The Canadian Indigenous experience

A large portion of my 30-year career as an artist has been devoted to revealing the truth behind Indigenous communities. I admit to changing my style a little over the years, but I like to define my work as a continued study of the northern Canadian Indigenous experience. It is my way of politely and respectfully communicating the harsh realities of poverty, living within a hegemonic society, and rethinking what “reconciliation” is and if one can really ever achieve such.

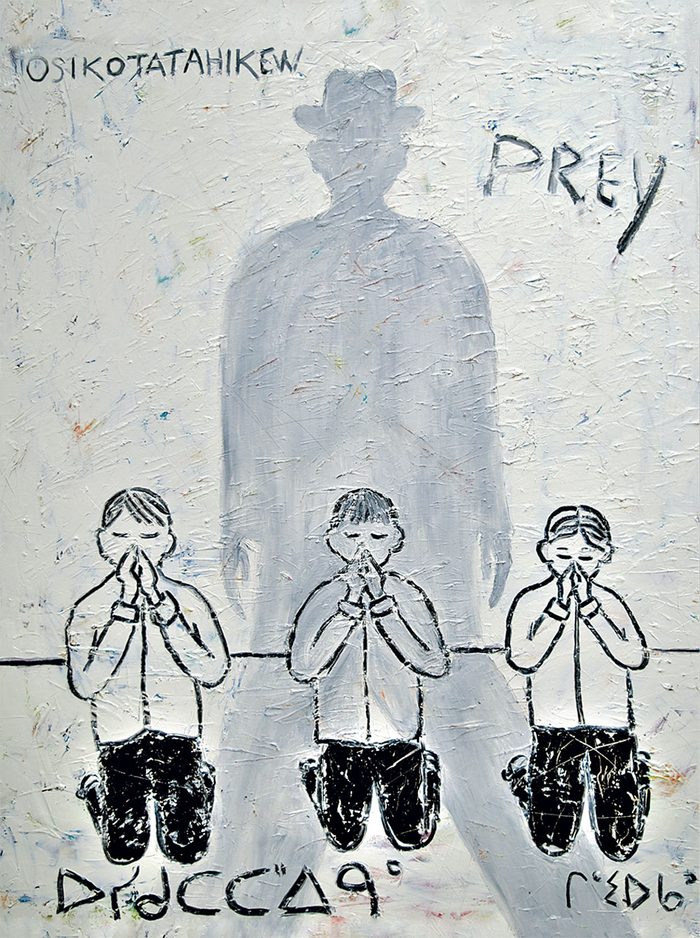

As it stands, I don’t think the word “reconciliation” was meant for us. It was directed, more so, to the dominant culture, so that non-Indigenous Canadians could become aware of the injustices our people endure everyday. I am not convinced that Canada can actually reconcile, nor do I believe we can forget and feel whole in our current relationship with Canada.

It is not quaint and peaceful in a typical northern Indigenous community; it is quite the opposite. There is violence, drug and alcohol addiction, gas and solvent abuse, and a lot of frightening sexual and physical harm. I have painted about these negative realities a lot during my career. Being 63 years old, I seem to have grown tired of it all. I even find myself trying to forget about it. Issues of health, poverty, housing, gangs and crime have taken over many northern Indigenous communities, while our old cultural values of hope, honesty, hard work, respect and honour struggle to remain. Having lived through these difficult environments has made painting them that much more of a challenge. There have been times where I’ve taken breaks and worked in other styles, but regardless of how physically and emotionally draining it is, my heart tells me to continue.

What reconciliation really means

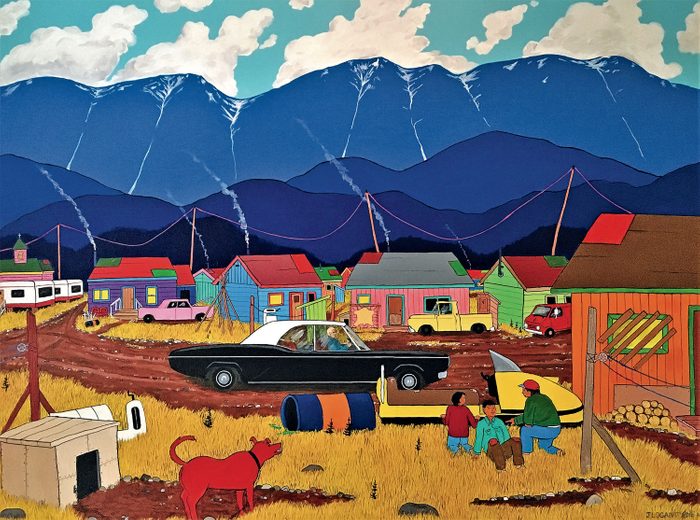

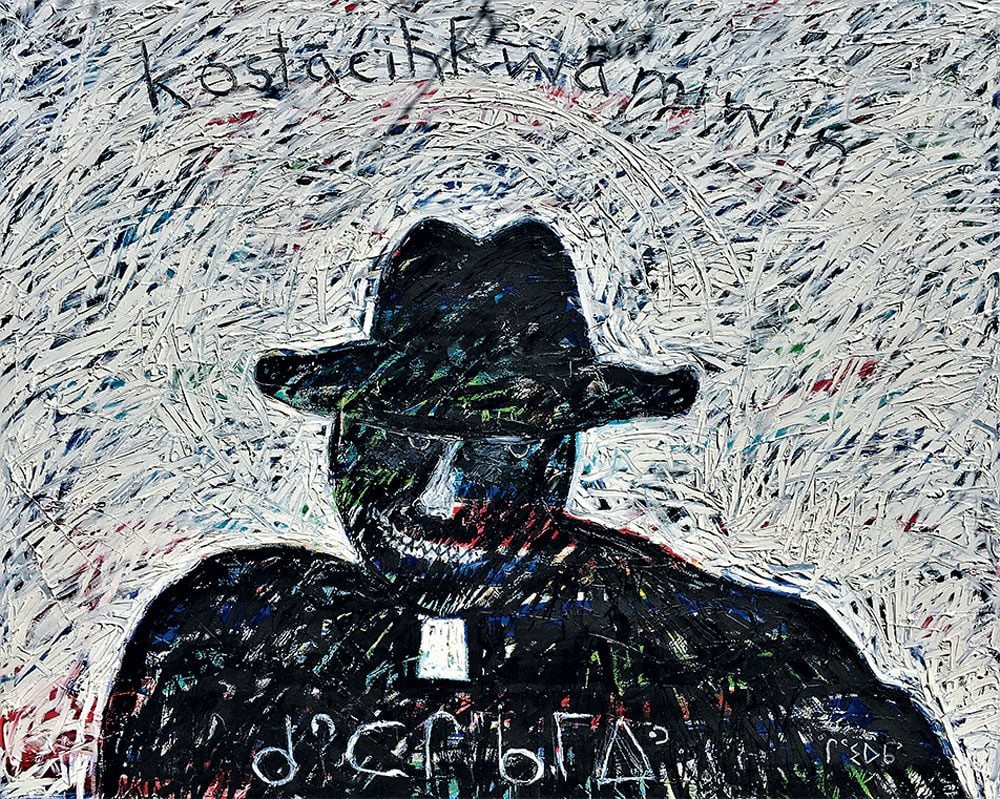

Throughout my most recent “Village” works, I have intentionally left subtle hints depicting the harsh living conditions in certain Indigenous communities I’ve lived in or otherwise became familiar with between 1960 and 1990. In my “Reconciliation” series, I delve deeper into my past experiences as a child, how I pushed through them and how I was reawaken during my time in the Yukon.

I imagine it being very difficult for non-Indigenous Canadians to really grasp what reconciliation means for us. I have always done my best to communicate the complexity of our communities through my art—but unless you have truly immersed yourself within Indigenous groups, it’ll be difficult to understand. There is so much pessimism surrounding Canada’s Indigenous communities, and it mostly emanates from people who do not know the history and do not understand the spiritualism of place or the need for resistance.

Here’s how the Indigenous art of mukluk-making brings cultures together.

Finding beauty in everything

Indigenous people must resist in order to remain culturally significant. Assimilation is not the answer. Many of our people feel we live under “occupation,” similar in some ways to what happened to the people of German-occupied Europe during the Second World War. One big difference is that we’ve been living under a form of occupation for much longer than that. It has been going on since 1876, when the Indian Act stripped us of our freedom.

As an artist, my intentions are never to focus solely on political matters. I simply want to record the pathos of living under the hegemonic condition we find ourselves in today.

During my lifetime, I have been impoverished, I’ve felt lost, and I have experienced abuse. However, I always enjoy looking at the glass as half full, rather than half empty. There is beauty in everything—you just have to find it. Perhaps that is why I sometimes paint in bright colours and, other times, in black and white. Sometimes an artist does not fully understand or cannot explain the reasons behind the works he or she creates; it’s up to the viewer to interpret what is depicted and then come up with an answer on their own.

Learn about the woman working with First Nations elders to preserve Canada’s plants.

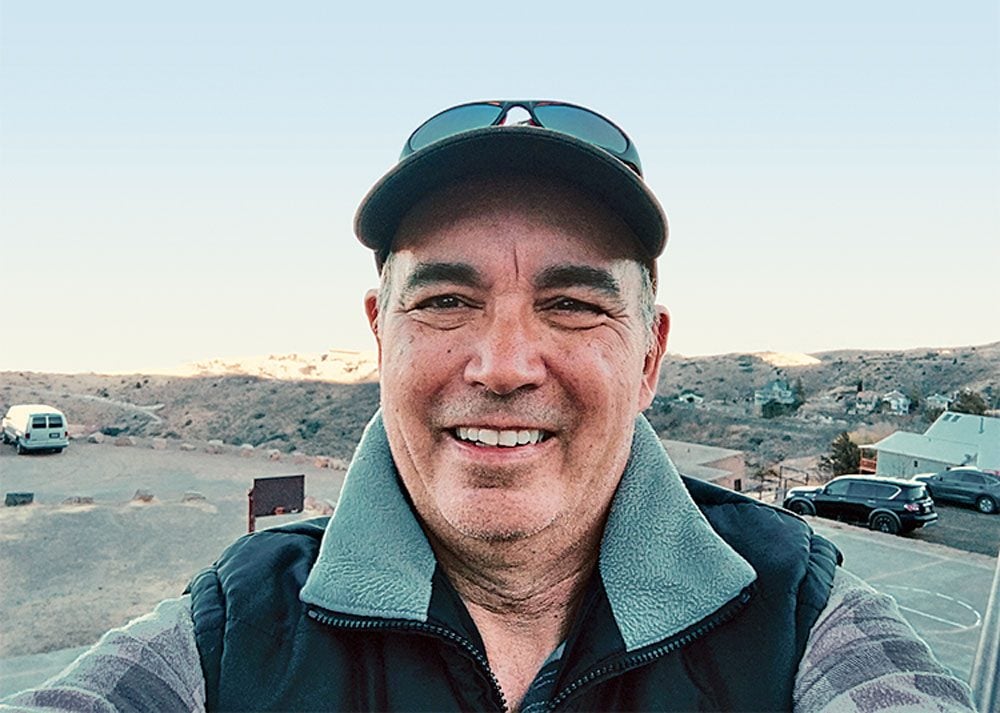

About artist Jim Logan

Both of Jim’s parents originally lived in Alberta but moved to British Columbia to find employment. Jim was born in 1955 in New Westminster, B.C., and grew up in a Métis household in Port Coquitlam, B.C. He studied at the Kootenay School of Art in Nelson, B.C., and spent a number of years working as a lay minister in the First Nations village of Kwanlin Dün, near Whitehorse. While there, Jim’s life and art career were transformed as he first began painting social-statement pieces based on his observations and personal experiences.

Through his work, he advocates for the restoration of identity and self-awareness within First Nations communities. Jim sheds light on the low visibility of Aboriginal aesthetics in formal art history and has managed to bring a new significance—a Native perspective—to the icons of Western art. His approach allows him to question what he believes to be the “hegemonic” nature of our society, in which European dominance prevails, not just here in North America, but around the globe.

Since 1984, he has exhibited his works in a number of venues, including the Bearclaw Gallery in Edmonton, the Dalhousie Gallery in Halifax, the Gallery Phillip in Toronto and the Yukon Arts Centre in Whitehorse. His style takes a varied and unique approach to the depiction of the Native way of life.

In 1988-89, Jim became the co-founder and president of the Society of Yukon Artists of Native Ancestry (SYANA). In the span of one year (1991- 92), his work was featured in four films and videos across Canada. And most notably, he became the founding member and chief of the Eastern Aboriginal Artist Collective in 1999. From 1999 to 2002, Jim was the Aboriginal arts curator for the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, in Halifax. That same year, he moved on to become a visual arts program officer at the Canada Council for the Arts in downtown Ottawa.

Next, check out the compelling paintings of Blackfoot artist Kalum Teke Dan.