While browsing through an art volume in a bookshop one day in 1998, 70-year-old Georges Jorisch came across a sketch of his great-aunt. Suddenly, his mind was flooded with a wave of memories-among them, the Gustav Klimt paint-ings that had hung on the walls of his childhood home. A Montrealer with roots in Austria, where some of his relatives had died in the Holocaust, Georges decided to take the first steps toward recuperating the precious artworks stolen from his family by the Nazis.

His first queries to the Austrian government were typed and sent by post. Usually, there was no response. “No one in our family initially believed that his quest would lead anywhere,” says Georges’s grand-daughter, Édith Jorisch. “My grandfather often told us about growing up in an extremely cultured environment, about all the personalities who passed through. My grandmother Eliane was less than impressed. ‘That’s all fine and dandy,’ she would say, ‘but in the meantime, we’re having potatoes for dinner.'”

Édith, 23, is a filmmaker who has collected her grandfather’s stories for a documentary. “For a long time, he was a mysterious character,” she says. “It’s only in these last few years that I’ve grown close to him.” Prior to her film project, she’d known that Georges had been forced to leave school because of the war. She’d also known that he had immigrated to Montreal in 1957 with his Belgian wife and their first two children, and that he’d worked in a factory before becoming a photog-raphy-equipment salesman-a position he held for 22 years. But she was unaware of the breadth of struggles he’d overcome.

Born between the two world wars in 1928, Georges grew up in a prominent Jewish family in central Europe. His was a progressive clan of strong women, scientists and intellectuals. Édith describes the time her grandfather met Sigmund Freud: “You seem like a good little boy,” said the father of psychoanalysis, mussing young Georges’s hair. Georges’s great-uncle, the steel magnate Viktor Zuckerkandl, had purchased several paintings from Klimt and, in 1903, commissioned the modernist architect Josef Hoffmann to build an art nouveau-style sanatorium in Purkersdorf, a suburb of Vienna. More than just a medical centre, the building, with its clean lines, was an homage to the aesthetics of the new century. When Zuckerkandl died childless in 1927, his monuments and artwork were distributed among his surviving siblings-including Amalie Redlich, Georges’s grandmother.

After his parents separated in 1933, Georges and his mother, Mathilde, moved with his grandmother to one of the villas next to the sanatorium, while his father, Louis Jorisch, stayed in Vienna. Georges was sickly as a child and wasn’t allowed to venture far from the house.

“For a long time, we thought the villa had been demolished. That’s what my grandfather told us,” says Édith. “But I found it on Google Maps, and I was able to visit this past summer. I saw the bay window my grand-father was always talking about, next to where the Klimt paintings he was searching for used to hang.”

On March 14, 1938, at the age of 10, Georges spotted German planes in the sky above his home. He later saw Adolf Hitler ride triumphantly down the streets of Vienna, surrounded by his troops. Hitler gave the fascist salute, and the crowd cried, “One people, one nation, one Führer!” as he passed.

With Austria now annexed by Germany, Louis Jorisch called his wife. “We have to leave right away,” he said. “Put our son in the car and meet me in Vienna.” Mathilde was convinced things would soon settle down and refused to leave her dia-betic mother behind. Louis fought his wife for custody of their son.

“The judge happened to be one of Louis’s friends,” says Édith. “In his ruling, he said, ‘Hitler wants all Jews out of Austria, so the child can leave with his father.'”

In March 1939, equipped with forged passports, Georges and his father boarded a train to Cologne, Germany. From there they crossed the border into the Netherlands before finally making it to Brussels, where they would stay for the duration of the war. As for Georges’s mother and grandmother, in 1941 they were loaded onto a train bound for the Lodz ghetto in Poland, a trip they didn’t survive.

By 1942, Georges and his father were constantly relocating from one address to another to avoid detection. Georges was suffering from malnutrition and a lack of exercise. By the time the war ended, his legs had atrophied so badly that he hurt himself dashing across the street. It would take him a year to heal.

“Another consequence of the war,” says Édith, “is that my grandfather wouldn’t be able to finish his education and would live a very modest life, financially speaking.”

Upon returning to Austria, father and son tried to recuperate the goods Mathilde and her mother had packed away. The sanatorium had been occupied first by the Germans and then by the Russians after they liberated the area. The containers had been pillaged, and everything was gone.

Four years before dying of a heart attack, Louis requested an investigation into the whereabouts of his lost property. The resulting police report would be invaluable to his descendants.

By 2007, Georges believed he’d found one of the paintings stolen by the Nazis. It had been years since he’d begun his search, but here finally was Klimt’s Blooming Meadow in the collection of Leonard Lauder, heir to the Estée Lauder cosmetic empire. According to Klimt’s catalogue raisonné, the piece had once belonged to Amalie Redlich, Georges’s grandmother. Armed with this information, Georges filed a lawsuit against the New York billionaire, whose lawyers fought it vehemently. Georges eventually had to withdraw his claim because he lacked proof.

Undeterred by this roadblock, he went on hunting for two landscape paintings of Lake Garda in northern Italy. Near the end of 2007, he gained the help of Ruth Pleyer, an Austrian expert in art provenance. According to her findings, Klimt had produced only three paintings of the Lake Garda region. The first was burned, and the second didn’t actually show the lake. The third depicted a church overlooking one of the lakeshores in Cassone, Italy, but this piece hadn’t been seen in a long time.

It took Pleyer two years to find Church in Cassone. The owner lived in Graz, Austria. He had inherited the painting from his father, who hadn’t known about the painting’s history when he’d bought it in the 1960s, and he had no intention of giving it up. Nor was he obliged to do so. In Austria, the law protects collectors who purchase pieces in good faith from legitimate art dealers. Within a year, though, the man from Graz had a change of heart. And in the meantime, Pleyer happened upon the police report from 1945, proving the painting had been stolen.

According to Édith, Church in Cassone became the first painting ever to be restored to the descendants of Holocaust victims from an Austrian private collector. Georges put it up for auction in February 2010 in London, England, agreeing to split the proceeds evenly with the Graz collector. Georges and Édith listened to the bidding over the Internet. Sotheby’s had estimated the work’s value at $20 to $30 million. It sold for $43.2 million.

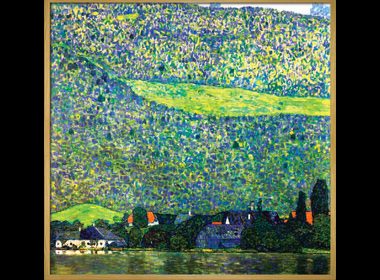

The next piece on Georges’s list featured a landscape with a stream. Thanks to Pleyer’s research, he discovered it was Lake Attersee and not Lake Garda as he’d always believed. He also learned that the damaged painting was one of the most popular pieces at the Salzburg Museum of Modern Art. After considering Georges’s request, the Austrian authorities declared that “the conditions for the return of the painting have been fulfilled,” and the museum agreed to return it. To show his gratitude, Georges financed the restoration of one of the museum’s wings (a donation of 1.3 million euros, or $1.8 million). The wing now bears the name of his grandmother.

Litzlberg on Attersee was sold on November 2, 2011, at Sotheby’s in New York. Just like the Lake Garda painting, it had been stolen by an Austrian named Freidrich Welz, one of the biggest art dealers of the Nazi regime. This time, Édith at-tended the auction to film her grand-father’s reaction when he laid eyes on the piece for the first time in 73 years. After a heated bidding war, the painting went for US$40.5 million, but Georges seemed impervious to the frenzy. “He wasn’t a demonstrative man,” Édith explains. When an Irish journalist asked him how he was feeling, he re-sponded with a simple “good.” To a German television reporter, though, he spoke of “the accomplishment of a lifetime.”

Georges still had one painting left to find. Children on Their Way Home From School, by Austrian painter Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller, depicted a boy and girl in an Alpine landscape. Georges found it in South Africa and purchased it with the intention of donating it to Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts. “It’s one of the only luxuries he allowed himself after receiving millions of dollars in restitutions,” says Édith. “Throughout his quest, he was never motivated by money. But he wanted to express his gratitude to Quebec for welcoming him and his wife when they arrived in 1957.”

Georges wasn’t able to attend the museum’s ceremony last spring to celebrate the painting’s arrival. He died suddenly on September 25, 2012, at the age of 84. He had spent more than a decade tracking down his family’s heirlooms. Perhaps Georges was leaving behind a glimpse of himself with Children on Their Way Home From School. It’s easy to see a parallel between the two determined pupils in the portrait and the little Jewish boy forced into hiding to survive. But Georges had always refused to rue his past or feel sorry for himself. “He looked ahead instead,” says Édith. “That’s why he succeeded. His determination was an example to me, and I’m proud of him.”