I Quit My Smartphone—And It Changed My Life

Giving up your smartphone can feel like a daunting task, but the benefits can be worth it. Here's why I've felt happier—and healthier—without mine.

Why I Quit My Smartphone

When I got my first smartphone over a decade ago, I loved it. It gave me instant access to my music, a world of information and thousands of photos and videos. But over time, I became increasingly ambivalent about its role in my life. I would repeatedly refresh my email, shop online for stuff I didn’t need and constantly scroll through the latest bad news. I’d often complain to my husband and to my seven-year-old son, Louis, that I felt trapped by it.

So I began to research studies on the mental-health effects of smartphone use. I discovered that smartphones are linked with anxiety, depression and poor sleep quality, especially among younger people. Unsurprisingly, they also impact your ability to parent responsively and to remain in the present moment with your kids.

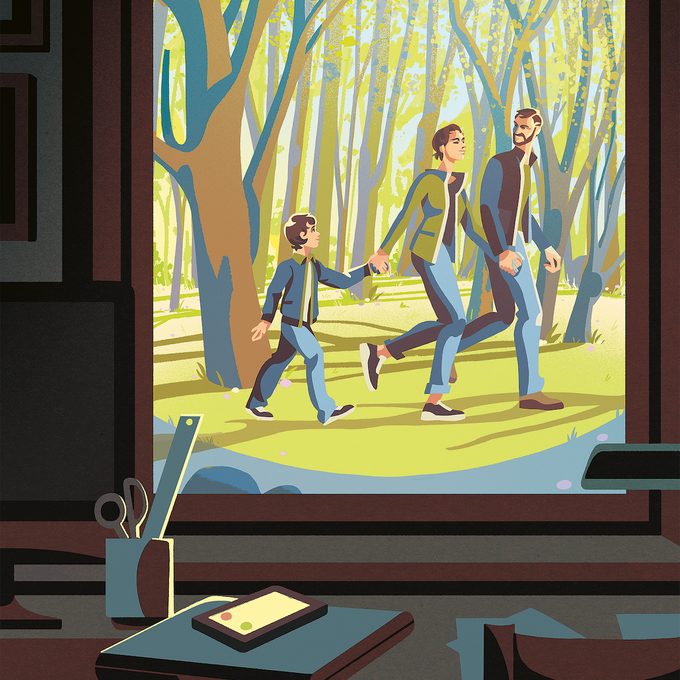

Then, one day last summer, while I was playing with Louis, I was once again distracted by dings and pings. He finally echoed my complaints about my smartphone back to me, but rephrased them as a plea: “Mommy, just give it up already!”

I decided to try. Instead of going cold turkey—no cellphone at all—I bought a flip phone and cell plan for $30 a month. With no touch screen, texting is time-consuming. I can’t access email, music or social media and don’t even try browsing the web without a touch screen. While the adjustment hasn’t always been smooth sailing, it’s easier than I thought it would be and the benefits are worth it.

I’m More Connected in My Relationships

Typing on a flip phone takes forever, and many people expect both quick replies and entire conversations. Early on, while trying to catch up on texts with a friend who had just moved to the Yukon, I finally got frustrated and called her. I realized I hadn’t spoken to her since her big move. It made a difference to hear both the awe in her voice as she described seeing the northern lights and her sadness in being away from an ill parent.

A 2020 study from the University of Texas at Austin found that people prefer text-based communication over using the phone because they fear that the call will be awkward. But, just as I learned, when they were forced to connect voice to voice, they found they felt more bonded to that person.

Benjamin Crudo, CEO of Diff, a Montreal e-commerce agency, told me he gave up his smartphone in 2018 after an off-the-grid honeymoon in New Zealand forced him to do without it. He realized how distracting his phone was during dinners with his wife and others. He’s since had more meaningful interactions with friends—and strangers. “Sometimes,” he says, “I catch the glance of the only other person at an intersection or on transit who is not on a phone and it creates an opportunity for a conversation.”

I Consume News on My Own Terms

About 90 per cent of Canadians are on social media, and 78 per cent say they use it regularly, according to a 2018 Statistics Canada report. More than half of those surveyed use it to stay on top of current events. But keeping up this way has come with a cost. Nearly one-fifth of respondents say their social media habits have resulted in sleep loss, and 14 per cent reported feeling “anxious or depressed, frustrated or angry, or envious of the lives of others.”

Scrolling through the news and gossip served up by my smartphone often kept me tethered to what was trending, whether I actively sought out social media or not. At first, I worried that I would increasingly miss out on the important discussions of the day. That hasn’t been the case. Instead of spending hours sifting through feeds, I use my laptop or tablet to selectively visit a handful of news sources. With the time I save from no longer mindlessly scrolling, I’m reading more books and long magazine articles—and have come to realize that being “in touch” with society does not require constant monitoring of the Internet.

I Shop Less Online

In total, Canadians spent $84.4 billion online in 2020, up from $57.4 billion two years earlier. I’ve done my part to contribute to the increase. During the early pandemic lockdowns, I filled idle time or mini-moments of boredom by browsing the dozen or so stores that send newsletters to my email (something I now check much less often on my desktop). I even found myself repeating lines from department store copywriters—“Maybe now is the time to buy a new winter jacket”—and every time I clicked “buy,” I’d get a dopamine hit.

But now that I’m online about 10 times less, I’m more thoughtful about what I truly need, and I’ve had the time to take up knitting and punch needling—making the hats, bags and scarves I once would’ve “added to cart.”

I’m More Calm—and More Present

Smartphones have become such a big part of people’s lives that when we temporarily can’t find them, it causes a feeling of anxiety or panic that some psychologists have dubbed “nomophobia”—or “no mobile phobia.” Most people feel it mildly, though others can feel it more strongly, depending how tethered they are to their device. When I first quit using mine, I’d still search for it before remembering it wasn’t a part of my life anymore. But just like when I quit smoking, I rode through the withdrawal. Thankfully, it was short-lived.

Wuyou Sui, a post-doctoral fellow researching digital health at the University of Victoria, describes nomophobia as a reliance that’s been placed upon us. Experiencing it isn’t a reflection of anyone’s personal failings, he says: your notifications are meant to form dependence. “Whenever something is designed to make a choice easier, it’s called a behavioural nudge,” he explains, adding that the more central to our lives the smartphone’s functions are, the more tethered we become.

Ultimately, though, that sense of dependence is false. As I’ve found, you can find other ways—with a desktop computer, a printer or, at times, a friend or partner’s phone—to do all the things you need to do. It’s not always convenient, but I know I’m much calmer on a regular basis without my smartphone.

Louis is too young to make that assessment of me, but now when we’re playing and my attention is focused on him, I can see the positive effect in his smiles. And after he’s gone to bed, instead of fixing my gaze on the screen, I light candles, grab a book and enjoy the atmosphere of the room I’m in.

Next, find out how to break up with social media through a 10-step digital detox.