A few summers ago, on a visit to my hometown of Montreal, I stood on the observation deck of the Pointe à Callière museum looking down towards the Old Port on the left. On the right, I could see an expanse of green punctuated by an immense silo fallen into disuse. Although the silo was a familiar landmark, the area surrounding it was unknown territory to me. Vaguely, I could remember visiting the 2003 Mosaïcultures Internationales de Montréal at that location, but I had not been there since then.

The Jardin des Écluses, the green oasis that had piqued my curiosity, was developed and landscaped in 1992, a few years after I had moved away from the city. Exploring the park firsthand made it onto my list of things to do when next in town.

On a fine summer day in 2015, I put that plan into action. Deciding it best to start at the western edge of the park and make my way back to the Old Port, I exited the subway at Place Bonaventure station and walked towards the water. For a Montrealer with the skewed sense of direction that comes from the notion that the island lies in a east-west position, it felt like I was heading south, but a quick look at the map revealed I was actually heading east. There aren’t many stores or cafés in this part of town, and it wasn’t until I reached Wellington Street that I found a place to meet my caffeine needs.

Beyond Wellington street, things started to look deserted. The western-bound railway tracks coming from Bonaventure Station rise above street level, their concrete structure forming the illusion of a border between two different lands. I crossed over to the other side via a small street that saw little traffic. The first body of water I came across was the Peel Basin, a big open space at the head of the Lachine Canal. It was eerily quiet, almost empty. I did spot a few people using the cycling path, one man struggling with his fishing tackle, a couple of men in the distance already fishing and a woman power-walking on the quay. But other than that, there was virtually no human activity to be seen, only the concrete evidence of past activity. A century ago, this would have been one of the busiest shipping routes in Canada.

Across the Peel Basin, I had a clear view of the iconic Farine Five Roses sign atop the former flour mill. Many Montrealers feel a warm attachment to this neon sign. It almost disappeared in 2006 when the brand was sold to Smucker’s, but public outcry saved this testimony to Montreal’s industrial roots. In the past, with all the factories cluttering up the landscape, this was no doubt a rather ugly part of town. In the present day, as the clouds cast playful shadows on this landmark mill, the scene takes on a certain beauty.

The elevated Bonaventure Expressway crosses the Peel Basin leading into downtown Montreal. It hinders the view of the mill as you approach it on the footpath and creates a no man’s land at its base. The city is in the process of tearing down the elevated highway and converting it into a boulevard to revitalize the area. Having passed under the highway to reach Rue de la Commune, I looked back and saw that despite its concrete mass, it had an elegant design typical of ’60s modernism. Its sweeping curve over the water seemed to cry out optimism for a bright future: Look how far we’ve come and where we are going!

The Jardin des Écluses-loosely translated, this means Garden of Locks-begins at this point. Farther down de la Commune Street, pedestrians can cross the canal over the lock gates to access the green park area. These locks allowed ships to pass from the Lachine Canal into the Old Port and the St. Lawrence River. As cargo ships grew in size, the locks became too narrow and were closed in 1970 when a new maritime route opened on the south shore of the river. The locks were refurbished beginning in 1990; in 1996, the area was designated a National Historic Site, and in 2002, the Lachine Canal and its locks were reopened to pleasure boats.

The canal splits into two branches before spilling into the river. The Jardin des Écluses is thus divided into three strips. Crossing over a lock gate, I reached the middle strip of green with spare, elegant landscaping. On that weekday afternoon, I saw only one pleasure boat pass through the locks and very few people in the park itself. It is hard to imagine this once was a busy industrial centre.

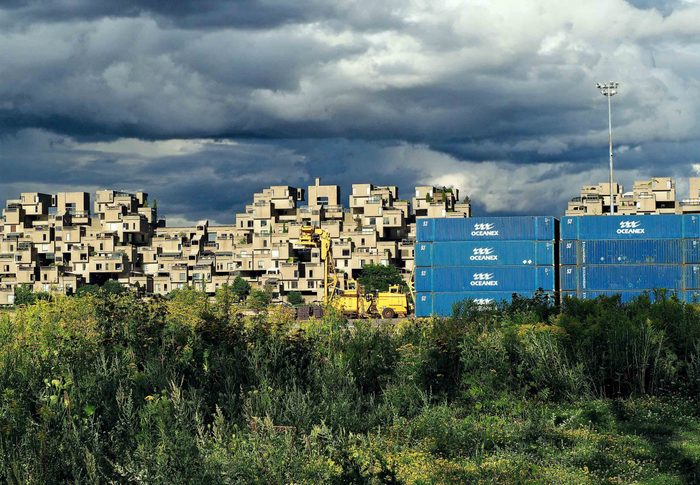

Silo No. 5, no longer in use, still stands as a striking monument of that industrial past. It looms large at Pointe du Moulin beyond the official edge of the park. A path runs along the fenced-off silo. I marvelled at the graffiti adorning its upper right corner, not so much for the artistic merit as for the improbability of anyone reaching that spot. Farther down the path, an opening in the fence allowed for train rails to pass onto Pointe du Moulin. No sign indicated that it was forbidden to cross the rails, so I did and then followed a clear path to a set of stairs down to the water’s edge. In front of me lay Alexandria Quay, and to the right, I was surprised to see Habitat 67 closer than expected and partially obscured by containers on another quay.

Standing there admiring the mix of industry, modern architecture, unruly plant growth at my feet and fast-moving water, Silo No. 5 looming large behind, I grew uneasy: This could well be the most deserted spot in the city. An attacker could emerge from that tall grass, throw my body in the water and no one would ever know what had happened to me. It seemed prudent to turn back up to the main path. Upon reaching that path, I had to dodge an oddly shaped amphibious vehicle full of happy tourists heading down to the water. What a relief! They certainly would have spotted me at the water’s edge along with any would-be attacker. It wasn’t the most deserted spot in Montreal after all.

Perhaps the park attracts larger crowds on weekends, but on that day it struck me as a quiet, forgotten place. Except for that one moment of unease, or should I say silly panic, I appreciated the emptiness of that large open space. That very unease could very well be a symptom of living in densely populated urban environments. We no longer feel comfortable in empty spaces – all the more reason for cities to conserve such places and allow residents to rediscover the pleasure of standing alone in the wide open.