can move oxygen to where it’s needed—also had more diversity in their gut health. Another study, from Spain, found that women who did three hours of exercise a week—even just brisk walking—improved the composition of their gut microbiome.

Now that you know how to heal your gut, find out 10 daily habits to improve gut health.