Broken Phone? Holey Clothes? Why You Should Fix It, Not Throw It Away

A "fix it" revolution is leading everyday people to take things into their own hands and divert material from landfills with DIY.

Flora Collingwood-Norris was playing with her new puppy, Stitch, while wearing a favourite second-hand find: a coral cashmere sweater. Stitch, an excitable black poodle mix, jumped up and grabbed her sleeve—and tore several holes in it with her sharp teeth.

Collingwood-Norris, now 37, wasn’t about to toss the item out. “I can’t bear to throw away nice clothing just because of a hole,” she explains. As a knitwear designer based in Galashiels, Scotland, she was used to making her own sweaters, but after she was left with a handful that had Stitch-inflicted holes, she decided to tackle a new skill: mending. She began by reading a book called Make Do and Mend, about the innovative thriftiness that emerged during World War II.

Instead of trying to make the repair as small as possible, she turned to “visible mending,” a trend in repairing clothes that leaves an intentionally obvious fix. Sewers add flowers, bright plaid squares or other small designs to damaged clothes. “Every time you do a repair, it’s like having a new garment in your wardrobe,” says Collingwood-Norris.

She’s even started to repair other things—including a hole in the upholstery of the wide red sofa chair she’s sitting on during our video interview.

Sadly, we have become accustomed to replacing things instead of repairing them—and the garbage is piling up. Worldwide, we toss out 92 million tonnes of textiles every year. Electronic waste is another growing problem: An estimated 50 million tonnes of it is created each year around the world. In Canada, e-waste has more than tripled in the last 20 years, reaching nearly one million tonnes in 2020.

Why not fix it?

The good news is that fixing things can help solve the waste problem. It’s part of a larger shift toward a circular economy—the idea that instead of tossing out items once they are broken or out of date, we reuse, repair or refurbish them, keeping them out of the landfill for as long as possible.

Approximately one-third of greenhouse gas emissions come from manufactured goods and consumables. According to a 2023 report from Circle Economy, a Netherlands-based NGO, if the world switched to a circular economy, we could lower the amount of material we need to extract from nature by a third.

Here’s how governments, grassroots organizations and everyday people are taking things into their own hands.

A “fix it” movement

While mending clothing is a skill anyone can learn, repairing things like cellphones and appliances isn’t so easy. In fact, some products are made in a way that prevents consumers from doing so. Companies such as Apple and Samsung have even been fined for “planned obsolescence”—designing products that break easily or become outdated quickly, forcing consumers to buy new ones or purchase upgrades.

But a global “right to repair” movement is pushing back against our disposable culture. Consumers want to be able to fix what they’ve bought—to reduce their environmental footprint, to save money or just on principle.

Governments are also playing a role in shifting corporations from a use-it-and-replace-it business model to one that’s more repair-friendly. In March, the European Commission adopted a right-to-repair directive, demanding, among other things, that companies sell replacement parts for five to 10 years after their products are sold.

Right-to-repair legislation has now been led in more than half of the U.S. states; Australia passed a motor vehicle right-to-repair law; India has proposed a framework for mobile phones, tablets, cars and farming equipment; and Canada has a proposed bill to amend a copyright law that restricts access to necessary repair information.

Legislative measures like these both follow and fuel the public’s desire to repair, says Ricardo Cepeda Marquez, technical lead for Waste and Water for C40, a global network that helps cities fight climate change. “Repairing is a great opportunity to become aware of our collective consumption and the urgent need to reduce waste.”

Online repair manuals

There was a time when people fixed things themselves or called their local repair shop. But as more items were manufactured overseas and prices dropped, replacing even a big purchase like an appliance became more convenient than repairing it.

That’s changing, in part due to information now available online. The popular how-to site iFixit.com has facilitated more than 100 million repairs.

iFixit began in the early 2000s, after its co-founder and CEO, California-based Kyle Wiens, dropped his Apple laptop, breaking it. He discovered there were no repair instructions available. With help from his classmate and iFixit co-founder Luke Soules, Wiens, who had spent his childhood taking apart radios and appliances with his grandfather, managed to fix his computer through trial and error. He and Soules wrote a manual based on that experience and posted it to a website they created called iFixit.com.

Twenty years later, iFixit has grown into a database with nearly 100,000 repair manuals for everything from electronics to clothing to appliances. And its mission has gone mainstream.

“We’re now seeing manufacturers show interest in making it possible for users to repair things,” says Elizabeth Chamberlain, director of sustainability for iFixit. Companies like Google, Microsoft, Samsung, Motorola, HP, Patagonia and the North Face are selling official parts and sharing their repair guides through iFixit.

“We have this vision of a world where repair is the expectation for all things that are made,” says Chamberlain.

Repair cafés

The first Repair Café opened in 2009 in Amsterdam, offering in-person fix-it help. The volunteer-run network now has more than 2,700 locations—including in Canada, Belgium, Germany, France, India, Japan, the U.K. and the U.S. Organizers set up events, and volunteers with repair knowledge bring their toolboxes, 3-D printers, sewing machines and bookbinding equipment to places like libraries and community centres. They will try to fix whatever people bring in, for free, and teach visitors how to do repairs themselves.

“It is a very social event, with lots of discussions about what is being fixed, and about the whole idea of repair,” says Paul Magder, the co-founder of a Repair Café in Toronto, adding that he thinks a big draw is the sense of community. Magder, who has been organizing Repair Café events for a decade, has seen the demand for repairs and the number of volunteers steadily growing.

While interest among all age groups is on the rise, there is a shortage of repairers in their 20s and 30s. “Repairing requires skills that younger people don’t have, simply because they lack experience,” says Christophe Gatt, president of Repair Cafés Paris. “This is why we try to share our knowledge.” In late 2022, the group launched the first Repair Café for children ages five and up, with workshop themes such as tools, soldering and sewing.

In addition to going home with a coffee maker or toaster that’s working again, visitors to Repair Cafés leave with a better understanding of how things function, says Gatt. “And when we understand how something works, we use it better. We ‘consume’ in a more responsible way.”

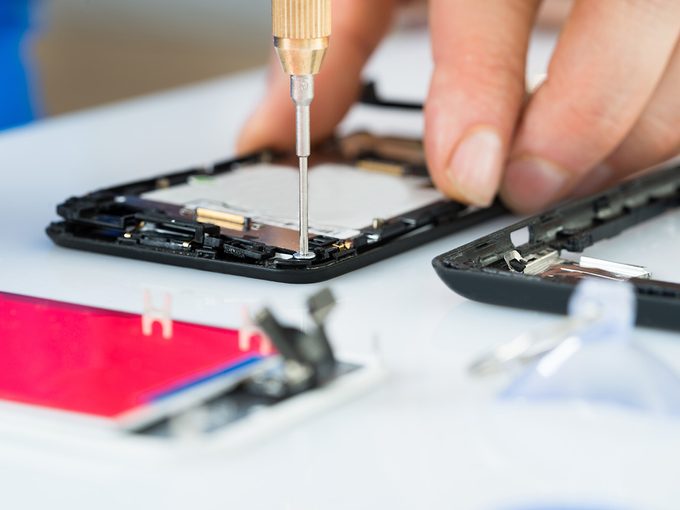

Fixable cellphones

Cellphones are one of the most discarded electronic items. That’s why Fairphone tried to disrupt the industry starting in 2013. The Dutch social enterprise wanted to show that it was possible to produce an ethical smartphone that could be repaired.

Their smartphones sell for €579 ($850) across most of Europe. Customers can fix their own phones with replacement parts—such as cameras, batteries and speakers—purchased from the company’s website. Installation guides are readily available, and the only tool required is a small precision screwdriver (the kind used for glasses or watch repairs).

Some larger companies are now following Fairphone’s lead. In March, Finnish telecom company Nokia released the G22, a smartphone designed to be easily repairable at home. It sells for less than $240, with repair parts starting at $32 (it’s currently only available in Europe and Australia.) Since the phones can be disassembled, they’re easier to recycle; materials like batteries, which can’t be recycled, can be separated from components like metal cases.

Last year, technology giant Apple introduced self-service repair options. Customers who want to fix their own device can go online to rent a repair kit, check out repair manuals and buy the part they need, be it a new screen, battery or camera lens. And to help facilitate DIY repairs, newer smartphone models, like the iPhone 14, are designed to be easier to open than previous models.

Soon all smartphones might have longer lives: Once approved, the EU’s right-to-repair directive will include a mandate that batteries be easier to remove and replace.

Responsible fashion

A few decades ago, “fast fashion” came into vogue, encouraging consumers to keep up with changing trends by offering cheaper clothes. It has been disastrous for the environment. A whopping three-fifths of clothing ends up in a landfill or incinerator within a year of production. Plus, clothing production requires a lot of water—it can take 7,500 litres to make a pair of jeans, for example.

Responding is “slow fashion,” which celebrates high-quality handmade clothes created locally. As well, more consumers are choosing to buy “preloved” clothing via social media groups, consumer websites or vintage stores.

And, like Flora Collingwood-Norris, people are increasingly mending their own clothing so it lasts longer.

The coral sweater her dog Stitch tore into was patched with bright polkadots, and the elbows were mended with circular sunsets and flying-bird silhouettes. The sweater has become part of an exhibit at a museum in Devon, U.K., about clothing repair throughout history to the modern day.

Collingwood-Norris now runs mending classes on Zoom for people around the world. She also shares advice with her 100,000+ Instagram followers, and published a book, Visible Creative Mending for Knitwear, in 2021.

She’s happy that repairing one’s own clothes is becoming popular once again.

“It sort of skipped a couple of generations, but it’s really exciting to see it coming back,” she says. “It gives me optimism for the future that there is a willingness to change and reassess habits.”

Next, check out these energy-saving tips to save you money this season.