What to Do When a Friend Shares a Conspiracy Theory

Some people still believe the coronavirus is a hoax. Here's expert advice on how to judge information and how to discuss COVID-19 with friends and family.

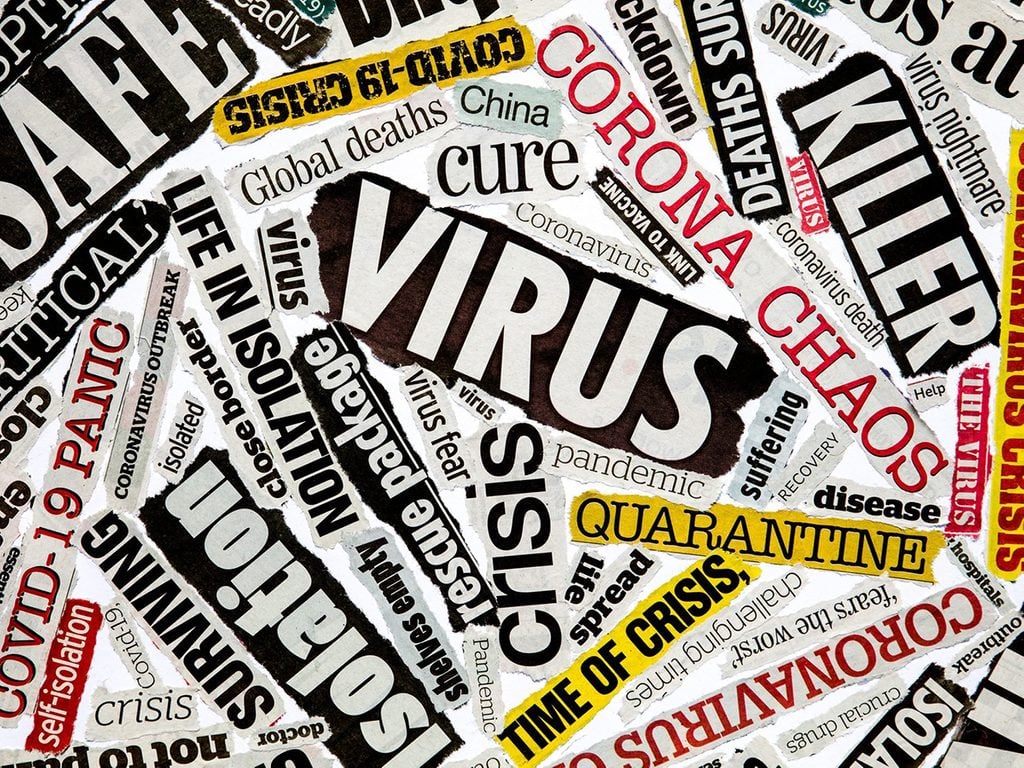

The rise of COVID-19 conspiracy theories

Avoiding pandemic talk with friends and family—virtually or in-person—is sort of impossible. So when a conspiracy video about the vaccine for COVID-19 being a hoax circulated in my family’s group chat, I took a deep breath.

The concerns and stress surrounding the many facets of this pandemic are valid. But how can we tell when information crosses the line into conspiracy theory territory? More so, what’s the best way to respond to loved ones who put their faith in sources that aren’t trustworthy? (Catch up on the latest health news from around the world.)

In my case, I wrote this story and plan to share the link with my family, along with another link to a misinformation-fighting game called Go Viral. (More on this in a bit.)

First off, you should know that you’re not alone in the fight against misinformation—both Facebook and YouTube banned the particular video my family was sharing. You can also use these links to report false information to Facebook’s Help Centre and YouTube’s Help Centre yourself.

Steven Taylor, PhD, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, says this common problem stems from an infodemic, or actually the availability of too much information.

“There’s so much news out there, and for people who tend to get their news from social media, it tends to be distorted,” says Taylor, author of The Psychology of Pandemics: Preparing for the Next Global Outbreak of Infectious Disease. “We’re all faced with the challenge of trying to sort out what is fake and what is true news.”

Why COVID-19 conspiracy theories are booming

One of the reasons conspiracy theories are thriving right now is because it’s a global pandemic—keyword global. Everyone is dealing with the same disease, so a conspiracy theory that originates in Sweden might catch on in Argentina because it’s about the same thing.

There’s a lot more misinformation to go around, notes Jon Roozenbeek, a postdoctoral fellow in the department of psychology at University of Cambridge, in England.

His research focuses on inoculation theory, which explains how a belief can be protected against persuasion or influence in much the same way a body can be protected against disease; for example, through pre-exposure to weakened versions of a stronger, future threat. (Here’s what you need to know about coronavirus in Canada, according to a germ expert.)

Social media

It’s easier than ever for anyone to produce or create content online and for it to go viral anywhere in the world, says Roozenbeek, who co-authored a study published in 2020 in Royal Society Open Science.

His study looked at factors that may or may not predict belief in misinformation about coronavirus. Those factors include social media usage and political extremism, among others.

The study found that people who say they never get COVID-19 information from social media—and instead look to specific sources like major health organizations—appear to be less susceptible to misinformation about the virus than others.

“People who explicitly seek out info from the World Health Organization (WHO) are less susceptible to misinformation,” he says. “People who ignore information from the WHO completely seem to be more likely to believe misinformation about the virus.”

Another finding from Roozenbeek: The more you use social media, the more you believe misinformation about COVID-19.

One possible reason for that? “The more you are exposed to misinformation, the more likely you are to think it’s true,” he says. This is called the “illusory truth effect.”

Plus, the coronavirus is the first major pandemic in the era of social media, Taylor notes. “So people are able to get their voices out.”

The current political climate adds to the perfect storm for conspiracy theorists. In fact, Taylor says conspiracy theorists are getting more attention than ever. (What’s the difference between pandemic and epidemic? These are the COVID-19 terms you need to know.)

The science is evolving

Another pattern is that conspiracy theories flourish in times of high uncertainty. Obviously, the pandemic lends itself to that, particularly in the early stages when so much about the virus was unknown.

Early on, for example, the WHO and other health agencies told people not to wear medical-grade face masks. The official recommendation from multiple organizations was that masks should be saved for healthcare workers, caretakers, and sick people. And it wasn’t clear yet if other kinds of masks offered real protection or a false sense of security.

“They were adamant that we shouldn’t wear masks and that was based on the research back then,” Taylor says. There were also “concerns about there not being enough masks for healthcare workers.”

As more data came in, however, and it became clear that masks helped prevent infections, the guidance changed. Updated recommendations based on emerging science only add fuel to the fire for conspiracy theorists, as they hope to point out mistakes made by public health officials. (Here’s what you need to know about Canada’s three-layer mask guideline.)

It doesn’t help that the new COVID-19 vaccine development program was dubbed “Operation Warp Speed,” says Taylor. “It implies that corners have been cut or that due diligence hasn’t been followed.”

Conspiracy theories as coping mechanisms

Taylor likes to think about conspiracy theories as an extreme form of rumours or improvised news. “Rumours spread when there’s some uncertainty about an important issue, and people are trying to make sense of their world,” he says. It’s a way some people may be coping with this pandemic. (Learn about the benefits of self-care during the pandemic.)

“It’s understandable why people might subscribe to conspiracy theories as a way of making their world seem more meaningful or understandable,” Taylor says.

It boils down to people’s ability to tolerate uncertainty, and there’s a lot of uncertainty surrounding the pandemic. But experts say people should be skeptical about rumors they hear, especially conspiracy theories.

Instead, they suggest relying on authoritative news sources, like the WHO, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Food and Drug Administration, and other major medical and traditional news organizations. (This is what the anti-mask movement needs to know about COVID-19.)

Conspiracy theorists in general are thriving

Hardcore conspiracy theorists tend to be suspicious by nature. If they believe one conspiracy theory, they tend to believe others.

So it’s not surprising to Taylor to see people who are anti-vaccine, anti-mask, and anti-lockdown united together by the same conspiratorial beliefs.

What to do when friends or family share a conspiracy theory

So your aunt, cousin, or Facebook friend shares some questionable piece of information with you about COVID-19 or the vaccine. Maybe it’s a video or a blog post. Now what?

“First, I always want to know the reasons somebody would have sent this to me or what they are trying to push,” says Sharon Nachman, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at Stony Brook Children’s Hospital in Stony Brook, New York. “Then I say, ‘What’s happening in real life and what am I seeing?’ We can only go with what we really see, not with what people are saying they’re seeing.”

How to spot bad information

There’s no automatic way to tell if a video or source is untrustworthy, according to Dr. Nachman. Critical thinking and tough questions might be your best friends.

“When I see something that doesn’t make ‘science sense,’ I know it’s not true,” Dr. Nachman says. For the average Joe without a scientific background, however, it might take a bit more legwork to spot bad information.

According to Dr. Nachman, there are a few things you should ask or know before believing information. If it’s from a medical authority, “I first want to hear what kind of doctor they are, what kind of patients they see, and what their standard practice is,” she says. Is the doctor who is sharing information currently seeing patients? Do they give vaccines?

“Someone that administers no vaccines is potentially an anti-vaxxer, and they are not going to be excited about this vaccine either,” Dr. Nachman says. “So if somebody has a track record of telling you there are no good vaccines, then maybe you shouldn’t be listening to them about this one.”

It’s also important to look at their other credentials and how much experience they have with infectious diseases. (This is what Canadians should know about the new COVID-19 vaccines.)

Remember that this is an ongoing pandemic

“It’s a challenge for everyone because there’s so much research going on and the findings change over time,” Taylor says. “People need to understand two things: The evidence out there can shift over time with research. There are good news sources and not so good news sources.”

This is an evolving situation, and our state of knowledge will change; it doesn’t mean the science is wrong, Taylor says. “It’s a complex issue,” he adds. “And the more we learn about the coronavirus, its transmission, and the vaccine, the more things may change.”

Dr. Nachman agrees. “We recognize in science that we don’t have all the answers, but at least I listen to the question, and I try to figure it out.” Dismissive people who don’t listen to all the questions and answers are likely not trying to figure it out.

“I want to understand what’s the gain for people who are selling COVID-19 conspiracy theories,” adds Dr. Nachman. “Have they worked in a hospital lately and are they actually taking care of sick patients like I am and like all of my colleagues around the country are?” (Read this incredible story of a COVID-19 patients 77-day fight for survival.)

How to talk to family and friends about COVID-19 conspiracy theories

Listen closely

Taylor says there are roughly two kinds of people who entertain conspiracy theories. One is the group that has heard of a particular theory, but isn’t necessarily committed to it. These are the people you could persuade if you present them with information and correct them.

Then there are the hardcore conspiratorial thinkers who already tend to have suspicious minds. Often, they are narcissistic, according to Taylor.

They need to feel special and believe they have special knowledge, but they have regular difficulty telling true from false news.

“So it’s the suspicion, plus that need to feel special that makes them highly invested in adhering to these conspiracy theories,” says Taylor. “It’s difficult to change their minds.”

If you try to persuade them, they may even conclude that you are part of the conspiracy. “If you’ve got a family member who’s of that mindset, the best you can do is agree to disagree with them,” Taylor says. (Learn the right way to handle social distancing rule breakers.)

Have a conversation

Taylor recommends hearing what they have to say and the basis of their concerns first. “You will find some people are anti-vax because there’s a germ of truth to their concerns,” he says. If you listen to their concerns you can then ask them if they know any of the counter-arguments and their opinions on those sorts of things.

“You might even ask them what it would take to change their mind,” Taylor says. So you’re actually setting that person up to think about what is going to change their minds to get them vaccinated.

Another thing to remember: People who share misinformation about the virus don’t necessarily do so out of malice, says Roozenbeek. “They might do it out of a sense of urgency.”

Both Taylor and Roozenbeek suggest avoiding confrontations. Trying to debunk people may make them feel attacked for their views. A threat to their attitudes will likely trigger their defense mechanisms.

Plus, if someone feels under attack, you’re less likely to be persuasive, adds Roozenbeek. (This is why some people are more likely to spread COVID-19 than others.)

Play a game

Roozenbeek and other researchers with the Cambridge Social Decision-Making Lab at University of Cambridge created the game that I mentioned called Go Viral.

“In the game, you’re basically the bad guy, and you go from anonymous social media user to the head of a big conspiracy group on social media,” Roozenbeek explains. You learn how different strategies used in this type of misinformation work and how they become popular.

In a study, co-authored by Roozenbeek and currently under review, participants who played Go Viral became less susceptible to misinformation about the virus for at least a week after playing the game. Try it. Invite friends and family members to play to open them up to new ways of thinking or looking at information about the virus. “That is a nice way to learn about these kinds of strategies and hopefully make people better about spotting them in the future,” he says.

Bottom line

Conspiracy theorists may only believe what they want to believe. And those who give weight to theories they think are true might be well-intentioned. However, everyone should do their own research before passing along information that may not be accurate. Take a look at where the information is coming from, the type of expert who’s sharing the content, and take everything with a grain of salt.

The coronavirus pandemic is ongoing so information is evolving. Turn to reliable sources to stay informed. And don’t believe everything you read or hear.

Next, here are the coronavirus myths you should stop believing.