Exploring the Rich History of Montreal

Montreal celebrates its 375th anniversary this year, and the city’s festivities and exhibitions are paying particular attention to its diverse neighbourhoods and communities. This prompted me to hit the pavement, armed with a camera, to explore that diversity. I began by asking myself what precisely the anniversary commemorates. What happened back in 1642? The answer: A privately funded religious enterprise founded a mission on Iroquois territory.

A century earlier, in 1535, French explorer Jacques Cartier had visited the northeastern region of the New World, declaring it a possession of the king of France. Cartier encountered the Hochelaga settlement on an island now known as Montreal, but it was no longer permanently inhabited in 1642. The Iroquois nation used it as their hunting grounds and it was a dense forest. This did not, however, prevent the Société de Notre-Dame de Montreal pour la conversion des Sauvages de la Nouvelle-France from buying the island as private property. Under the society’s auspices, Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve, Jeanne Mance and about 40 people founded the Ville-Marie mission in May 1642 at what is now called Pointe-a-Callière. Their goal was to evangelize the First Nations peoples and form a society devoted to God. The colonists built a fort to guard against frequent attacks from the Iroquois, and several of the new arrivals somehow managed to survive those first difficult years.

Some 11 years later, dozens of new colonists joined the other French settlers. Among them was a young Marguerite Bourgeoys, who felt called to teach the children of Nouvelle France. She established a school and found patrons to build the island’s first stone chapel, Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours. The vestiges of this chapel lie under the present-day chapel at the east end of the Old Port.

This seemed like a good place to start my explorations. These days, the Old Port looks like one big tourist attraction, but it features the chapel at one end and the Pointe-à-Callière museum, built above archeological remains of some of the earliest buildings, at the other. At the Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours Chapel, you can visit the crypt and the ongoing archeological dig under the building.

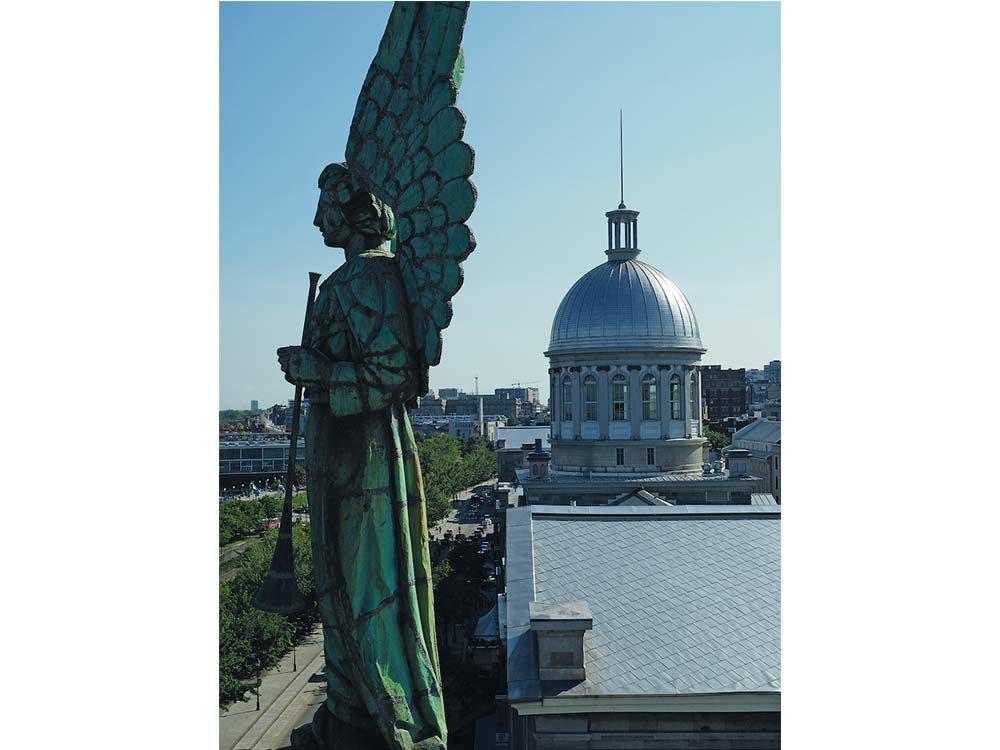

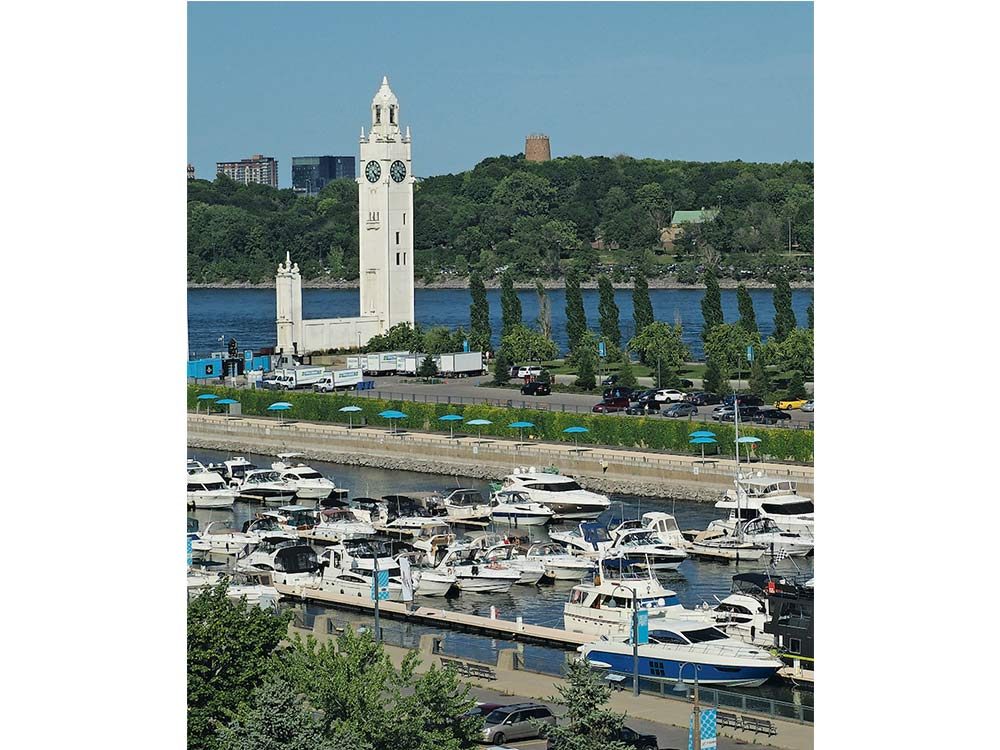

Climbing its tower brings you closer to the angels adorning the roof. It also offers a view of the port and river to the south, the Jacques Cartier Bridge to the east, and the downtown core to the west, slightly obscured by the dome of the neighbouring Bonsecours Market. The Old Port offers an abundance of leisure activities, such as climbing, zip lining, quadricycling, paddle- boating and—new this year—riding a Ferris wheel.

Leaving the modern-day cacophony of a summer’s day in the Old Port in search of more history, I found myself in Pointe-Saint-Charles for a visit to Maison Saint-Gabriel. This house was at the heart of a working farm run by Bourgeoys and her women’s religious congregation: the Congrégation de Notre Dame. Here, she also provided shelter and education to the newly arrived Filles du Roi, preparing them for a life in Nouvelle France. These young ladies would become wives and mothers to the new inhabitants of Montreal. A guided tour of the house offers a glimpse of life in those early days, while the grounds provide an unexpected oasis of tranquillity.

In Bourgeoys’ time, Pointe-Saint-Charles was agricultural land belonging to the Sulpician order. Fast-forward 200 years, and Canada was under British rule. The Lachine Canal had been completed, and the area had numerous industries and major construction work in progress, including railways and the Victoria Bridge. This brought many labourers to “the Pointe,” among them French-Canadians but also Irish, English and Scottish immigrants. They were later joined by Poles, Ukrainians and Lithuanians. The Sulpicians sold the land, which soon was covered in two-storey duplexes to house the newcomers.

The Irish left their stamp on Pointe-Saint-Charles, with street names like St. Patrick, Place Dublin and des Irlandais. The Black Rock monument, on an access road leading to the Victoria Bridge, is dedicated to the 6,000 Irish immigrants who lost their lives in 1847 to typhus contracted aboard ships as they immigrated. Most are buried nearby. As I watched cars go by it, I wondered how many motorists understood its solemn significance.

After the Lachine Canal closed to navigation in 1970 and industry dried up, the neighbourhood fell into decline. With the re-opening of the canal in 2002, however, gentrification began. Bicycle paths and lovely parks make it even more attractive to visitors now.

Pointe-Saint-Charles is a prime example of how Montreal’s history is inextricably tied to the waves of migrants seeking a new life in the New World, beginning with those intrepid French missionaries and continuing with a more diverse population. To get a better idea of how different groups have helped shape the city, you need only stroll up St. Laurent Boulevard.

Maryse Loranger explores the original industrial hub of Montreal.

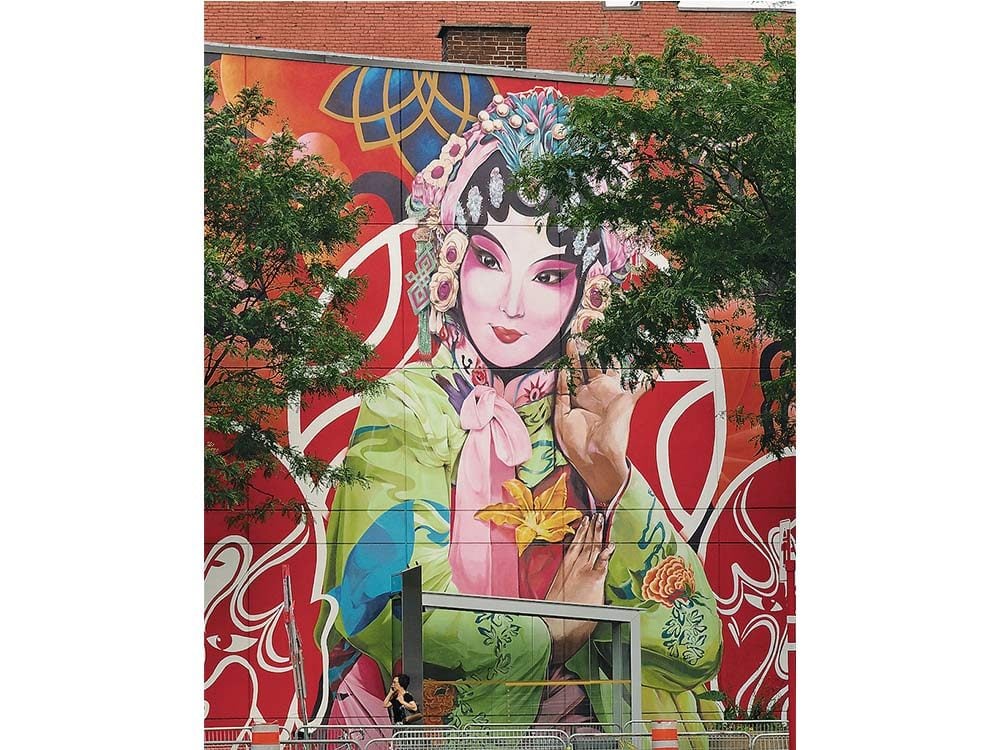

Above Viger Street, you pass under Paifang gates to enter Chinatown. When I visited in the summer of 2016, the gates were shrouded in scaffolding, no doubt being refurbished for 2017’s celebrations. The Montreal Chinese Hospital, the Montreal Chinese School, the Chinese Catholic Mission, and the Montreal Chinese Community and Cultural Centre are all located here. Most striking are the numerous shops and restaurants bustling with activity well into the evening. On De la Gauchetière Street, a summer sidewalk sale draws a large crowd.

Chinatown’s northern gate leads to the Quartier des Spectacles, a block to the west. In the summer months, this usually means there is one festival or another going on, including the Montreal International Jazz Festival, the Festival Juste Pour Rire (Just for Laughs) or the Festival Nuits d’Afrique. My goal that day, however, was to reach the Quartier Portugais (Little Portugal) in Le Plateau, all the while noting how much the diverse ethnic communities formed a tapestry, their influences and colours meshing into one another.

Check out 54,000 Portraits: One Photographer Captures the Many Faces of Canada!

I passed Schwartz’s Deli along the way, a Jewish restaurant famous for its smoked meat, which inspires fierce loyalty in its ethnically diverse patrons. Even the waiters come from all backgrounds. At lunchtime, customers line up out the door, and inside tables are shared.

At Rachel Street, a small detour two blocks to the west, is Mission Santa Cruz, a Portuguese Catholic church, which is brightly decorated every August 15 to celebrate the Assumption of Mary. Back on St. Laurent at Marie-Anne Street, there’s a Portuguese quincaillerie (hardware store) and Parc du Portugal across the street.

Continuing up St. Laurent, I reached Mile End, where many of Montreal’s first Jewish migrants settled. Distinct Montreal-style bagels—far superior to New York–style bagels!—are baked here at two iconic spots, Fairmount Bagel and St. Viateur Bagel.

Here are 10 Must-Try Canadian Dishes (and Where to Find Them).

Farther north, opposite St. Zotique Street, the Parc de la Petite-Italie announces arrival in Little Italy. Heading east on Dante Street towards the church of the Notre-Dame-de-la-Défense, there’s another quincaillerie— this one Italian—featuring a dazzling assortment of coffeemakers and cooking utensils. The Romanesque-style church is large and stately, and features a fresco above the altar in which Benito Mussolini appears on a horse. This raises questions about the divergent loyalties some Italian-Canadians may have felt before and during the war.

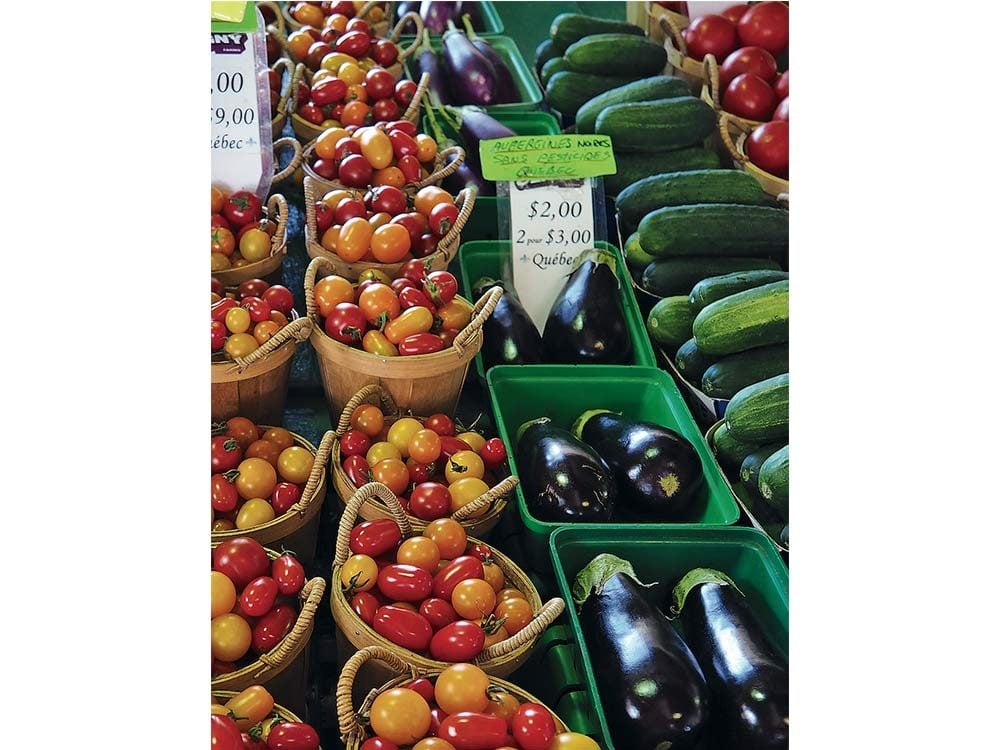

Not far from the church is one of Montreal’s oldest markets still in operation, the Marché Jean-Talon. Built in 1933, it is a mecca for today’s foodies. In the summer, farmers offer up their fruit and vegetables in mouth-watering displays under the protective roof. Cheese, meat, fish, baked goods and exotic treats are also to be had in this bustling marketplace.

While I was taking pictures of assorted storefronts on St. Laurent Boulevard, the owner of Bar Sportivo invited me inside. He offered me a cup of coffee and told me about how he, a proud Italian-Canadian, had worked side-by-side with his wife, a French-Canadian, for so many years until her death a few years ago. As I left the café, another patron walked out with me and told me how he had come here from Trinidad and Tobago. It struck me once again that most of Montreal’s citizens have roots elsewhere. Although for French-Canadians like me the roots in France feel remote in time, the very reason we are celebrating 375 years is because a few intrepid French undertook the perilous adventure of a beginning a new life here. Moreover, they survived and persisted.

The brief impressions of the various neighbourhoods mentioned here do not do full justice to their fascinating stories, nor have I been able to include many other communities of equal interest in this space. However, I hope this provides some incentive for visitors and residents alike to seek out new and unfamiliar neighbourhoods, meet their people and learn their stories.

Check out 13 Reasons It’s Great To Live in Canada!