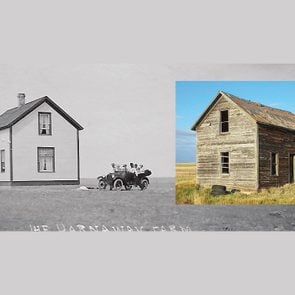

An Essay I Wrote During the Great Depression is a Time Capsule of Small-Town Prairie Life

Despite the tough economic times, life was rich in the friendly Prairie village of Blumenort.

Growing up in Canada during the Great Depression was grim in many ways, but when, at 17 years of age, I looked back at my childhood it seemed idyllic even though we had no phone, running water or electricity. High schools and jobs were far away, so we had to leave our familiar village. I wrote this essay when I was homesick in my dormitory room at Rosthem Junior College:

Beautiful Blumenort

The friendly village of Blumenort in which I was born, is located in southern Saskatchewan. Lying just east of the No. 4 highway, it is right in the centre of a fertile farm area. Twenty-one brown frame homes occupied by 21 families stand on either side of the road running east and west. Each home is built on a yard-lot of similar size, and is joined to the next by a common fence. Around this group of homes is the community pasture and beyond stretch acres and acres of golden grain.

As you come along the highway and approach Blumenort at dawn you will hear the tinkle of a bell and the trampling of cattle hooves. The village herdsboy is just rounding up cattle and will take them to the community pasture. As soon as the bell is heard, each villager opens the gate and lets his cattle join in the general concourse of beasts.

Unique architecture is employed in the construction of the cozy homes. The house, pump-shed, barn, garage and granary are all harboured under one roof. At one end of the structure are the rooms used by the family. A hall usually used also as a pump house separates this from the barn. On the one side are several stalls for the cattle and beside this is a shed called the “oven side” used for storing chop and bags of sunflower seeds. Along the other end of the building is the granary and above this is the hayloft.

The church, the centre of community life, is situated in the middle of the village, opposite Flowerville School. All are welcome to worship here. When the harvesting is finished, ladies bake a cake, some buns, and roast fowl for the Thanksgiving Festival. Very few people are absent at this occasion because it gives them an opportunity for meeting not only people from our village but also from other nearby villages that have been cordially invited. Hopefully every one forgets his own needs with the result that the collection plate will groan under its weight.

The best of the harvest is exhibited in the food that is provided. An ample supply of provisions is on hand. As soon as one lady notices that there are only a few golden buns left, she calls Johnnie to her side. She whispers something to him and he dashes off towards home. In the blink of an eye he is back with a pail full of buns that she had put away in the pantry to be ready just in case they should be needed. Families bring a variety of tasty food and pickles cooked from the choicest vegetables. After having a delicious brown drumstick, each visitor receives a slice of cake topped with frothy icing. When all appetites have been satisfied, the villagers divide the remaining delicacies and happily return home.

As soon as snowflakes appear on the ground we begin to wonder whether it isn’t time for the pig butchering bees. One morning on our way to school we notice the men are gathered in little groups near the Funk, Friesen and Schmidt gates discussing the weight of the hogs. Now we are sure that there will soon be fresh spare-ribs. Typical Prairie cooperation is shown at this time. Friends help each other on that long and tiring meat-preparation day. The hams are salted, smoked and hung in a granary, while the lard pails are stored in the attic.

Because there are quite a few young people living so close together they can conveniently gather for sports all year round. A glassy ice-rink is constructed in Mr. Koop’s yard.

Keeping this rink in perfect condition provided a pastime for husky young fellows who have completed school. The dense shelterbelt around the schoolyard attracts huge drifts of snow. These drifts are sculpted into an excellent slide that gives pleasure to youngsters from December to March. In springtime the young people gather in the schoolyard to play softball and enjoy wiener roasts on warm June nights.

During the long, cold winter months social life continues in two Dutch dialects. The short paths leading from house to house are often traced by jovial neighbours. The men, usually dressed in overalls, are invited into the living room to discuss the prices of grain and the varieties of gopher poison. Women gather around the kitchen table to practice new embroidery stitches.

Whenever Death comes to visit the sunny vale, neighbours try to share the grief. The yard of the deceased is cleared of refuse and raked in preparation for the funeral. Two nights before the funeral almost every woman in the village sends her little Peter to the afflicted home with a pound of butter and a pail of milk for mixing bun batter. The following morning a man drives from home to home delivering a large lump of dough which will be baked into tiny buns for the meal at tomorrow’s funeral. Chairs and tables are also collected from homes to provide seating for guests at the funeral luncheon.

A minister clad in a long black jacket, black shirt, and high black boots speaks at this solemn occasion. He slowly reads a sermon. A few pauses are made in which the audience can reflect on its own past and sympathize with the mourners. When the body has been buried in the graveyard, which is located in the centre of the common pasture, the funeral guests return to share a meal.

A friendly relationship exists between neighbours in our little village. When unexpected company arrives at Mrs. Enns’s place, she doesn’t hesitate in going over to ask Annie Dyck to come and help her. Mrs. Gunther has a knack of baking peppernuts but she can’t tum out edible Easter bread. Her neighbour is an expert along this line, so they exchange delicacies. This exchange of goods is also of economic value. Lena and Tena carry the Free Press and the Courier across the street and exchange them so that their parents benefit from two papers and only pay for one.

The village of my childhood was surrounded by open stretches of Prairie that go as far as the eye can see. However, inside the small community the people are linked by a persistent spirit of caring for each other. In times of illness, fire or death, willing hands and sympathetic hearts reach out to help. Will people treat you as well anywhere else?

Later Life

Those were my anxious teenage thoughts when a letter from home told me of my parents’ planned move to the warmer West Coast. Because my parents moved to Matsqui, British Columbia, in 1948, I did not come back to Blumenort. Instead, I went to help them clean up after the Fraser River flooded our new home that spring. So it was necessary for me to quickly become independent, and teaching was the shortest route. Marriage, family and farming followed.

Finally, ten years ago we visited Blumenort and found it had kept up with the times and is a friendly, modern hamlet. And now as a senior, I have happily lived more than two decades in an open-spaced townhouse community called Glen View Meadows. It reminds me of Blumenort because the people are good and caring, just like the folks we had in our Prairie village.

Next, find out what laundry day was like in the 1930s.