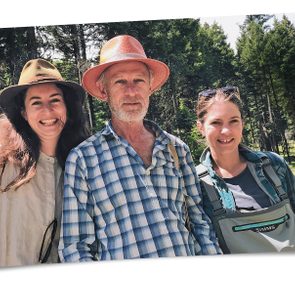

My Father, My Hero

Honouring the legendary Wilf Hiebert: Blacksmith and welder.

There was no one like him

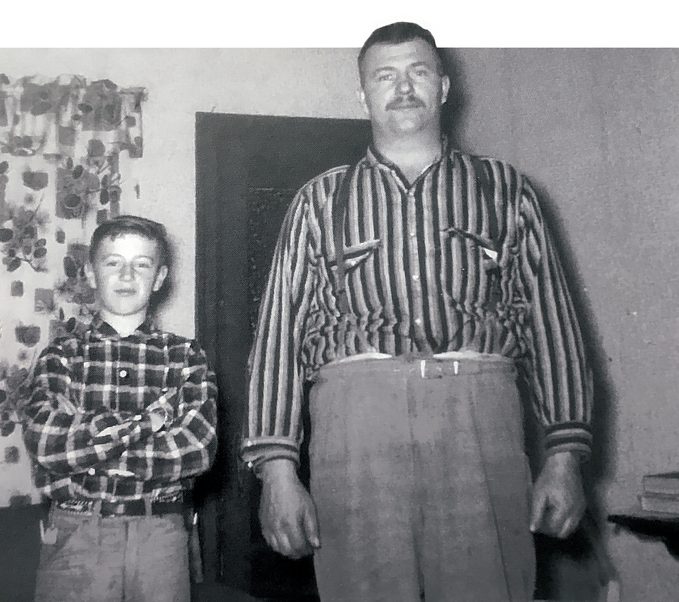

My dad was my hero. At six foot three and 285 pounds, he was a giant of a man. He was also immensely strong: he could lift a 45-gallon, 500-pound barrel of diesel fuel onto a truck. On one occasion, he lifted a reticent 600-pound steer onto a stone boat. When I was in grade school, none of my buddies ever said, “My dad is tougher than your dad.”

When God made my dad, he threw away the mould. There was no one like him. And my dad was smart—brilliant, actually. Despite the fact that he had only a rudimentary elementary school education, he was a first-class blacksmith, pressure welder and journeyman. He was highly educated in his line of work. If it was made of iron, he could fix it or make a new one.

Typically, Dad began his day at 4 a.m. with breakfast. While my mother and we kids were sleeping, Dad was loading up on extremely high-calorie, cholesterol-laden food—slabs of bacon with six eggs swimming in the fat, and bread with thick butter, all washed down with steaming mugs of black coffee. Then, by 5 a.m., it was off to the shop.

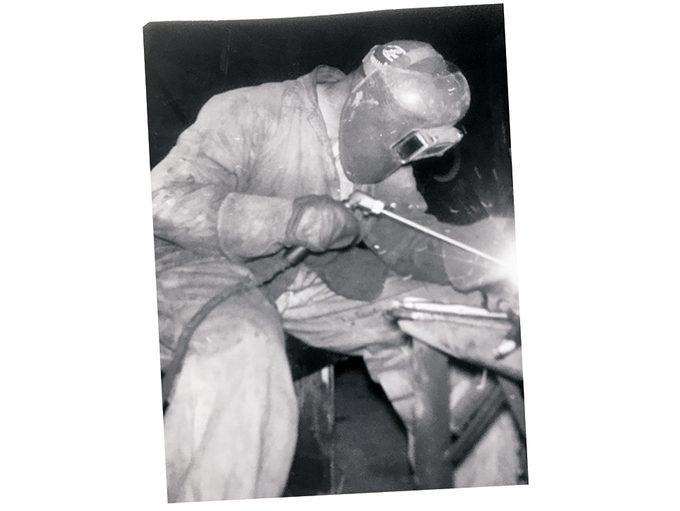

Blacksmith work came first. Rows of farmers’ cultivator sweeps awaited. First, Dad would build a coal fire in the forge. When the embers were glowing-hot, he’d place four cultivator sweeps on the coals. Then, when they were red-hot, he’d move them aside and put four more in the fire. He’d flatten out the edges of the first four, one at a time, with hammer on anvil. Then he’d temper them in a water trough.

Ploughshares were a different story. Typically, six inches of the worn-down front point had to be removed with a cutting torch and a new factory-made point welded on. The ploughshare was then heated in the forge and shaped with a trip hammer (a mechanical device operated with a foot pedal) and blacksmith hammer, then tempered in a water trough. Heavy coulter ploughshares were the most difficult to repair: A strip of grader blade had to be welded onto the instrument’s cutting edge, heated in the forge, then pounded, flattened and shaped with the trip hammer and, finally, tempered. It was extremely hot work. Dad drank a gallon of water at a time. In summer, you could see streaks of salt on his coveralls.

All work and some play

Around 9 a.m., Dad’s blacksmith work was done for the day, so it was time to turn his attention to constructing stock tanks and repairing various items of machinery. He also worked on cars: One vehicle after another was put up on the hoist, then he installed shocks and mufflers, welded frames and gas tanks, soldered radiators and did oil changes.

How competent a welder was Dad? He had no peer—no equal. A good example was how he’d remove a broken manifold stud. First, he would place a small piece of pipe over the stud and weld from inside the pipe until he reached the top. Next, he would weld a nut to the top, heat up the surrounding metal with a cutting torch and turn the broken stud out. No one else could do that.

Another of Dad’s specialties was repairing vehicle gas tanks. There wasn’t a lot of pavement north of Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan, where we lived, so gas tanks got pretty beat up. Dad would remove the tank and, so it wouldn’t blow up, run an exhaust hose from a gas-driven welder or half-ton truck into it for a half-hour. Then he would shape a piece of 20-gauge sheet metal over the hole, hammer it to fit the contour of the tank and weld the perimeter with an oxyacetylene torch. On one occasion, when the truck ran out of gas, the tank blew just enough to smooth out all of its wrinkles and dents. It looked like a new gas tank. The customer was amazed.

Dad was a kind and generous man. He would lend money to down-and-out people, with no hope of ever being paid back. His other great love was gardening. His half-acre garden behind the shop yielded more than the family could hope to use. So folks, including people Dad didn’t even know, were free to help themselves to his produce—as much as they wanted.

Dad was not a religious man, except for a short while on Sunday mornings. He would be stirring dark, ground whole wheat pancake mix with his huge baseball mitt-sized hands while singing religious songs in his deep bass voice, accompanying Pat Boone and others singing “How Great Thou Art.” When the morning’s LP was over, religion was over for the week, until the next Sunday.

Incidentally about his pancakes: Everybody, including the grandchildren, was expected to have one and then say something along the lines of, “Grandpa, are these pancakes ever good!”—even though they weren’t.

Dad usually finished off his week by stopping by the Empire for a drink before coming home. Invariably, he was accosted by someone who wanted to “twist wrists with Wilf ”—the test of a strongman, and Dad was the person to beat. The bet was always for $20—and Dad always came home with an extra twenty in his pocket.

Next, read the heartwarming story of how one man reconnected with his father through email.