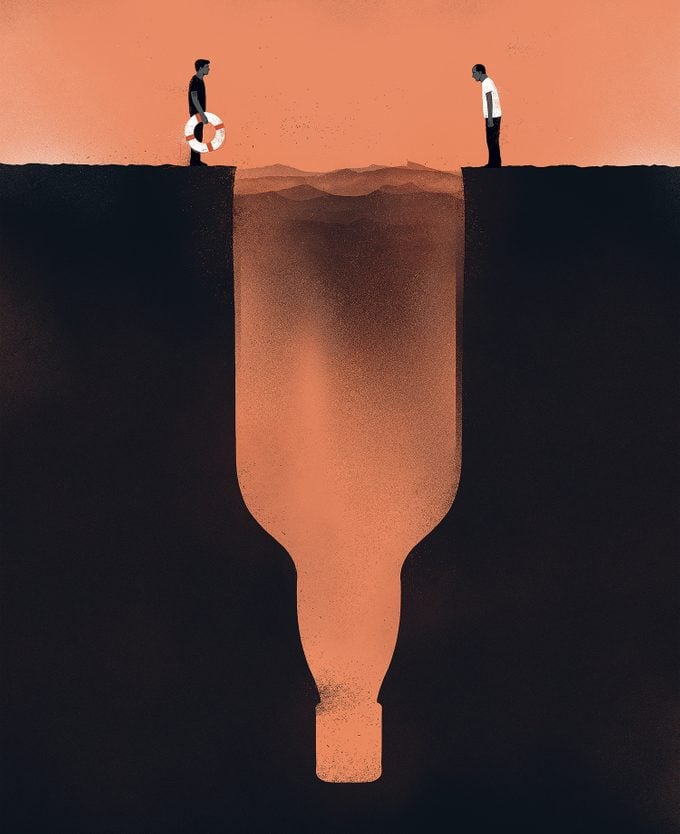

I Helped My Father Get Sober Again. It Saved Our Relationship

I resented the responsibility of getting my father sober—until I realized he just needed me to be there for him.

In May 2013, my father earned his first full year of sobriety in over a decade. To celebrate, he drank again.

I knew this because I had been trying to call him and couldn’t get through. He lived alone in Halifax and normally couldn’t go more than a few hours without calling me to speak of something inconsequential. So when he didn’t answer the phone, I knew. My father was a 68-year-old, thrice-divorced ex-chemist with a penchant for rousing the spirits of everyone around. There was only one thing that could suppress his vitality: himself, drunk.

As in the past, after a few days of not being able to reach him, I got the hint and stopped trying. I was 24 by that point. I had learned not to engage with him when he was drinking, for both our sakes. My steady closeness to his tumultuous recovery during my early adolescence and teenage years gave me an aversion to his relapses as an adult. Anything I ever said when I was upset only added to his list of personal wrongs that made drinking seem right. I’d keep my distance, and he’d keep his drink.

That May, my middling garage-rock band was readying itself for a long tour through Canada and the United States. After a week of zero contact with my father—his binges were lengthy—I looked at my phone during a practice session and saw a series of missed calls from him. Worried, I called him back, and he answered immediately. His voice was shaky and had its often-buried Northern Irish accent, as it always did when he’d been drinking. Over the course of a strained conversation, he confessed that he needed my help. “I’m done now,” he said.

I knew what he was facing. Now that the journey into the depths of his sadness was complete, he had to begin the slow, painful crawl back to sobriety. Within a day, the withdrawal symptoms would kick in. At first, those would be tremors, anxiety, nausea and restlessness. But soon he could experience seizures, dehydration—and possibly even delirium tremens (DTs), which can cause fever and hallucinations.

When he reached this stage, it was crucial that he be admitted to a public detox facility—seizures and DTs coupled with any of the other symptoms can be fatal. In fact, the mortality rate among those who experience this type of withdrawal is five to 25 per cent. Contrary to popular belief, withdrawal symptoms for those addicted to alcohol can be much more severe than those from other drugs—even drugs that are more commonly vilified by society, like heroin or oxycodone. Patients in detox from alcohol need to be closely monitored by medical personnel and, in some cases, may be given medications, often ones from the benzodiazepine family.

Given my father’s age, he was at risk for cardiovascular complications. Many times in the past, his heart had stopped beating, though thankfully only when he was already under medical supervision. This time, however, when my dad called Dartmouth General Hospital, they told him there wasn’t a bed available. He was to call back the next day, and then each day after that, to check again. After a few days of calling the detox facility without any luck, he finally called me.

My dad wasn’t alone in his desperation. According to a count in 2016, Halifax, with its population of over 400,000, only had 16 publicly funded detox beds for adults. With that capacity, some people were waiting anywhere from several days to three to four weeks to receive a bed and treatment. Chris Parsons, the provincial coordinator for the Nova Scotia Health Coalition—a non-partisan public health advocacy group—calls this “woefully inadequate.” For many people trying to get sober, he says, “A five-day wait period is the difference between them deciding they want to turn their life around, or relapsing.”

Meanwhile, across Canada, there have been cuts to already scant public addiction treatment programs. In Montreal, for example, the city’s only free public detox and addiction treatment centre removed 10 of its 28 beds in 2018. And a year later in Ontario, citing a low success rate, the provincial government cut funding for Fresh Start, a program that helped low-income individuals struggling with addiction find employment.

In decisions about where to cut back on health care, Parsons says, certain services are privileged over others. “Things like addiction treatment, mental health treatment and ensuring that you have culturally competent care for immigrant communities are seen as extras,” he says.

Recently, of course, COVID-19 has made everyone more aware of the gaps in our public health system. As the virus spread through our cities and nursing homes, and as many of the most vulnerable have gotten sick and died, it’s become impossible to avoid acknowledging just how thinly our systems are spread after decades of ruthless government austerity.

For example, when it comes to hospital-bed shortages more generally, many Canadians would be surprised to learn that Canada does worse than most other developed countries. According to the World Health Organization, high-income countries have an average of around four to five beds per thousand people. To cite a few examples, Korea has 12.4 beds per thousand people, France has 5.9 and the United States has 2.9. Yet Canada only has 2.5 hospital beds per thousand people; we are consistently at or near the bottom of the list of comparably well-off countries.

In the absence of sufficient public services, family and friends overextend themselves to pick up the slack, playing the role of at-home caregiver out of a sense of obligation to those they love, thinking that if they don’t, no one else will. This may save taxpayers money, but there are untold costs to the people who volunteer, willingly or not, to fill the gaps that are left.

Since 2005, my dad had lived in a one-bedroom apartment within Joseph Howe Manor in Halifax’s south end, a subsidized-housing complex for senior citizens that cost residents a third of their monthly income, whatever that might be, each month. As a kid, I stayed with him during summers, holidays and weekends, sleeping on his fold-out couch in the living room. Most of that time, though, I opted to crash with friends so as to avoid him while he binged.

When I walked in the day he called for help, his television was set to a low, companionable volume in the living room, and he was curled up in his bedroom on a lumpy, sweat-soiled twin mattress with a single sheet over his body. He tried to get out of bed, but he was too weak. I gave him a protein shake, which he’d requested, and put two more cases of it in his refrigerator.

Being helpful to my dad in this way wasn’t always my approach. As a teen, after years of having to keep his recovery attempts a secret from everyone, including my mother—and so not being able to get any support from others—I became resentful of that burden. I cursed his name at any instance of a relapse and would abandon him for days on end. He’d sit alone, sorry and ashamed, until he finally felt strong enough to call on an old friend for help.

My distancing tact—called “tough love,” both colloquially and officially in the field of addiction—is practised by many, even if they don’t know its origins. The concept was first touted in Al-Anon, the support group for loved ones of alcoholics founded in 1951 by Lois Wilson, the wife of the man who co-founded Alcoholics Anonymous. Then, in 1982, Phyllis York, a family therapist, brought it to the masses in her bestselling book Toughlove, which urged readers not to bail out their children if they were arrested, and to cut off contact if they relapsed.

Never officially schooled in the ways of tough love, I came to it naturally, thinking that denying him compassion might be a form of punishment he would learn from. Or other times, I felt I had earned the right to express the anger I’d long withheld, regardless of how it made him feel. But in the end, none of it made me feel better and none of it helped him. Instead, when I withheld my love and compassion, he had little reason to hold back on drinking himself into further oblivion.

After entering my 20s and gaining distance from my dad’s drinking, I began to understand that it wasn’t necessary for me to reprimand him when he drank. I could just be there for him, or check in on him, without scolding him and exacerbating his feelings of failure and worthlessness that accompanied his binges. In other words, I could care without putting myself in harm’s way.

Surveying my dad’s apartment that day in 2013, I saw empty beer cans strewn throughout the living room, as well as several empty bottles of Listerine, which he’d turn to when he was out of alcohol. I wanted him to know that I wasn’t there to make him feel bad about another failed recovery, so I cleaned his apartment as best as I could. My standards for cleanliness back then didn’t go much higher than his, but I’m sure he saw me, out of the corner of his eye, sweeping dust and bottle caps into a chip bag, and felt my love for him. After chatting with him for a bit, I went back to my friend’s recording studio to get ready for the tour, which was less than a week away.

The next day, my dad called again. With an even shakier voice, he asked if I could go to a pharmacy and buy him Gravol, which helped curb his nausea, vomiting and motion sickness. When I arrived with it, he was on the couch, facing the back cushion, as though he were giving his television set the silent treatment. He immediately took three of the pills with a glass of water. “Hope I don’t just throw these up,” he said. I hoped so, too.

As the days passed, I became increasingly worried that a bed in detox wouldn’t become available before something terrible happened. I worried that he was having seizures when I wasn’t there. I worried his heart might stop. I worried I would be out of town when he died.

My lack of expertise in treating a substance-use disorder wasn’t the only reason it was a bad idea for me to help my father with his recovery. He wrestled with the guilt and shame of being nursed through withdrawals by me, his son, as I had to also play the role of therapist to him—a situation that only exacerbated the depressive thought patterns precipitating his relapses.

When a dearth of government support thrusts the onus of around-the-clock care onto someone’s family and community, we would like to think that those people respond with finesse. But they’d need resources for that, such as outpatient treatment programs, safe-injection sites, cognitive behavioural therapy or medications that diminish cravings, like naltrexone.

Of course, some families can afford to send their loved ones to for-profit facilities, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars. But also, I’ve seen and heard many stories about low-income individuals finding ways to pay the exorbitant treatment costs, either by selling belongings, taking out mortgages, liquidating their savings or sinking into unfathomable debt. Families in this situation can create the sort of environment that makes it even more difficult to thrive in the future.

“Say you get out of rehab and it turns out your brother sold his truck to pay for your treatment,” Chris Parsons says. “That guilt weighs on you and impacts your ability to maintain your sobriety.”

In situations like mine, where a private centre was out of the question, a person shouldn’t be forced to choose whether they look out for themselves or help a family member through detox. No untrained and heartbroken family member should be left to carry that weight when they lack the resources they’d need to do it properly.

To my relief, on the morning I left for New York, the first stop on my band’s tour, my dad finally received word that there was a bed for him in the detox ward. In total, he had waited five days, longer than most waits he’d ever had to endure. By that point, he’d already passed through much of the disease’s long night, as I thought of it, but the hospital saw to it that he received the care needed to get through the rest.

After seven days in detox, he returned home. I was on the road, but he told me over the phone that he’d never felt as cared for during a withdrawal as he had in the week before finally getting that bed. I’d only provided him with the most basic comforts—food, conversation and constant check-ins—but he said it was more than he had received in years. He told me that when he entered detox, it was with less dreariness than ever before because I’d made him feel that his worth wasn’t based on his sobriety.

Like most stories of recovery, it didn’t end there. Even after the relapse in question, my father relapsed twice more before he passed away from a brain tumour in 2017. Through all that, I came to understand that this back and forth was just the rhythm of his condition.

I feel lucky that I didn’t make a rash decision to cut my dad out of my life for good, and that I came around to treating him with the love and compassion he deserved, sober or not. As imperfect as they were, I wouldn’t have wanted to miss out on the last few years I had left to share with him.

Next, find out what one mother learned after her daughter came out as trans.

© 2020, Maisonneuve. From “Labour of Love,” By Ryan David Allen, Maisonneuve (August 25, 2020). maisonneuve.org