My Late Mother’s Fur Coat is Horrifying—But I Can’t Bring Myself to Throw It Out

As I opened a garbage bag and got ready to stuff it inside, I noticed something...

My mother died when I was 23, some 18 years ago now, but it wasn’t until being stuck at home during a pandemic that I finally went through the boxes of her things that sat piled in the corner of our basement. In them, I found a glass vase that was easy to give away and a scrapbook of the royals she made in the 1970s (an homage to her teenage crush on Prince Charles) that was easy to sandwich between two hardcovers on my bookshelf. Then there was her fur coat, her disgustingly glamorous fur coat. It’s gorgeous. And horrifying.

As I ran my hand over the soft, brown mink fur, I wondered whether I should keep it simply because it belonged to her, even though I would never wear it. Like many women these days, I’m anti-fur. I’ve even signed petitions calling out companies for using real animal fur in their winter coats when, in my view, they could just as easily make them with faux fur. I avidly follow Esther the Wonder Pig—a 600-pound pet that two Ontarians have made Internet-famous to promote veganism and, along with my twin six-year-old sons, volunteer at their Happily Ever Esther Farm Sanctuary in Campbellville, Ontario, where we shovel manure.

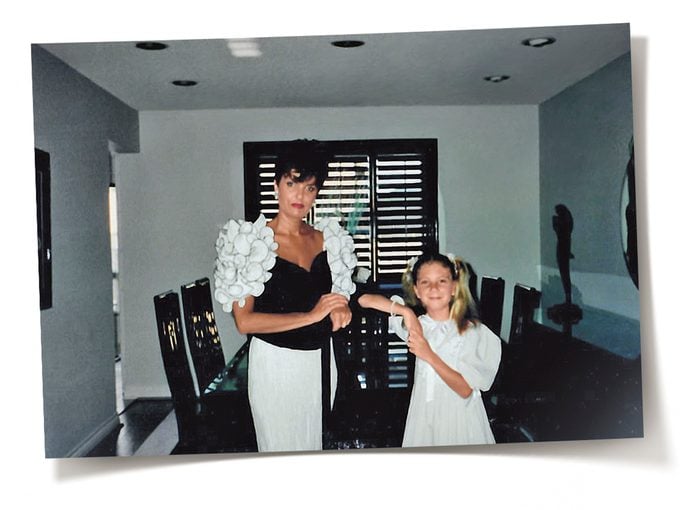

If my mother were alive today, she would also never wear fur. While she was drawn to high fashion—in the boxes I also have dozens of pairs of her high heels—she was progressive in her politics. And yet, although I never witnessed it, she obviously did go out in fur at some point. As I picked up one of the coat’s heavy sleeves and inhaled its thick scent, I could imagine her as a young woman, dressed up for the theatre, complete with her tinkly earrings and red lipstick. I could see her date slipping the coat off her slender shoulders as she commanded the room with her laugh.

My mother was a lot like a fur coat: elegant, stately, at times controversial. Just about all of her jokes and iconic one-liners were “not safe for work.” I, on the other hand, am short, have never worn lipstick and don’t like attention. When I was a teenager, my mother would encourage me to have parties at our house. Why didn’t I invite the whole school over to our place, she wondered? Didn’t I want to be the life of the party?

I really didn’t, but I also didn’t want to admit that to her. “What are you going to do when there are people smoking here?” I replied to avoid answering the question.

“I’ll ask for one.”

I know she meant well, but sometimes it felt like she didn’t see me, or didn’t understand that I didn’t have to be like her. Those of us who knew my mother all gravitated to her and orbited around her, but she made me feel as if I was never orbiting the right way. To her, my clothes were boring, my hair too curly, and my disposition overly anxious. I never felt worthy of being her daughter.

There was one exception, however, a personality trait we shared equally, and that was our ability to keep a sense of humour during difficult times. A month after my mother was diagnosed with terminal adrenal cancer, my two older brothers and I took her to a play—a last night out before she was to have surgery. In the bathroom before the performance, I heard her giggling in the stall next to me. When she came out, I asked her what was so funny.

“I put toilet paper down on the seat, like I might catch something!” We howled with laughter.

And as I tried to figure out what to do with my dead mother’s fur coat, I couldn’t help having some fun with it first. I slipped my arms through the sleeves and posed while my husband snapped pictures. (Look at me! I’m wearing a fancy fur coat!) Then I draped it around my cockapoo, Diego, because with his dark curls he looked just like the Games of Thrones character Jon Snow. After snapping some photos of the Lord Canine Commander, I was finally ready to part with the coat. But as I opened a garbage bag and got ready to stuff it inside, I noticed something. The coat fell open and there on the inside pocket her name was embroidered, all lovely swoops and curves stitched along the grey silk lining. I ran my fingers along the “P” and “L” of Patti Litner and stopped. Tracing the letters, I could suddenly see a softer version of my mother, perhaps a part of her on the inside that I never got to know.

I had hoped while my mother was dying that we would put our different personalities aside for our final months together. I imagined us whispering secrets to one another, holding each other’s hands in the quiet moments. I pictured her pulling a specially chosen book from her bookshelf and placing it firmly in my hand. “I want you to have this,” she’d say. I would open the book and there would be a handwritten message to me on the cover page making it clear that she saw me not as she wanted me to be, but just as I am.

Instead, we argued as we always did, about all the things we had always argued about—small tiffs about my bent posture as I sat at her bedside, and bigger fights where I tried to convince her to follow the doctor’s orders and she would refuse. At the end of it all, she never gave me anything special or important. I was saddled instead with all the stuff she left behind.

And there I was in the basement, 17 years later, still as insecure and uncertain as ever. I could no longer bring myself to get rid of the coat because, if I did, all that would be left of my mother is me. I am not as glamorous as this fur coat, and I thought perhaps it’s a better representation of her, a better legacy.

I put the coat on a hanger and squeezed it between my sons’ snow pants. Eventually I know I will get rid of it, because I am my mother’s daughter after all. And now that I’m a parent, I’ve seen my wit, pragmatism and strong sense of justice reflected in how my boys regard me. I know somewhere inside, there’s a part of me that is as strong and decisive as my mother was. One day I will hear her voice say to me, “Why on earth are you holding on to that silly fur coat? I never even liked it that much!”

“I don’t know,” I’ll say, dumping it in the trash. “I don’t like it either.”

Next, read the powerful story of how one man forged a stronger bond with his father through email.