The Revival of the Red River Cart

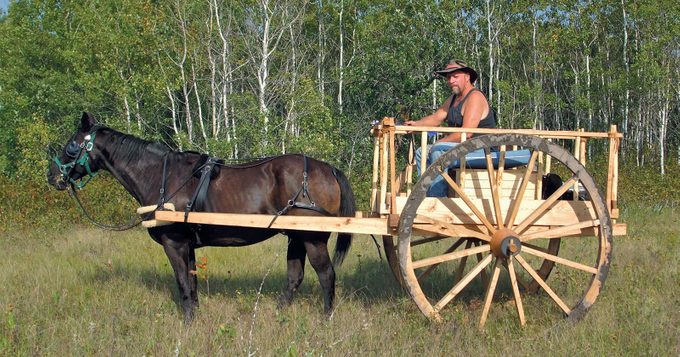

Once relegated to history, these sturdy transportation vehicles are finding new life thanks to two master crafters.

Ever since he was a young boy growing up in Roblin, Manitoba, Armand Jerome has been intrigued by the history and construction of the traditional Métis Red River cart. His father, Leon, had mentioned how their family had used the Red River cart in the old days, which seemed to quench the young man’s curiosity—that is, until around the year 2000, when Armand joined the newly formed Métis Council Local in his new home of St. Norbert, Winnipeg. There, he met an executive, Don Benoit, and the two became fast friends. At weekly breakfasts, they would discuss world issues, including the plight of the Métis Nation and their struggle to achieve proper recognition and be given the rights due to them. Don often spoke of gathering a crew to build canoes and Red River carts to showcase Métis culture. But due to health problems, he didn’t live to see those goals realized.

In 2001, Armand was chatting with a friend about the North American Indigenous Games that were to be held the following year in Winnipeg. The two thought it would be nice to see a few Red River carts involved in the opening ceremonies. This gave Armand the incentive to follow through on his dream of making carts and driving them. He gathered a crew together from the Métis Local to start researching cart construction.

Building Red River carts was a trade long forgotten; in fact, some of the “blueprints” were merely various personal impressions and recollections of the vehicles. The team lacked historical information about cart building. And although Armand’s crew had the help of someone who’d built carts before, even that man was not sure how they’d hold up in practical use.

As the team built their first four carts, they worked alongside local horse owners to design the most efficient and stable way to hook the wagons up to the animals so as to ensure the carts would be usable.

Once they were built and the crew had experimented with harnessing, the men began to work with their local Trans Canada Trail group on the prospect of driving the carts along portions of the Crow Wing Trail. This path closely follows an original route that Red River cart drivers would travel in the 1800s to transport goods to and from the Red River Settlement, as well as the Crow Wing Settlement on the Mississippi River. The team’s goal was to drive the carts and arrive in Winnipeg in time for the Indigenous Games. Armand recalls that the design of these early-attempt carts was quite inferior to the historical versions, and that they required piecing together every evening just to make another day of use on the trail. Some days, only a couple of carts were used while the others were being repaired. Still, after a gruelling week on the trail, the team made it to the games.

That voyage begat an era of 20-plus years of Red River-cart research and heritage journeys across Manitoba and Saskatchewan, logging more than 3,000 miles on the wagons. Armand’s most outstanding expedition was dubbed “The 800 Miles to Batoche,” during which he travelled the Carlton and Trans Canada trails from St. Norbert to Batoche, Saskatchewan, joined in celebration along the way by various Métis and other groups.

Throughout his treks, Armand remained true to his dream of creating an authentic, historical Red River cart by trial and error, using only the tools and research at hand. In 2008, he was joined by his future wife, Kelly, who’s since worked side by side with him to make this dream a reality. In 2009, they launched Jerome Cartworks, which Armand says produces carts that are as close to the originals as can be made.

The units are built with local hardwood such as oak—which Armand considers the most functional of the woods—and ash. These were also used in 1800s-era cart construction, as they were indigenous to the Red River Valley and plentiful enough that materials for repairs were available along the trail as needed. The carts’ hubs are made from elm due to this wood’s resistance to cracking. And the basket spindles are made from willow or birchwood, which are harvested in winter only.

It takes a minimum of 200 hours to construct one cart, not counting the time and effort required to gather the various woods and materials. Factoring in wood prep such as bark peeling, planing, dyeing and finishing, the entire build, from beginning to end, is closer to 300 to 400 hours of work.

No metal parts—such as metal bands on the wheels, or even metal screws and nails—are used in the carts. Instead, dowels hold everything together. Due to this all wood composition, the carts are able to float across rivers, though they lack the buoyancy to carry loads across water. To accomplish this, a driver would have to cut a couple of logs, strap the cart wheels on top of the logs, and then strap the cart itself on top of the wheels, essentially converting the wagon into a temporary raft.

Jerome Cartworks, based near Oakbank, Manitoba, has so far created more than 45 carts, which have mostly been used in parades and ceremonies across Canada, including at Métis Locals and RCMP headquarters.

Next, check out 20 unique artifacts you’ll find in Canadian museums.