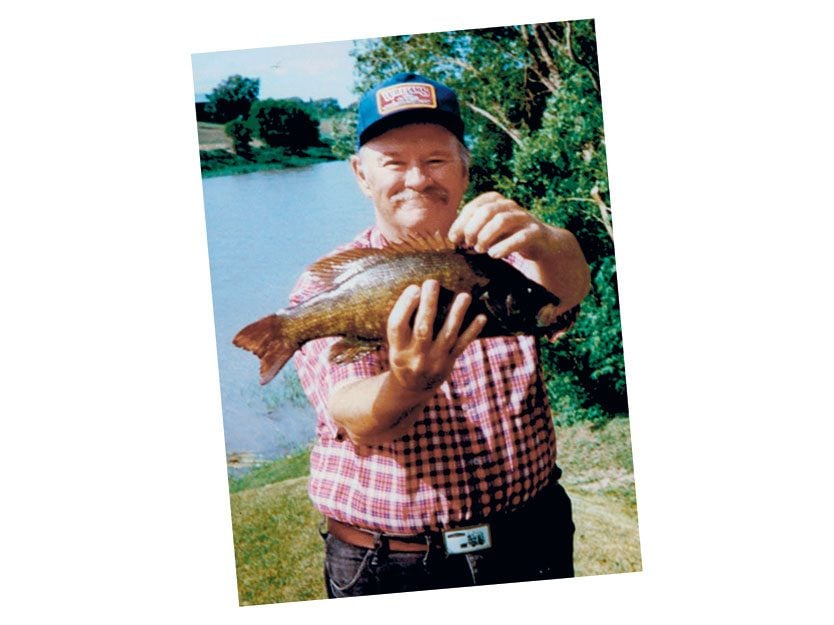

Meet Eric McComber, a Mohawk Fisherman

It’s late January and “high winter” has arrived on the frozen wastes of Lake St. Louis, the thermometer registers ten below Fahrenheit and the wailing wind rolling across the miles of windswept ice makes it seem like the high Arctic. A solitary figure dressed in a bulky camouflage suit moves swiftly as he pulls his nets through a large cut in the two-foot-thick ice. The nets are laden with fat perch and other pan fish; as fast as he folds them into the large fibreglass tub on the sleigh behind his snowmobile, the nets and fish are both almost instantly frozen into one heavy ice mass. The fisherman’s name is Eric McComber, a proud member of the Mohawks of Kahnawake, located on the south shore of the Saint Lawrence River, across from Montreal. He’s keeping alive the ancient tradition that has been practiced by his people for untold generations.

Eric is a big man, with not an ounce of fat on his powerful physique, and it’s not hard to tell that he’s in a trade that requires lots of muscle power. But even muscles are not immune to bone-chilling cold, and Eric decides that he’s had enough for today. There’s one more net to check, but it will have to wait until tomorrow. He knows that it’s just too dangerous to continue any longer. As Eric says, “There’s a line I just won’t cross. If I think my life is in danger, I back off and that’s that.”

But danger doesn’t always announce itself before arriving and sometimes a dangerous situation can arise almost without warning. When you’re a commercial fisherman, you’re out on the water and ice all year round, and danger lurks around every turn. In early winter, the thickness of the ice must be gauged carefully and caution observed, if you don’t want to go for a sudden frosty dunking. As the winter progresses, danger comes in the form of hypothermia, sudden squalls and total whiteouts where visibility is reduced to zero in a matter of seconds.

In spring, summer and fall, Eric nets sturgeon in the territorial waters of Kahnawake, which stretch all the way from below the Lachine rapids upstream into Lake St. Louis, around Saint Nicholas Island and beyond; these waters are not for the novice or faint of heart. When you fish below the Mercier Bridge, your first mistake could very well be the last mistake you’ll ever make! The rock and boulder strewn waters of the Lachine Rapids are just minutes away downstream, and beckon loudly to vessels in distress. No matter how well you know the channels, currents, rocks and eddies (and Eric knows them as well as anybody in Kahnawake), everything is subject to change. The river literally transforms itself from year to year. Every spring after the ice goes out, huge boulders of a ton or more can be moved hundreds of feet or further downstream from their last location, where they lie silently in wait for unsuspecting fishermen. In these waters, if you break a shear pin or lose a prop, it can mean your death.

Eric tells me that some of his best fishing spots are in the very fast currents where the water swirls and cascades wildly, washing food up for the large schools of foraging sturgeon. When you’re netting in fast water it can be dangerous, but that’s where the sturgeon are and that’s where you have to fish for them. An average day’s work for Eric starts around 8 a.m. and, depending on how big the catch is, can sometimes end long after midnight.

How Eric Became a Fisherman

Eric, like many other Kahnawake Mohawks, worked in high steel structures for many years. From 1979 until 1998, he worked in New York, Detroit and many other U.S. cities. The pay was great, but you were hardly ever home and there was very little family life. At the time, Eric had six kids at home whom he loved dearly and he felt that he just wasn’t spending enough time with his family. So, in 1998, he made what was the biggest personal decision of his whole life, he quit high steel and took up commercial fishing as a full-time business. He had always loved the water and the outdoors; his father, Jimmy, had taught Eric everything he knew about the river and all the different varieties of fish when Eric was growing up. So he started out fishing. He knew pretty well where to find perch and walleye, so that was no problem. In the beginning, he did quite well netting for perch and walleye, but the income wasn’t really enough to live on, and then one day while out netting for walleye, he discovered a major spawning area for sturgeon. Now everything had come together! He made himself some new nets specifically for sturgeon and soon was making some very respectable catches. Now, with the walleye, perch and sturgeon, he had the nucleus of a successful business and McComber Fisheries was born.

Eric and his employees now produce fresh and smoked sturgeon, walleye and perch fillets, and fresh and smoked wild Atlantic salmon from the Mi’kmaq of Restigouche. Eric says one of his long-term goals is to open either a fish market or a seafood restaurant on the reserve. McComber Fisheries now employs up to ten people full-time, which helps to create employment in Kahnawake. To keep the tradition of a Native fishery alive on the reserve, Eric is now teaching one of his cousins and a nephew all the tricks of the trade, and some of his own boys will be coming into the business as well.

Eric lives and breathes fishing. The name of his third son, when translated from Mohawk, means “he hunts fish.” The name of his fourth son when translated means “sturgeon” and the name of his fifth son when translated means “in the fast water.”

Eric is married to Paula and the couple have five sons and two daughters. He says that to him his family is everything. He is now 57 years of age and hopes to fish for another 25 or 30 years. If anybody can do it, I really believe he can. Eric says that he is proud to be preserving his heritage and sometimes he says he can hear his ancestors calling out to him in approval.

Apart from fishing, Eric’s greatest passions are lacrosse, hunting ducks and geese, and being in the marshes in the fall.

Eric loves the water, the outdoors and his work, saying, “It’s a dangerous and tough job, but when you’re in the great outdoors, you’ve got to love it.”

Don’t miss this gallery of Canadians enjoying the outdoors in winter.

Hooked on Fishing

My own fishing adventures began a bit over 60 years ago on the Chateauguay River, when my mom and dad rented a summer camp on the farm of Donald Fiskin, near Howick, Que. The river flowed right by his land and he had three rowboats for use by his guests. I was just a kid and when I told Mr. Fiskin that I would like to try fishing, he lent me a rod, gave me and my parents a lecture on life jackets and boat safety, and pointed to a spot about half a mile upstream, where an old tree was sticking out of the water. “Try there; it’s a good spot,” he said, and told us where to find some worms. It took Dad about half an hour to row up to the tree. We tied up to an out-thrust limb, and it wasn’t long before I had my first bite, and what a bite it was—the fish just about tore the rod out of my hands! I hung on for dear life and tried to reel it in as it headed downstream at breakneck speed. Dad hurriedly untied the boat and started to row as fast as possible so we could stay near the fish. After about 20 minutes, it started to tire and I managed to get it close enough to the boat for Dad to grab the line and haul it in. Later we found out it was a smallmouth bass and weighed over four pounds. Dad rowed back to the old tree and tied up again. I baited up and threw the line overboard and, to my amazement, I immediately had another hard bite. After a thrilling tug-of-war that lasted four or five minutes, I managed to land (with Dad’s help) a beautiful walleye of about three pounds. I baited up again and before the sinker hit bottom I had another spirited fight on my hands, hauling in a four-pound pike. Dad said, “Let’s head home and ask Mr. Fiskin how to clean them so we can fry them up for supper.” I readily agreed and, from that day onwards, I was hooked on fishing.

Next up, Our Canada contributor Gary Graham fondly recalls what it was like fishing with gramps.