Behind the trails

Back in 1999, my partner Cindy and I lived on Calvert Island, B.C., for a time.

For centuries, the east side of the island has been used as a blockade by mariners for protection from the Pacific Ocean swells generated by the approximately 7,000-kilometre crossing from Japan. While exploring the rugged west side of Calvert, we discovered overgrown paths lined with plastic debris tied to tree branches, which were used as trail markers by boaters.

The 10-foot salal bushes were so thick, we had to crawl on our hands and knees to make it to the next opening. After spending two winters hacking out paths, and erecting boardwalks, bridges and ladders, we found out that there was a much more interesting history to these trails and beaches than we initially knew.

Back in time

Following the Japanese attack on the U.S. Aleutian Islands in Alaska in June 1942, the U.S., along with additional aid from Canada, sent military personnel to Alaska to help with the battle of the Aleutian Islands.

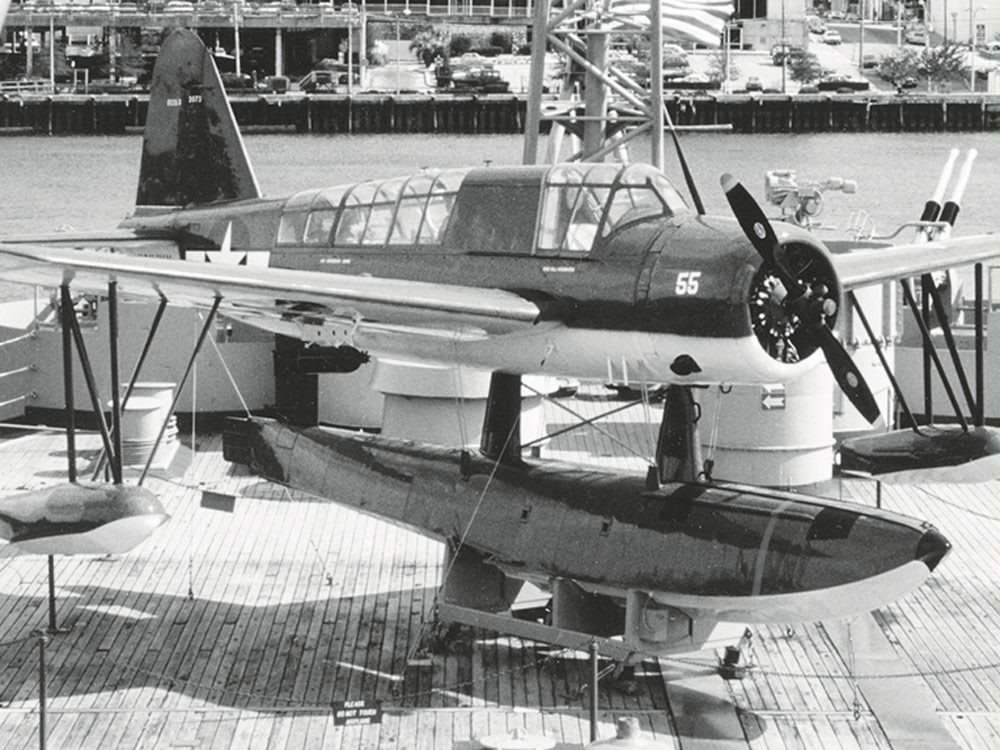

Fast forward a couple of months to August 1, 1942. At the Floyd Bennett Naval Air Station in Brooklyn, N.Y., pilots Ensign Mac J. Roebuck, Ensign Jack Sanderson and Lt. Ray G. Thorpe received their new OS2U Kingfisher aircrafts; it took seven days to fly across the U.S., toward Hawaii, their initial destination. When the squadron landed at Sand Point Naval Air Station just north of Seattle, however, their fixed landing gear was exchanged for floats, and they received new orders, sending the squadron to Kodiak, Alaska, instead.

Two weeks later, the squadron left Sand Point Air Base and crossed into Canada. Flying north over Vancouver Island, bad weather forced them to land at RCAF Station Coal Harbour. The following day, they left for Ketchikan, Alaska, heading north. When the planes became engulfed in dense fog, they were separated. Ensign Mac Roebuck, who was fresh out of cadet class with about 100 hours of flight time, crashed his plane into Mt. Buxton on Calvert Island. The impact tore off the right wing and did extensive damage to the main float. He and his navigator, Stanley Goddard, were uninjured.

Using the planes’s compass, Roebuck and Goddard hiked down Mt. Buxton in a westerly direction until they reached the shoreline. The fog was so thick they couldn’t see more than five feet in front of them, so they used a rope as a lifeline, keeping them together for two-thirds of the way down the mountain to avoid getting separated. Hearing a plane overhead, they built a signal fire using the wet wood found on the beach. They were able to communicate via Morse code, using a flashlight and signal lamp, and nearby RCAF Station Bella Bella was contacted to assist in the rescue.

Discover the fascinating story of the Farmerettes—Canada’s forgotten wartime heroes.

Left behind

Ensign Mac Roebuck stayed behind on Calvert Island, and, along with six Royal Canadian Air Force men from RCAF Station Bella Bella, camped in a tent on the beach for two weeks. The salvage crew made eight trips up Mt. Buxton to the crash site, dismantling parts of the plane, and then proceeded to pack the machine gun, instrument panel and radio on their backs, for transport down the mountain to the beach. The engine was put on the torn-off wing and pulled down the mountain until the bush got too thick; they then dismantled the engine and carried it the rest of the way to the shoreline. The salvaged parts were transferred to the United States.

Ensign Mac Roebuck returned to his squadron in the Aleutian Islands and the remains of the OS2U Kingfisher were left on Mt. Buxton for another 22 years.

Find out how a metal shaving kit saved this Canadian soldier’s life in WWII.

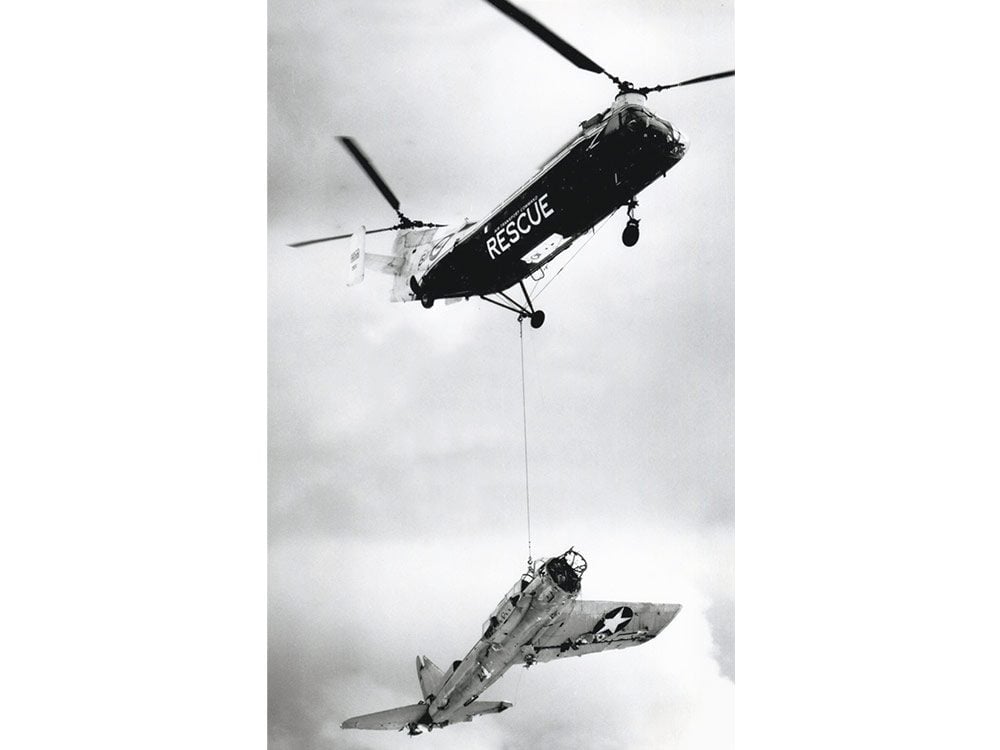

The rescue

In 1964, the Canadian Minister of National Defence thought it would be a good training mission for the Vancouver-based Sea Island Search and Rescue 121 Composite Unit to salvage the aircraft. In March of that year, authorization was given to airlift the Kingfisher off Mt. Buxton using a helicopter. This was not a simple task since the plane was covered with two feet of snow. The wreckage was airlifted to Port Hardy, Vancouver Island, where the Kingfisher had left from on August 20, 1942, for what turned out to be its last flight.

Restoring the Kingfisher

The pieces of the plane were transferred to the Air Force Museum in Calgary for restoration. After years of negotiations with the Naval Historical Center in the United States, the OS2U Kingfisher was turned over to the North Carolina Battleship Commission. In the spring of 1969, the aircraft was shipped from Calgary to Wilmington, North Carolina. It took about a year to complete the restoration. On June 25, 1971, the OS2U was dedicated aboard the battleship North Carolina, and today, remains a monument on that battleship.

The Kingfisher’s legacy

Every year, thousands of visitors come to Calvert Island by boat, plane and kayak to walk the chain of trails leading to 12 remote white-sand beaches, most not knowing what happened here in August 1942. Hopefully, this story will change that.

I like to think in a very small way that Cindy and I have been a part of this historical event, bringing people together to re-live a part of Canada’s involvement in the Second World War, on the west coast of British Columbia.

Next, check out these true stories of Canadians who helped make D-Day a success.